Abstract

This insight constructs and critiques a genealogy of Yiddish Digital Humanities through a critical analysis of the labelling practices of Stutchkoff and Weinreich’s Yiddish thesaurus, ‘Der oytser fun der yidisher shprakh’ (1950). Following Zaritt , ‘Taytsh labeling’ and ‘Taytsh Digital Humanities’ are introduced as alternative methodological concepts, helpful for constructing a non-normativising Yiddish Digital Humanities.

Geneology

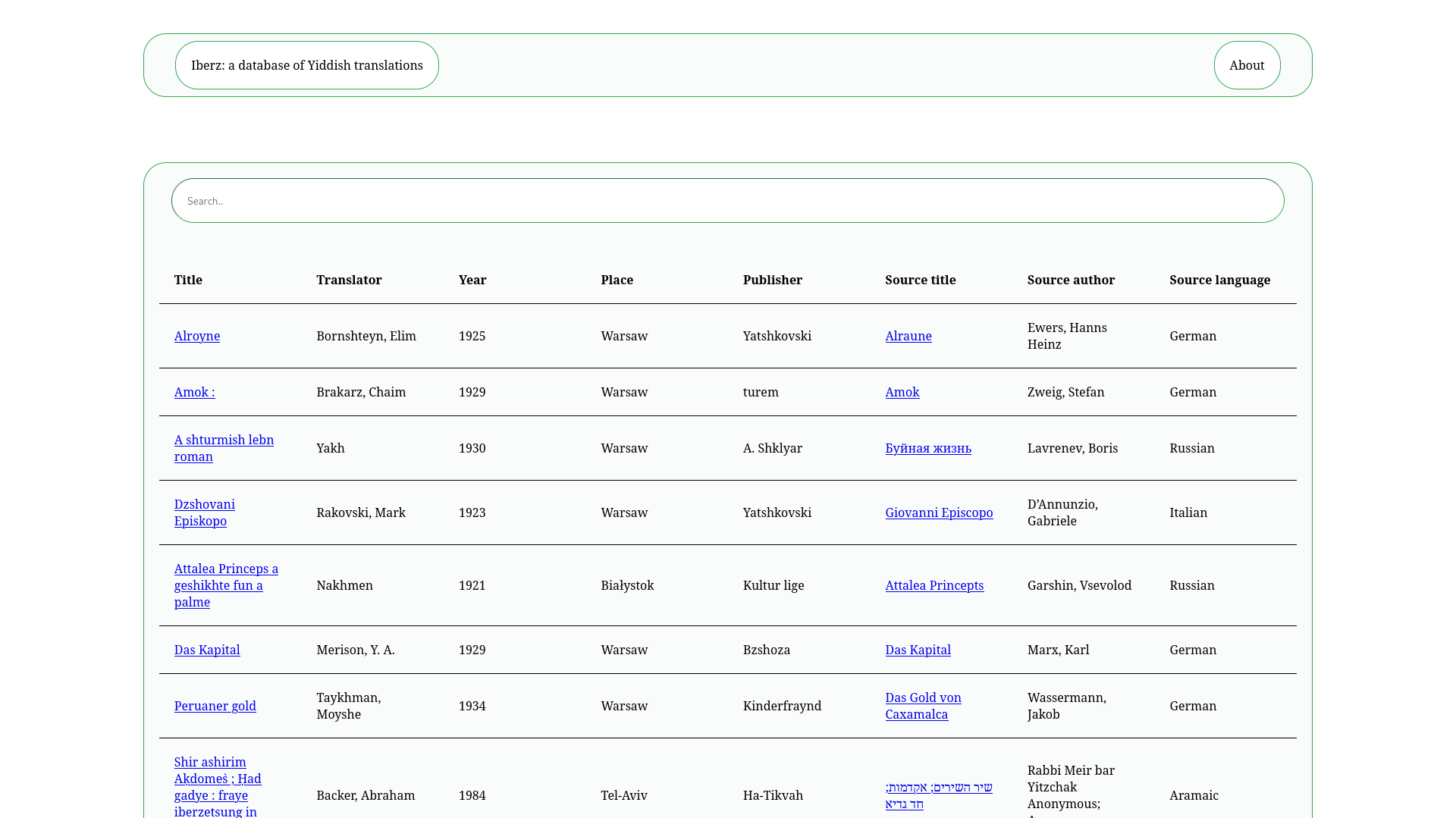

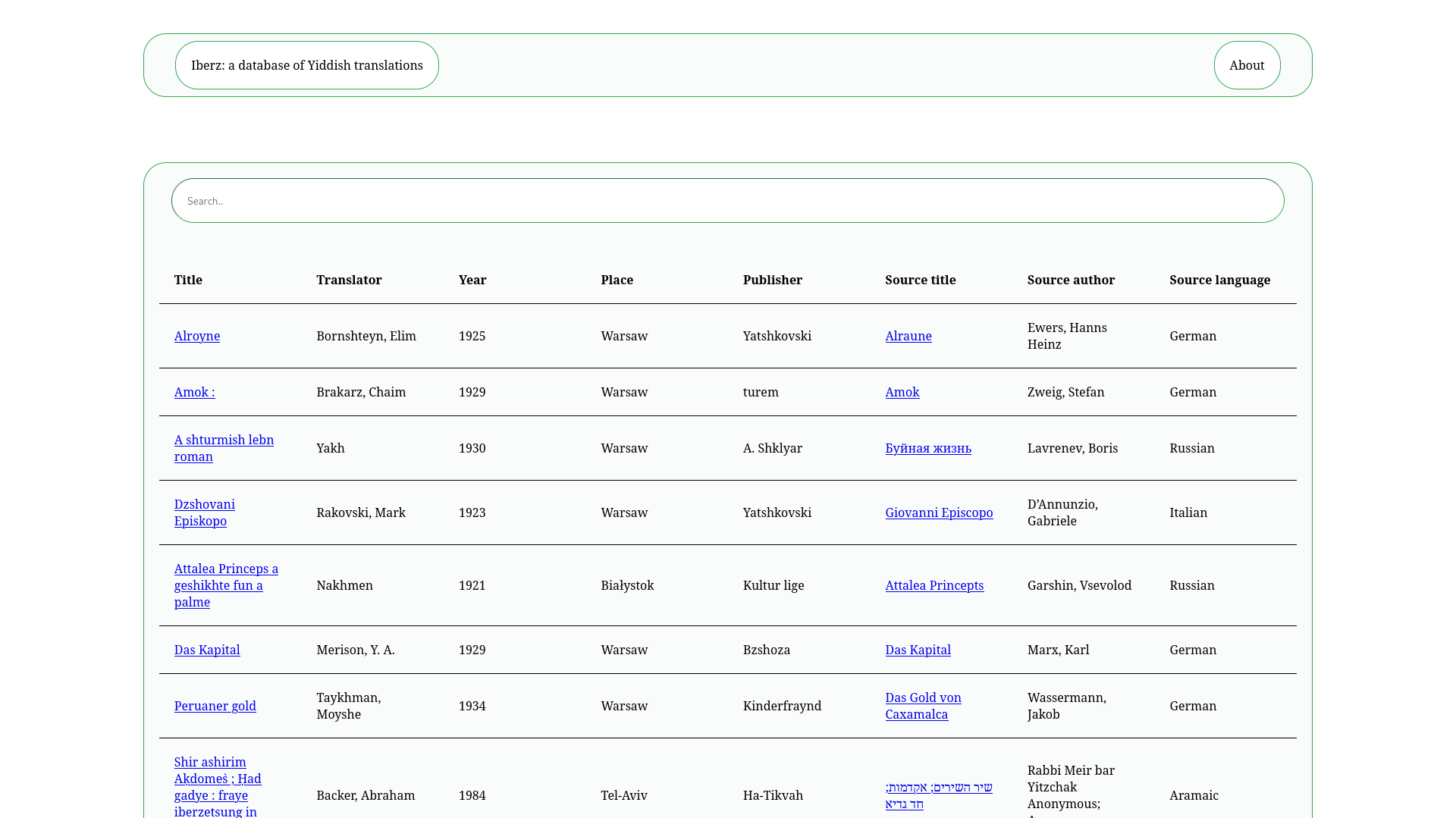

When considering Yiddish digital humanities, it becomes clear that there is much to do. We can list current Yiddish digital humanities projects like dybbuk.co, shund.org, the burgeoning Yiddish drama corpus on dracor.org, and my own humble iberz.org—but how can we construct a Yiddish genealogy? Who are our predecessors? The pioneering work of Refoyl Finkl, who has been producing digital Yiddish resources for decades, is noteworthy; but beyond this, it seems we are floating in a vacuum (, ‘Yiddish and Hebrew Texts’).

But if we broaden our scope to encompass not only the Digital Humanities (DH), but also data-driven and analogue approaches to Yiddish culture more broadly, a clearer genealogy emerges. On the one hand, we have the ethnographic work of Ansky and Ruth Rubin, who collected Jewish folkways and folksongs respectively (see ; ). There is also the pioneering work of Avrom Kotik, who, at the beginning of the twentieth century, employed surveys and data from lending libraries to analyse the reading habits of Yiddish readers . But perhaps the most important predecessor is the Yiddish lexicographical tradition, represented most iconically by Nachum Stutchkoff and his wonderful אוצר פֿון דער ייִדישער שפּראַך (Oytser fun der Yidisher Shprakh, ‘Treasury/thesaurus of the Yiddish language’; see ). If DH is a data-driven philology, then this lexicographical heritage is a good place to look for its origins in the Yiddish world.

Stutchkoff was born in 1893, in Russian Poland. He was raised in a conservative, religious milieu, but began to study secular texts in secret (Birnboym, ‘Stutshkov, Nokhum’). Eventually, he became involved in the Yiddish theatre scene surrounding Y. L. Peretz, where he both acted in and adapted a number of plays for the Yiddish stage. In 1923, he immigrated to America, where he continued his theatrical activity, eventually writing drama for the radio and jingles advertising matzo. It was here that he also began work as a lexicographer, publishing in 1931 the ייִדישער גראַמען־לעקסיקאָן (Yidisher gramen-leksikon), a rhyming dictionary of about 330 pages, perhaps compiled to aid him in his songwriting (Stutchkoff, Yidisher gramen-leksikon).

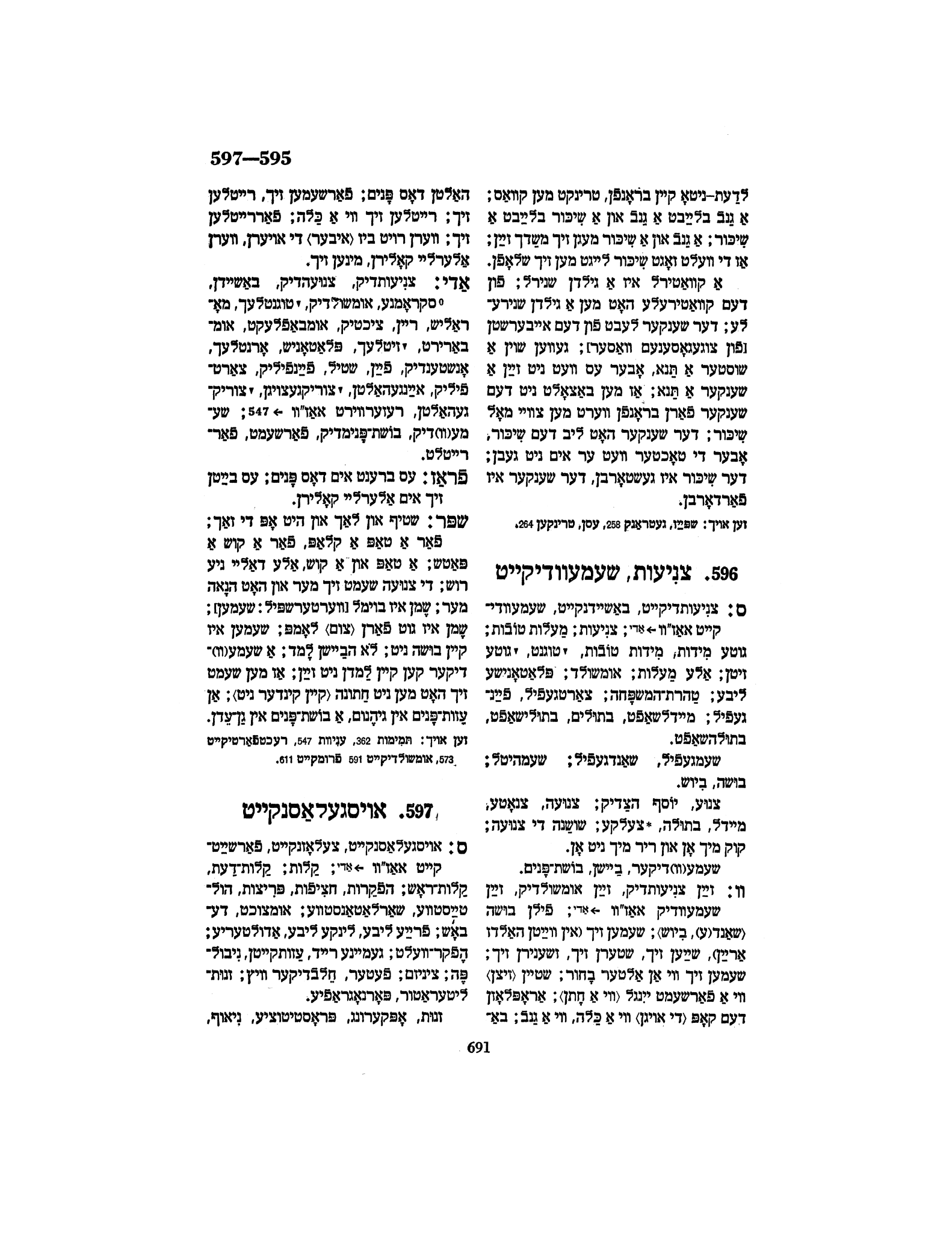

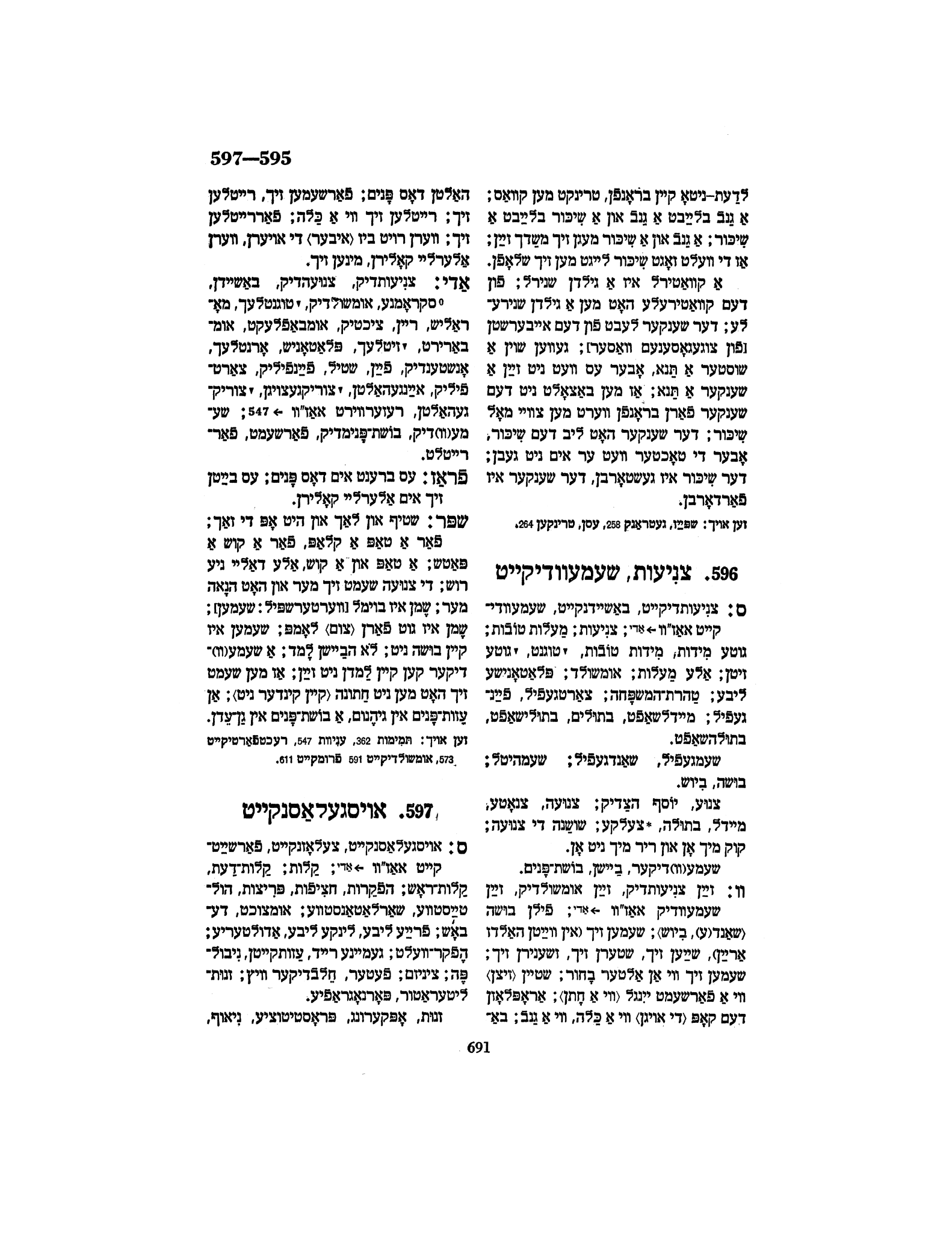

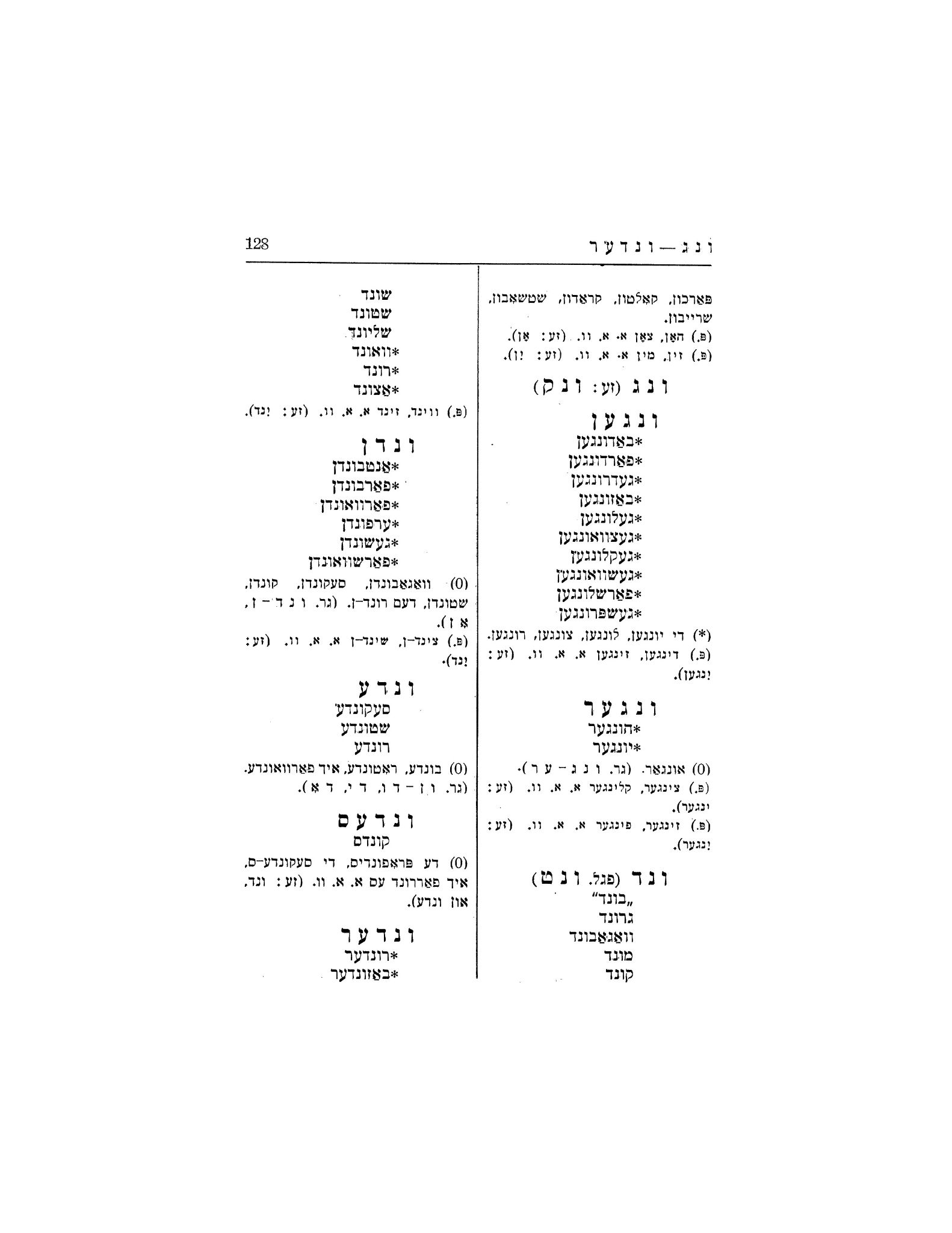

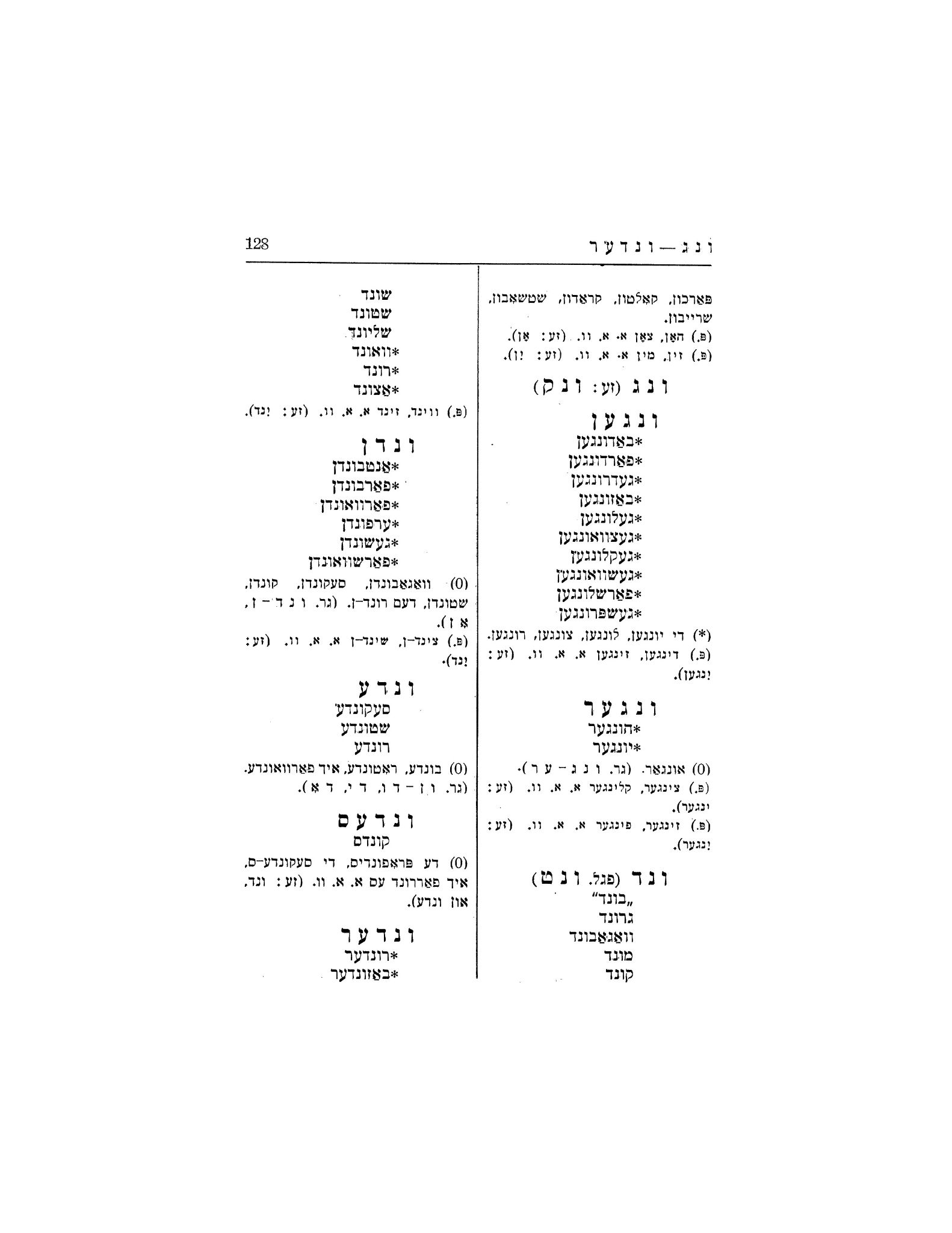

However, Peretz is best remembered for the aforementioned Oytser, published in 1950 and edited by the Yiddish linguist Max Weinreich. It is a colossal work, about 930 quarto pages, including the index. The thesaurus is organised by 620 semantic fields from ‘זײַן’ (zayn, ‘being’) to ‘(געבעטהױז (ניט ייִדיש’ (gebethoyz (nit yidish), ‘prayer house (not jewish)’). Within each field, words are systematically organised into fields of nouns, verbs, and adjectives. In some cases, words are followed by an arrow pointing to a number, indicating a related semantic field.

The Oytser is not only a monumental work of Yiddish lexicography; it also served as a prescriptive work, an attempt at language maintenance. Its objective was to produce and defend a particular register of Yiddish, which the editors call kulturshprakh. There are many words which the editors included for posterity’s sake, but whose use was proscribed with a variety of symbols and formulae: ↓ (not recommended in the kulturshprakh), ° (not (yet) accepted in the kulturshprakh), * (vulgar expression), as well as a number of acronyms denoting proscribed origins (e.g. [אמ] for Americanisms, [קל] for Klezmer-loshn). In the case of Germanisms, Weinreich explained that they were retained in the Oytser primarily to prevent the misconception that these words had been forgotten, secondly in order to caution against them . In contrast, the editors adopted a more liberal attitude toward Slavicisms, which are often marked with °, an assertion that they could potentially be accepted in the kulturshprakh. This leniency was a response to the decimation of Jewish communities in Slavic regions during the Holocaust; Slavicisms should be preserved, it was felt, in order to enrich Yiddish, and, more implicitly, as a memorial to a cultural contact that had been severed. Weinreich remarked that, before the Holocaust, their attitude towards Slavicisms was much more stringent .

The editors’ attitude towards Americanisms is notably different: American English was, at that time, exerting an inexorable influence on American Yiddish, and Weinreich argued that the kulturshprakh must avoid these usages, lest it be ‘flooded’ with Americanisms . These attitudes reflect the foundation of contemporary Yiddish prescriptivism, which considers Slavic loans as an integral, “authentic” part of the Yiddish language, while proscribing German and English borrowings.

Lehavdl labelling

To conceptualise Stutchkoff and Weinreich’s practice of including then stigmatising proscribed lemmas, I invoke the Jewish exclamation lehavdl (להבדיל), which literally means ‘to separate’. This is the same verb that is used in Genesis 1:4 to describe God separating the light from the darkness. In Jewish speech, this is an exclamation, which, according to the Comprehensive Yiddish Dictionary, means ‘not forgetting the difference (between sacred and profane things mentioned successively), excuse the comparison’. According to this dictionary, the phrase can be exemplified by the sentence אַ מענטש און להבֿדיל אַ מאַלפּע (a mentsh un lehavdl a malpe), which they gloss as ‘a man and a monkey, excuse the comparison’. In order to make it palatable that man, a sacred animal, and monkey, a profane animal, are mentioned in the same breath, this difference must be acknowledged, and this is the purpose of lehavdl.

Another example can be taken from Samuel Leib Zitron’s description of how Shomer adapted Russian and German popular novels for Yiddish audiences:

[ער] האָט אומגעביטען פּאַריז אױף הײדוטשיסאָק און בערלין אױף באַלטערמאַנץ וכדומה, האָט אָנגערופן די העלדן מיט יידישע נעמען; אַ גלח איז געװאָרן, להבדיל, אַ רב, מיט פּאות געװײנליך, פון אַ קלױסטער איז געװאָרן, להבדיל, אַ בית־המדרש…

[(He) changed Paris to Adutiškis and Berlin to Butrimonys and so on, and gave the heroes Jewish names: a priest became, forgive the comparison (lehavdl), a rabbi, with payes of course, and a church became, forgive the comparison (lehavdl), a Jewish study house].1Heydutshisok and Baltermants are Yiddish names for Adutiškis and Butrimonys in Lithuania.

Here, Shomer’s adaptation, or at least the description of it, requires lehavdls because it imagines a possible continuity between the sacredness of the Jewish religion, and the profane, pseudosacredness of Christianity. The lehavdl serves to emphasise the impossibility of such a continuity, even whilst the author describes it.2It is worth noting that the germanising language of Shomer’s novels, despite the judaising mentioned above, would certainly not be considered kulturshprakh.

Stutchkoff and Weinreich practise a form of lehavdl labelling: the superstitious marking of undesirable words to prevent them from being conflated with the “real”, “good” Yiddish, meaning the kulturshprakh, however that might be defined. By doing so, they take the reality of spoken and written Yiddish, with all its supposed impurities, and process it to make it comply with their vision of the language. As the reader might infer, I am opposed to such an attitude towards Yiddish. A doctrine of purity is untenable for any language, let alone one as mixed as Yiddish.

Nonetheless, this lehavdl labelling yields a considerable amount of useful data. As much as I am opposed to the ideology underpinning their choices, I appreciate that the editors decided to enrich the data with their unsavoury prescriptivism. Their labelling practices enable us to identify those words which were prevalent in Yiddish in the first half of the twentieth century but were proscribed by proponents of kulturshprakh (or by Stutchkoff and Weinreich, at least). More generally, this practice provides etymological indications which would otherwise not be preserved.

Yiddish

The stance of Weinreich and Stutchkoff is endemic to the sort of normative Yiddish culture that emerged at the end of the nineteenth century, which sought to produce a Yiddish linguistic and literary culture that was autonomous, “pure”, and operating on the same level as European literatures—not dependent upon them. Many of the ideas which were central to this concept of the Yiddish language and literature were first developed in Germany, in the writings of nationalist philologists like Herder and the Brothers Grimm. These ideas had developed in Jewish culture during the haskala (Jewish Enlightenment), and their formulae (that language determines and is determined by culture; that language and culture must therefore be “pure”), once resolved, usually culminated in the assertion that Hebrew was the pure, authentic language of the Jewish people, while vernaculars that were regarded as impure should be discarded.

At the end of the eighteenth century, when enlightened Jews like Mendelssohn began to introduce these ideas into the Jewish culture, and throughout the first part of the nineteenth century, there were many names for Yiddish. The most popular, perhaps, were זשאַרגאָן (zhargon, ‘jargon’) and עברי־טײַטש (ivri-taytsh, ‘Hebrew-German’ or ‘Hebrew-interpretation’). At this time, Yiddish was not conceived of as a language in the same sense as Hebrew or German; it was spoken vernacular but, as far as they were concerned, it was not quite a language.

To demonstrate what I mean, I refer to the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of language, which even today reflects some of the same concerns that guided maskilic and post-maskilic Jewish-language ideologues:

[A language is] the system of spoken or written communication used by a particular country, people, community, etc., typically consisting of words used within a regular grammatical and syntactic structure.

The challenges facing Yiddish included its perceived lack of a “system” (because its lexicon and grammar were so unstandardised) and its insufficient “particularity” (because of its mutual intelligibility with German, and its incorporation of Slavic and Semitic elements).

Yiddish, as we know it, was born of a reaction against the idea that only Hebrew could be the national language of the people. And yet, although Yiddish activists rejected the supremacy of the Hebrew language, they did not necessarily reject the ideologies that had elevated it to this position. Instead, these ideologies were reconfigured to identify Yiddish as the essential Jewish language, instead of Hebrew. The popularity of the term Yiddish (which means “Jewish”) is closely tied to movements aimed at transforming zhargon and ivri-taytsh into a respectable, standardised language (see ). It was to be a national language of the Jewish people, as the Czernowitzer conference of 1908 declared, and therefore it would be called Yiddish, the Jewish language. This name, and the claims that accompanied it, would ensure that Yiddish was sufficiently particular to the Jewish people—grammarians, orthographers, and lexicographers (like Stutchkoff) would take care of its systemic integrity.

Taytsh

A recent article by Saul Zaritt argued that in order to understand what Yiddish is and what Yiddish does, we must return to an understanding of Yiddish as taytsh . Taytsh is a useful term because of its polysemy: it means both ‘interpretation’ and ‘German’ (by way of comparison, consider the German deutsch and deuten). It is an ambiguous term, and it stakes a very different claim than “Yiddish”. The term “Yiddish” foregrounds the language’s status as a carrier of national identity—the Jewish language—whereas “taytsh” places the emphasis on its reverse aspect: the German vernacular of Ashkenazi Jewry. Taytsh does not assert claims of linguistic purity or national solidity . It is not interested in national purity. As Zaritt stated:

Taytsh is an untranslatable vernacular of translation, a Jewish language that describes the boundary where Jewishness begins to fall away, though never disappears. That it is also now (and perhaps always has been) a dying and undead language, a forgotten language that every-one knows, only heightens its translationality. Taytsh does not begin to imagine the possibility of self-possession, at least not yet. Taytsh is not entirely one’s own, it is not of one’s blood or tied to divine birthright. It is a language of migration that begins and ends elsewhere, a language of improper hospitality, a language of translation.

The project of Weinreich and Stutchkoff, the Oytser, is a Yiddish project and not a taytsh project. It seeks to affirm and protect Jewish national identity by maintaining the Yiddish language. Though their scholarly rigour compels them to include proscribed terms in the Oytser, these terms are clearly marked and separated from the unmarked corpus of “acceptable” Yiddish. These marks, as expressed above, function as lehavdils—compulsive utterances, spoken to disarm blasphemous comparison.

Therefore, if the Oytser is a forerunner to Yiddish DH, with all its obsessive prescriptivism, then how might we imagine taytsh DH? What does it mean to taytsh label, without lehavdils?Because of the history of taytsh, this is not very difficult to imagine. Taytsh originates from the verb taytshn, meaning the vernacular interpretation of the Jewish holy texts. Here, as always, both of taytsh’s inseparable definitions are at play: it refers to the interpretation of holy texts in the German vernacular. As Zaritt argued:

Taytshn refers to the pedagogical practice of word-for-word translation of the Pentateuch, in which the teacher of the heder (one form of traditional early Jewish education) instructs the youngest of Jewish pupils to render a Hebrew word into the Germanic register of Yiddish. The act of taytshn enables the encounter between the sacred and the profane, between a venerated literary language and the vernacular, and provides access to the holy text for the “everyday Jew”.

To taytsh, to produce taytsh, is thus to make the unknown knowable—to bring important, perhaps eternal documents into the profane world, with all of its contingencies, with all of its strange and fleeting demands.

We can use this definition of taytsh to understand Weinreich and Stutchkoff’s labelling practices. Labels are a form of taytsh insofar as they bring data into conversation with the world around us—they render data palpable, manipulable, and ergonomic. Though they might deny it, Weinreich and Stutchkoff were “taytshing” when they applied their labels: making their masses of lexicographic data serve their purposes by orienting it towards—and often against—the contingent world in which they lived. However, their objectives, in fact, directly opposed Zaritt’s account of taytsh: whereas taytsh seeks, in a sense, to make the sacred contingent, Stutchkoff and Weinreich sought to elevate the profane world of Yiddish, with all its contingent usages, into a sacred, inviolable language through their commentaries.

The difference between Yiddish DH and taytsh DH—between the labelling practices endemic to both—though the former is very young and the latter is hypothetical, is perhaps best understood as a matter of perspective. Yiddish labelling claims that the proscribed words in the Oytser are bad for Yiddish. To the Yiddish labeller, the purity and sanctity of Yiddish, and its status as a representative vernacular of an autonomous Jewish people are paramount. These perspectives will not be shared by the taytsh labeller or the taytsh digital humanist, neither of whom seek to proscribe with their labels, but rather to explain and interpret.

Hermeneutics

To understand labelling as taytshn has broader implications for the DH. For one, it sidesteps the occasional accusations of traditional literary scholars that computational literary studies is a positivist endeavour. To label, as to taytsh, as to translate; it is a hermeneutic act. It is vernacular interpretation, a way of reading a text and of bringing it into the fold. It does not exhaust the labeled text—it enriches the text. In this, I agree with Bode, who sees computational literary studies, like all literary studies, as a performative practice of ‘writing with writing’ , and Venuti, when he says that there is no semantic invariant to be revealed in translation .

There is an ongoing debate on the role of Hermeneutics in the DH, with Sibylle Krämer voicing significant opposition, warning that to hermeneuticise the DH ‘reinforces a traditional but problematic self-image of the Humanities’, which ‘hypostasizes interpretation and hermeneutics as key methodology of the Humanities’ .3For other approaches, see and .While I am sympathetic to her understanding of digital methods as participating in a productive cultural technique of flattening, and I do not believe hermeneutics to be the ultimate or sole framework for the humanities, given Yiddish’s long-standing, traditional hermeneutic function as taytsh, I see hermeneutics as a fruitful approach for theorising Yiddish/Taytsh DH, even in its current, underdeveloped form.

Conclusion

Although Stutchkoff and Weinreich’s labelling practices are in tension with Zaritt’s taytsh, to understand these practices as a form of taytsh allows us to reclaim them as useful data. I do not understand them as legitimate directives for how the Yiddish language should be, because I reject that premise; instead, I understand them as artefacts of a particular view of the Yiddish language, one with which I disagree. Nonetheless, these artefacts offer valuable insight into the Yiddish language as it existed and as it was imagined, around the year 1950. Weinreich and Stutchkoff produced useful taytsh, even without knowing it. I am grateful for their intervention, despite being somewhat at cross-purposes with them. This is the power of the concept of taytsh labelling: with it, we can reclaim, that is “retaytsh” everything, making it useful for our own contingent projects.