Abstract

In this case study, the literary device of framing is used to shed light on the systematic structure of al-Ḥarīrī’s ‘Maqāmāt’ (hereafter, Ḥarīriyya). The work has been criticised by modern scholars for being fragmented, short-breathed, and episodic. In contrast, I argue that all fifty episodes of the ‘Ḥarīriyya’ are part of a symmetric, well-devised structure, which places language at the centre of three cyclic frames: 1. the author’s introduction and afterword, in which al-Ḥarīrī dwells on the advantages of ambiguity and concealing one’s intentions, 2. the first and last encounter of the two characters, which summarise the trajectory from ignorance to knowledge (or recognition), 3. the liminal theme of “safar” or travelling, which emphasises the game of hide-and-seek led by the trickster and the narrator in different cities. The three frames share the central paradox of the ‘Maqāmāt’: concealment versus clarity; or more concretely, language as a tool for both expressing and obscuring one’s attention.

Introduction

The maqāmāt are a literary composition that combine prose and verse. This literary genre was invented in the fourth/tenth century by Badīʿ al-Zamān al-Hamadhānī (d. 398/1008), a literato who boasted of his ability to employ no fewer than four hundred artifices in writing and composition . He, thus, fashioned a series of episodes in which two contradictory characters recurrently meet to exchange anecdotes and verbosities. The first character is the narrator of the episodes, ʿĪsā Ibn Hishām, a respectable linguist who travels from one country to another to collect curious anecdotes and recherché terms, while the second is the trickster, Abū al-Fatḥ al-Iskandarī, a chameleon protagonist, who constantly changes his masks and transgresses social conventions to dupe his audience with beguiling erudition. Despite their socioeconomical, cultural, and moral differences, the two personalities are bound by their consuming interest in language and adab (meaning etiquette, ethics, and literature.).

Language is ‘the backbone of the maqāmāt as a genre: no maqāma is totally devoid of philological interest’ . Despite their obvious interest in vocabulary, al-Hamadhānī’s maqāmāt are considered today ‘refreshingly simple and straightforward’ , especially in comparison to the maqāmāt of his successor, Abū al-Qāsim al-Ḥarīrī (d. 516/1122). The main reason is that while al-Hamadhānī experimented with several plots, some of which are more picaresque and humorous than philological, al-Ḥarīrī centred his maqāmāt exclusively around the linguistic and rhetorical skills of his trickster. Emulating al-Hamadhānī’s skeleton outline, al-Ḥarīrī created Abū Zayd al-Sarūjī, the picaresque protagonist, who engaged in trickery after fleeing his occupied homeland Sarūj, and al-Ḥārith Ibn Hammām, an avid scholar who chases the hero and adab throughout the episodes. Al-Ḥarīrī elaborated his predecessor’s plot and devised a highly structured sequence of fifty episodes, which share (almost always)1In a few episodes, such as al-Sinjāriyya (18), al-ʿUmāniyya (39), al-Tabrīziyya (40), and al-Sāsāniyya (49), the trickster is identified in the beginning of the maqāma. Thus, the scene of recognition is absent. the same order:

(1) Arrival of the narrator in a city. (2) Encountering the trickster (disguised). (3) Discourse (hero’s literary performance). (4) Reward. (5) Recognition of the trickster’s true identity. (6) Reproaches of the narrator. (7) Justification. (8) Parting of the two characters.

Al-Ḥarīriyya’s episodes establish a continuous loop: arrival at a new place, exchanging adab for money, unmasking the protagonist, parting, travelling again, arriving at a new place again, exchanging adab again, and so on. Remarkably, out of these eight steps, only (3) and (7) are thoroughly developed to the point of occupying several pages, while the remaining phases are usually summarised into a few sentences. In other words, the whole chain of events is mainly devised to encircle the moment of speech, to emphasise language’s ability to conceal intent (3), as well as to clarify one’s intentions and reasons (7). Consequently, the Maqāmāt is the product of two components: a fixed repetitive plot that draws attention to the centre, and playful language that takes different shapes and styles. The structure of al-Ḥarīrī’s episodes is comparable to a certain narratological technique called ‘vision stéréoscopique’, which occurs when several narrators describe the same event from different perspectives:

the plurality of perceptions gives us a more complex vision of the phenomenon described. On the other hand, the descriptions of the same event allow us to focus our attention on the character who perceives it because we already know the story.

The repetition of the same plot throughout the maqāmāt does not enhance our focus on the characters but rather on language; or more specifically, on the various playful ways that it can be handled. In simpler words, the reason behind all the systematic repetitions in the Ḥarīriyya is to channel the reader’s attention to the only element that actually changes in every episode: words, or more generally, adab.

Unlike the Thousand and One Nights or Kalīla wa-Dimna, where the narrative thread develops via ‘nested stories’ (meaning a story within a story, creating multi-layered narrative frames embedded in each other), the Ḥarīriyya’s thread consists of a chain of encounters and departures, as well as moments of veiling and recognition. Each episode opens with a veiled character giving a misleading speech. Once the narrator reveals the latter’s identity and understands his real intentions, the encounter ends and the story stops. Thus, another episode begins, which follows, more or less, the same trajectory. These un/veiling encounters are embedded within the first and last maqāmāt, in which the two main characters meet and separate for the first and last time. In their turn, maqāmāt one and fifty are embedded within the author’s introduction and farewell, which discuss the advantages of incomprehensibility versus the disadvantages of clarity. Everything in the Maqāmāt literally revolves around one central paradox of language: its ability both to clarify and conceal. This case study addresses the three main cyclic frames, which surround the vibrant linguistic centre of Maqāmāt al-Ḥarīrī: first, the author’s discussion of writing and language in the introduction and afterword; second, the first encounter between the main characters and their last farewell; and third, the theme of travelling, which opens and concludes every maqāma.

The author’s thresholds: forfeiting one’s own shields

Al-Ḥarīrī paves the way to his Maqāmāt with a long introduction, in which he reflects on the temptations of language, the duress of writing, and the legitimacy of using jest to articulate ʿibar (moral lessons) . The most significant part of the exordium, however, is the opening lines:

إنّ نحمدك على ما علّمتَ من البيان وألهمتَ من التبيان، كما نحمدك على ما أسْبغتَ من العطاء وأسبلتَ من الغطاء

[We praise you Lord, for the eloquence You taught us and the clarification You inspired us. We also thank you for the gifts you offered, and the cover You provided.] (, my translation)

These lines set the tone of the entire book: they prepare the reader for a book that is preoccupied with speech and rhetoric (art of declamation and power of discernment), they announce the juxtaposition of opposites (clarity and concealment), and most importantly, they declare that, just as the protagonist is hiding behind different masks while deceiving his audience, so too is the author taking cover beneath a ghiṭāʾ (cover, shield).

The Maqāmat’s afterword repeats the theme of protection. This time, however, the author confesses regretfully that he lost God’s satr (concealment), because he committed the act of writing his maqāmāt:

هذا آخر المقامات التي أنشأتها بالاغترار (…) ولو غشيني نور التوفيق ونظرت لنفسي نظر الشفيق لسترت عواري الذي لم يزل مستورًا. ولكن كان ذلك في الكتاب مسطورًا

[Here ends the maqāmāt that I in my vainglory wrote (…) Had I had the grace to bewail my gilts, and to study to the salvation of my soul, I would have hidden my faults and kept my honour but it was previously ordained (…)] (, my translation)

Once the writing is over, the author loses his shield and exposes his ʿawra (double-meaning: genitals and incompleteness) before the eyes of his readers. Al-Sharīshī, a famous commentator of the Ḥarīriyya from the sixth/twelfth century, sustains this conclusion by arguing that the act of writing equals ‘displaying one’s mind on a plate before everyone’s eyes’ (man ṣannaf, faqad jaʿal ʿaqlah ʿalā ṭabaq yaʿriḍuh ʿalā al-nās) . Being exposed is a recurrent theme in the Maqāmāt. The trickster is usually exposed or recognised after he delivers his speech, as a clear sign that enunciation equals risking one’s satr, or cover. The scene of , which unveils the trickster’s true identity at the end of every maqāma, mirrors another recognition: that of al-Ḥarīrī himself. The author’s opening and closing words declare the logic of the entire collection: enunciation as forfeiting one’s right to concealment. Despite the risk, both author and trickster must continue in their literary vocations. Abū Zayd al-Sarūjī must perform to make a living, and al-Ḥarīrī cannot disobey the authority of the anonymous patron who orders the writing of the Maqāmāt.

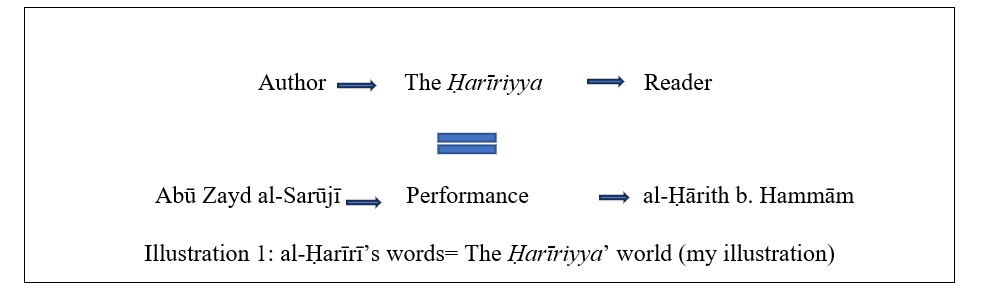

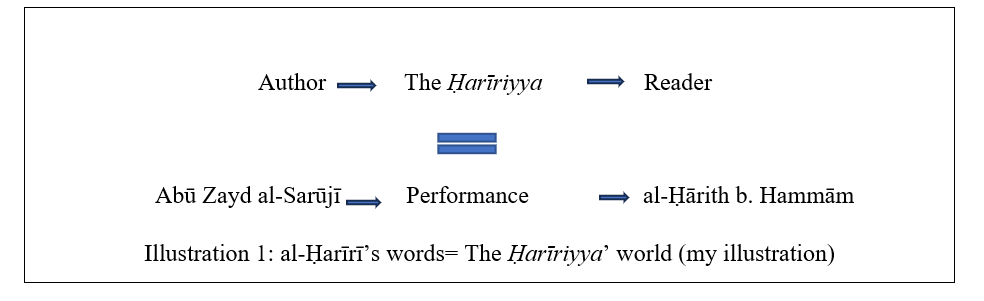

Since unveiling their minds is inescapable, the author and his fictitious trickster take refuge in the possibilities of language and make their speeches as ambiguous and as undecipherable as possible by using rare words, metaphors, writing under constraint, double-entendres, figurative language, and riddles. Language in the Ḥarīriyya functions as a tool of expression (hence, exposure), but also, at the same time, as a tool to protect one’s mind by means of wordplay and incomprehensibility. To shield the author’s mind from the reader’s judgement, the episodes are extended to the point of encompassing all kinds of gharīb (strangeness) and ʿajīb (wonder). Similar to his protagonist, al-Ḥarīrī acts as a trickster by promising entertainment and frivolity yet causing impediment and helplessness. As for the reader, he is analogous to the narrator al-Ḥārith ibn Hammām, who first endures trickery and ambiguity, before gaining his purpose (adab) and clarity (anagnorisis). The author’s introduction and afterword function as a ‘personification of narrative’ . They summarise the Ḥarīriyya’s enjeu, meaning how to speak ambiguously enough to escape punishment/judgement, and establish the similarity between al-Ḥarīrī’s words and al-Ḥarīriyya’s world.

Al-Ḥarīrī’s statements announce a dual hide-and-seek game. The first figures outside of the fiction and binds the author and his readers, while the second continues throughout the episodes between the trickster and the narrator. Both al-Ḥarīrī and al-Sarūjī express their minds ambiguously and resist intelligibility with all sorts of games, while the narrator and readers follow them from one episode to the next, seeking understanding and meaning. The author’s introduction and afterword are thus a meta-frame, reflecting on the act of writing and introducing the necessity of ambiguity for both himself and the trickster. As for the interlocuters (textual and real), they must remain all the time alert to unveil fake appearances, decipher codes, and recognise the hidden truth.

Agnoia-gnôsis

Unlike al-Hamadhānī, whose episodes lacked order, al-Ḥarīrī framed his episodes by a clear opening, in which the narrator and protagonist meet each other for the first time, and a closing episode, in which they part forever. The first and last encounters act as another frame in the Maqāmāt, embedding all the confrontations and farewells, which repeat in almost all episodes. Both embedding and embedded encounters share the same trajectory: moving from ignorance to clarity. They also share their liminal cyclic position in the text, placed in the very beginning and at the very end, whether of the episodes or the entire collection. While the framing encounters (Maqāmāt 1 and 50) act as original scenes that provide new information about the two characters, the remaining scenes of recognition act as a cliché, causing a ‘sense of being cheated, of being brought to a moment of fullness only to find that it is empty. It is also the sense of repetition, a compulsive returning to the “same place”’ .

Ignorance (agnoia)

As with most of the Ḥarīriyya’s episodes, al-Ṣanʿāniyya (M1) opens with the narrator al-Ḥārith ibn Hammām arriving to a new city and seeing a crowd that surrounds an orator giving a beguiling pious speech, which drives the audience to tears of regret and charitable donations. Intrigued by the rhetoric, the narrator follows the speaker, who takes narrow, complicated roads before arriving at a cave, where he and his disciple drink wine. The contrast between the orator’s words and deeds shocks the narrator; thus, he turns to the disciple, begging for clarification:

عزمتُ عليك بمن تستدفع به الأذى لتخبرني من ذا. فقال هذا أبو زيد السروجي سراج البلغاء وتاج الأدباء

[‘I conjure thee by Him through whom evil is averted, to inform me who this man is?’ And he replied, ‘This is Abū Zayd al-Sarūjī, The light of strangers, and crown of the literary’.]

This stance of identification cannot be entitled ‘recognition’ or ‘anagnorisis’, because the latter ‘implies a recovery of something once known rather than simply a shift from ignorance to knowledge’ . In technical terms, the scene above depicts a fresh encounter that lacks any sort of expectation or memory in order to highlight the narrator’s ignorance, to set a reference point for the forthcoming recognition scenes, and to prepare the reader for a climax of knowledge, which will only be achieved in the last scene when al-Sarūjī repents of all his misgivings and unveils all his masks—or so it may seem.

Knowledge (gnôsis)

The Ḥarīriyya’s last maqāma, al-Baṣriyya, includes two separate plots: the first happens in Basra, in the author’s hometown (see below), where Abū Zayd al-Sarūjī delivers a sermon that was supposed to trick the audience into giving him their customary alms; yet, by the end of his speech the trickster feels a genuine regret for his previous misgivings and announces his repentance:

ولست أبغي أعطيتكم بل أستدعي أدعيتكم. ولا أسألكم أموالكم بل أستنزل سؤالكم. فادعوا الله تعالى بتوفيقي للمتاب

[And I ask not your bounty, but solicit your prayers, and crave not your wealth, but desire your intercessions; and I pray God to guide me aright to repentance.]

As usual, the narrator follows the hero expecting his tears and repentance to be a mere scheme, but against all expectations, al-Sarūjī confesses:

أقسم بعلّام الخفيّات. وغفّار الخطيّات. إنّ شأني لَعُجاب. وإنّ دعاء قومك لمُجاب (…) لقد قمت فيهم مقام المريب الخادع. ثم انقلبت منهم بقلب المنيب الخاشع. فطوبى لمن صغتْ قلوبهم إليه. وويل لمن يدعون عليه. ثم ودّعني وانطلق

[By Him who knows secrets and pardons sins, I swear that my case is truly a marvellous one, and the prayer of thy countrymen is certainly answered (…) I began by acting the part of a hypocrite and ended by changing into a contrite penitent; happy then is he to whom their hearts incline favourably! And woe to him who is the object of their malediction!’ Then he bade me farewell and departed.]

The episode concludes with al-Sarūjī’s scheme backfiring on him. He, thus, repents and withdraws to his home to pray for God’s forgiveness. Driven by his usual curiosity, the narrator al-Ḥārith ibn Hammām embarks on a long journey to find the protagonist and ‘examine the truth of his statement’. He finally finds him in his hometown Sarūj, alone praying in the mosque. In this last scene, the usual crowd is absent, and al-Sarūjī’s usual eloquence is directed only to God. For once in the Ḥarīriyya, we reach a moment of pure truth: no masks, no deception, no wordplay, and ultimately, no words at all. Describing his companion’s new life, the narrator says:

ولما فرغ من سُبحته. حياني بمسبّحته. من غير أن نغم بحديث. ولا استخبر عن قديم ولا حديث. ثم أقبل على أوراده )

[When he had finished his prayers and praises, he saluted me by holding up his forefinger to me, without uttering the least whisper of conversation, or asking a single question about the past or the present; and then proceeded to resume his devotional occupations (…)]

The Ḥarīriyya depicts a unique master-and-disciple relationship. Teaching and learning adab occurs through deceit, ambiguity, and manipulation. It begins with the two interlocutors meeting and identifying each other (moment of ignorance), and ends when all the topics (adab, grammar, philology, jurisprudence, anecdotes) and styles of speaking (riddles, lipograms, rhetorical figures etc.) are exhausted. When clarity is achieved, and the master has no more tricks to play, he removes all his masks, repents his deception, settles down, and stops speaking. In this sense, Abū Zayd al-Sarūjī’s repentance is threefold: he renounces deception, discourse, and travelling.

Travelling and unveiling

Although Maqāmāt al-Ḥarīrī refers to numerous cities and countries, it hardly offers distinguishable details about any of them. It is as if nothing seems to impress the narrator or even draw his attention for being unusual or exotic. The same applies to al-Sarūjī. He never changes his tools to conform to the new culture; whether he is in west, east, or in Persia, his eloquence and playfulness remain the same. It is as if, despite their constant wandering, the protagonist and the narrator are always on familiar ground. Does this mean that travelling ‘is only a hollow frame for the episode?’ and that ‘in general one feels that it is quite unimportant where the episode takes place?’ . The answer to these questions resides in 1. the meaning of three framing cities: Sanaa (M1), Sarūj, and Basra (M50), 2. the narrator’s reflections on the act of travelling, 3. The relationship between the travelling and reading experiences.

Cities of beginning and return

The first episode of the Maqāmāt is entitled al-Ṣanʿāniyya, in refence to Sanaa, which was supposedly the first city built by Shem (Sām) after the flood of Noah . The title of the first maqāma, accordingly, emphasises a fresh start by referring to a ‘mythical’ beginning of civilisation, settlement, and urbanism. Paradoxically, the sense of settlement breaks by the end of the episode, when Abū Zayd al-Sarūjī is identified as ‘the light of strangers’ (see above). The trickster chooses ‘the oldest city on earth’ to announce himself as the leader of strangers who would never adhere to the conventions of urban life and stability. This is most evident in his chosen place of hiding: a cave that brings to memory the primitive ways of living. Sanaa serves two purposes in this maqāma: it establishes a sense of beginning and emphasises the protagonist’s transgression of social and historical conventions.

After Sanaa, the common reference for a new beginning (at least for the Semitic groups), al-Ḥarīrī chooses for the closing episode two cities that have personal value: Basra, his hometown, and Sarūj, his protagonist’s birthplace. To understand the significance of this choice, it is important to quote Monroe’s description of space in al-Hamadhānī’s Maqāmāt:

Instead of being portrayed in their homes, among family and relatives, the characters are usually encountered abroad, in inns, mosques, taverns, caravans, and always in strange towns (there is in Hamadhānī no maqāma of Qumm nor of Alexandria)—in other words, in public places, or in transit: environments and situations where the individual is reduced to social anonymity and alienation.

If Hamadhānī denies his characters’ homesickness and social bounds, depicting them as rootless drifters, al-Ḥarīrī makes his trickster more ambiguous, advocating for rootlessness at times, and yearning for home at others. He also allows his trickster to reflect on home as a space of defeat and trauma (for example, see the envois in al-maqāma al-Najrāniyya (42), and al-Maqāmaal-Ḥarāmiyya (48)), and as a lost heaven (see the envoi in al-Maqāma al-Malṭiyya (36)). On several occasions, he positions the main characters in familiar surroundings: in their households, surrounded by family and friends.2The narrator is always surrounded by elites that resemble him and welcome him. As for Abū Zayd, he is occasionally accompanied by a wife or a son. Additionally, in al-Maqāma al-Ṣūriyya (30), al-Sarūjī is officiating a wedding in the presence of his tribe Banū Sāsān, while the narrator plays the role of a party-crasher.Finally, al-Ḥarīrī allows his protagonist to spend his last days in his own town (M50) and to die on his bed (M49). The Ḥarīriyya’s characters are not in perpetual ‘social anonymity and alienation’, but rather nostalgic strangers, who occasionally catch a breeze of familiarity in their journeys, and who eventually return home.

Appropriating the end

The Maqāmāt of al-Ḥarīrī end in Sarūj, which is the city to which al-Sarūjī returns after the Byzantines have left and after he has declared his repentance, perhaps to insinuate that trickery, ambiguity, and crime only happen elsewhere, away from home. Homecoming, thus, equates to a return to balance, both for the city that regains its independence and for the hero who finds his way back to God. Remarkably, despite the significant value of the protagonist’s city in the narrative, the author does not name the last maqāma al-Sarūjiyya, but rather al-Baṣriyya, referencing his own hometown. Instead of focussing on the long-awaited return home which al-Sarūjī expresses nostalgically in several poems, the author turns the last maqāma into a long-detailed panegyric of Basra and, most importantly, of the inhabitants of Basra, who achieve what no other audience could in the Maqāmāt: to change the trickster and make him repent. Al-Ḥarīrī sets the ultimate scene of recognition in his city to indicate that only Basra—and no other from all the other cities mentioned in the Maqāmāt—is capable of unmasking the shrewd chameleon trickster; or, in Cave’s words, only Basra is able to ‘domesticate the alien’ .

Al-Maqāma al-Baṣriyya suggests two readings: first, that al-Ḥarīrī wrote his episodes as a travelogue that mixes fiction with reality: the trickster and narrator assume the strangerhood and the duress of travelling, while he remains within the familiarity of his hometown, which might also answer the question why there are no descriptions or meaningful details about any city other than Basra in the Ḥarīriyya.3Reading al-Ḥarīrī’s biographies proves this to be the case; although he lived in a vibrant era in which the acquisition of knowledge depended on travelling, al-Ḥarīrī spent his whole life between two cities: Basra and Baghdad. See: al-Ṣafadī, al-Wāfī, 17/219, al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Tārīkh Baghdād, 21/106, Qiftī, ʾAnbāh al-ruwwāt, 2/126, Ibn Khallikān, Wafayāt, 4/65, etc.Second, al-Ḥarīrī splits the end into two parts: to Sarūj, he assigns settlement and silence, and to Baṣra, confession, discovery and speech. Regardless of the two readings, blending the two homelands in the last maqāma brings the author and protagonist closer (illustration 1) and concludes the protagonist’s long journey with a triple return: to God, to the independent homeland, and to the author’s familiarity.

Safar

Unlike the trickster, who had to flee his homeland and rely on deception, chameleonism, and playful language to survive, the narrator al-Ḥārith ibn Hammām chooses his journeys voluntarily and rationally. In the opening of each maqāma, he describes his voyage, company, motives, and purposes. He also reflects occasionally on the meaning and function of travelling or safar. For instance, he begins al-Maqāma al-Ramliyya (M31) as following:

كنتُ في عُنفوان الشباب ورَيْعان العيش اللّباب أقلي الإكتنان بالغاب. وأهوى الاندلاق من القِراب لعلمي أن السفر ينفِج السُّفَر، وينتج الظفر، ومُعاقرة الوطن تعقِر الفطن .

[In the dawn of youth, and the prime of early life, I used to be most averse from the seclusion of home, and to prefer being at large to remaining in retirement, well knowing that foreign travel replenishes the stores, and generates a constant increase of prosperity, but (…) keeping close at [sic] home injures the faculties, and inevitably brings him who stays there into contempt.] )

The narrator compares safar (travelling) to waṭan (homeland). The first is connected to movement, which generates vigilance, wealth, and knowledge, while the second equals settling down and sterilising one’s mind (taʿqir al-fiṭan). Similarly, in al-Maqāma (45, also entitled al-Ramliyya), he quotes the ‘men of experience’ and describes travelling as ‘the mirror of wonders’ (akhadht ʿan ūwlī al-tajārīb anna al-safara mirʾāt al-ʿajāʾib, 514). In contrast, in al-Maqāma al-Marwiyya (38), this time citing a ḥadīth,4In his commentary, al-Sharīshī clarifies that this line is actually an allusion to the Prophet’s Ḥadīth: السفر قطعة من العذاب، يمنع أحدكم نومه وطعامه وشرابه، فإذا قضى أحدكم نهمته من وجهته فليعجل الرجوع إلى أهله. Ibn Hammām declares travelling to be part of pain and suffering (qiṭʿatun min al-ʿadhāb, 417).5These two contradictory attitudes might seem unusual to the contemporary reader, yet during premodernity where ‘training in ambiguity’ prevailed , the contradiction was completely normal.Despite its pains, the narrator admires safar, because to him, it equals uncovering the unknown, both geographically and intellectually. Geographical discovery manifests itself in the continuous journeys and movement through space, while the intellectual discovery reveals itself through encounters with the trickster and the unmasking of his multiple identities. Al-Ḥārith, for example, describes recognising the trickster in Al-maqāma al-Baghdādiyya (13), saying:

فلمّا انسرَبَت أبّهَة الخَفَر، رأيتُ محيّا أبي زيد قد سَفَرْ

[When the splendor of darkness faded, the face of Abū Zayd was revealed.] (, my translation)

Similarly, al-Ḥārith describes the moment of anagnorisis in al-Maqāma al-Raqṭāʾ (26) as follows:

حين سفرَ عن آدابه وكَشّر عن أنيابه، عرفتُ أنّه أبو زيد

[When he revealed his adāb and showed his teeth, I recognised that he was Abū Zayd.] (, my translation)

The association between travelling and unveiling is not invented by al-Ḥarīrī, nor by al-Hamadhānī. It is already present in the Arabic root sfr. Lisān al-ʿArab, for instance, gives the following interpretation:

وسُمّيَ المسافر مسافرًا لِكَشفِه قناع الكِنّ عن وجهه، ومنازل الحضر عن مكانه، ومنزِل الخفض عن نفسه، وبُروزِه إلى الأرض الفضاء؛ وسُمي السفر سفرًا لأنّه يُسفِر عن وجوه المسافرين وأخلاقهم، فيظهر ما كان خافيًا منها

[The traveller (al-musāfir) is named as such, because he removes the mask of home (kinn) from his face, urbanism from his space, and comfort from his spirit. Hence, he steps out to the open land. As for travelling (al-safar), it was named as such because it unveils (yusfir) the faces of travellers and their character and uncovers what was hidden.] (, my translation)

Based on the entanglement of travelling and unveiling in this interpretation, it is no wonder that al-Ḥarīrī assigned the cadre of travelling exclusively to his narrator, who is also the agent of recognition. Through the act of travelling and narrating the journey (in the opening and end of every maqāma), al-Ḥārith ibn Hammām unmasks the notions of ‘home’, ‘space’, and ‘spirit’ before he achieves the point of unmasking his travelling companion: Abū Zayd al-Sarūjī, ‘the light of strangers’. The significance of travelling changes in the Ḥarīriyya depending on the character in question: in Abū Zayd al-Sarūjī’s case, travelling accentuates his strangerhood and his longing for home, but in the narrator’s case, it is only a medium to highlight his abilities in decoding and unveiling signs—in other words, his skills as a reader.

Travelling, reading, and spiritual quests

In his book Recognitions, Cave argues that:

there is plenty of evidence to indicate that anagnorisis has always contained the germ of an equivocation between reading and recognizing […] recognition seems to provoke ‘reflection’ (in the sense of a more or less aggressive mirroring) […] it happens to be present also in Greek etymology: anagnôstês means ‘reader’.

Al-Ḥārith ibn Hammām is a narrator, a traveller, an identifier of the trickster, and also a reader. Blending all these functions, Ibn Hammām becomes a key figure for the real reader who exists outside of the work and undergoes the same journey from ignorance to knowledge as the narrator. Correspondingly, Kilito argues:

Maqāma dramatizes the act of reading indirectly. The travelling that opens every maqāma is analogous to the reader’s move outside his familiar entourage towards a world made of paper […] the parting of the two characters stops the flow, blocks the rush with a brier that takes the reader back to the starting point. Nevertheless, the experience is repeatable, and the trip is renewable. (, my translation)

Ibn Hammām and al-Sarūjī in their repetitive, spiral travels are always joined by a third character: the reader. The latter’s journey starts with an announcement of travelling, reaches its climax during the protagonist’s speech, and ends when the two characters part. Unlike the characters who immediately start a new journey in the following maqāma, the reader’s pace is not monitored by the author. They can always choose to ‘repeat’, ‘renew’, or stop the journey at any point along the road/the Ḥarīriyya.

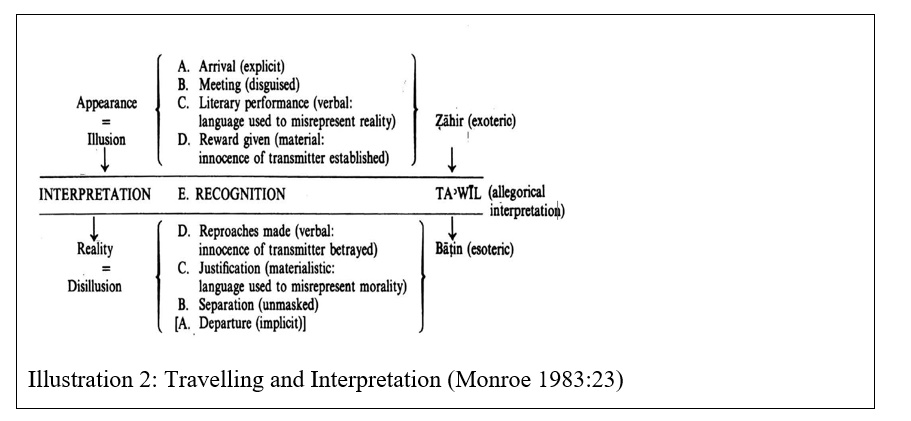

Correspondingly, Monroe creates the structure of the maqāmāt by focussing on the two acts of travelling and interpretation. He, thus, draws the following scheme:

According to Monroe, moving from arrival to departure is equivalent to moving from appearance to reality and from illusion to disillusion. The liminal stage between the two is the moment of recognition, in which the act of interpretation occurs. As elegant as Monroe’s symmetrical illustration may be, it has one critical flaw: the recognition scene only happens in the last third of the episode, which means that the ‘reality’ part (D, C, B, A) is too brief to reflect symmetrically the first half where most of the action happens (A, B, C, D). The reason for centralising the moment of anagnorisis is obviously moral. To Monroe, truth is better than pretence, and disillusion is favoured over illusion. The Maqāmāt of al-Ḥarīrī, however, are too playful and ambivalent to admit to modern moral conventions (see ). Monroe’s structure, nonetheless, captures the vibrant tension that prevails throughout the maqāmāt between appearance and essence, performance and intent, or simply, as al-Ḥarīrī already announced in the muqaddima, between bayān (clarity) and ghiṭāʾ (concealment).

The Ḥarīriyya, in short, combines two forms of travelling: the first is thematic, entangled with notions of strangerhood, space, memory, and nostalgia. It ends once the hero finds his way back to God and home. The second is hermeneutic, addressing acts of reading, decoding signs, and pursuing language. It thus ends once ambiguity ceases, and once surface matches reality. Despite the deference between the two journeys, their ends are synchronised and even identical: returning home equals silence for the trickster, and repentance signifies the end of the journey for the narrator. al-Ḥarīrī’s Maqāmāt continue as long as ambiguity, masks, and trickery are in action. Once clarity, repentance, and settlement occur, the story is by default over. In other words, al-Ḥarīriyya’s third frame is given by a dynamic relationality between concealing and revealing mirrored in the figures of the narrator and the trickster.

Conclusion: reframing the Ḥarīriyya within its own terms

For centuries, al-Ḥarīrī’s semantic and aesthetic playfulness worked wonders on readers to the point of characterising his maqāmāt as iʿjāz (inimitability).6For example, see Yāqūt’s praise of the Ḥarīriyya in: . This degree of praise and appreciation is predictable in the premodern period of Islam, in which scholars had a ‘training in ambiguity’ , which made them favour the complicated and ambivalent over the explicit and unequivocal. Once modernity and its new measures of clarity, control, and structure prevailed, maqāmāt readership changed tack, and Ḥarīrī’s style was criticised for being pompous, repetitive, and episodic. A case in point is that al-Bustānī laments classic Arabic literature for being ‘short-breathed’, ‘clumsy’, ‘lacking harmony’, and ‘cold’. Instead of inheriting great tales and epics like Europeans, Arabs were only left today with ‘maqāmāt, nawādir, and aḥādīth’, meaning short, fragmented narratives that were unable to produce an elaborated literary genre such as the novel . There are two critical problems with such a statement: first, the self-orientalist attitude that underestimates everything that originates away from the European centre; second, the anachronistic perspective which criticises the past for not predicting that in the far future a genre called the novel would be created and esteemed, and Arab readers would need a practice in long narratives beforehand. This and other similar statements do not allow adab to be read in its own terms, but rather project a Eurocentric perspective, rooted in the moment of speaking and its power dynamics. If al-Bustānī and others had considered Maqāmāt in its own terms and studied its structure through the lenses of a literary device such as frames, they would have noticed that, although the work includes fifty episodes, it is not episodic, fragmented, or ‘lacking harmony and uniting themes’ . It is, rather, a symmetrically-structured work, framed by liminal themes and cyclic scenes that draw the reader’s attention to the one central point: playfulness of language and its paradoxical ability to veil thoughts and unveil truth, depending on the speaker’s intent and the reader’s hermeneutic tools.