Abstract

René Descartes employs the term “fable” or “fabula” in numerous instances throughout his work, yet he never provides an explicit account of his understanding of the term. In my paper, I aim to establish an understanding of this usage in relation to the overarching theme of framing narratives. I highlight that, despite Descartes’s texts generally being decisively non-narrative and characterised by systematic and methodological approaches, their very nature depends on autobiographical, exemplary, and even “fabulistic” moments. These moments are inscribed in the text yet only brought forth as means to an end that Descartes envisions for his philosophical prose. Applying our terminology to this corpus allows us to observe that when it is a narrative that does the framing, the framed need not necessarily be narrative as well. On the contrary, the outer or earlier stage of Descartes’s progression towards a binding and irrefutable philosophical method of thought is presented as a necessary, albeit negligible, detour towards the deeper insights of his work. Descartes regards his “fables” as narrative tools that are only temporary components of his textual compositions. Once they have fulfilled their purpose, there will be no further need for moral advice, good examples, or biographical identification. When—according to Jean-Luc Nancy—‘Mundus est Fabula’ is an apt summary of Descartes’s so-called “methodological doubt”, this maxim applies only until further notice; with regard to their temporal structure, the global fables of Descartes’s world are written to be outlived by their “morals”—the overarching “way towards knowledge” of his future “method”.

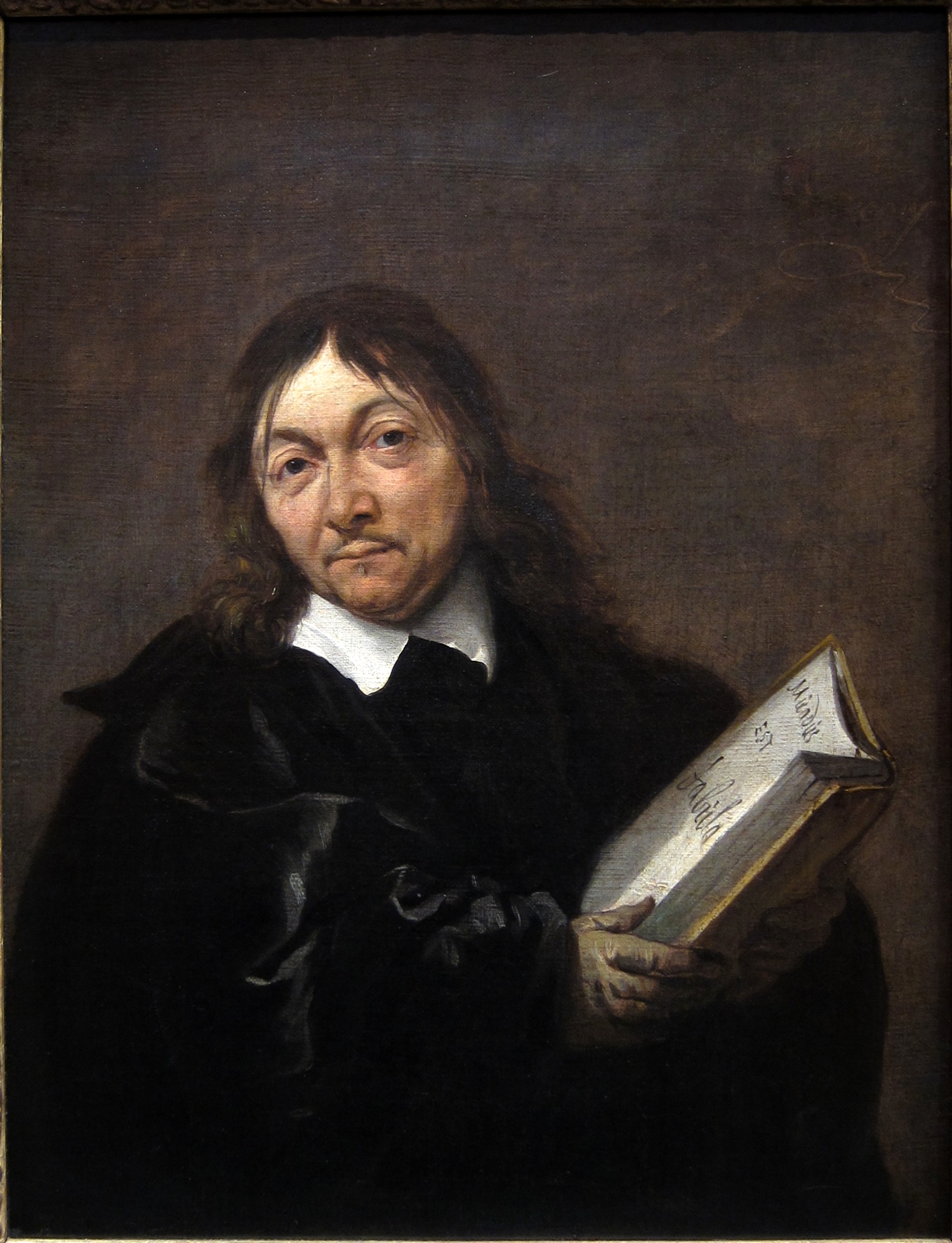

In the work of René Descartes, the term “fable” plays a crucial role in his inauguration of a new and “early modern” methodology of thought. Despite his fame as a central figure in the constitution of a specific form of epistemological rationalism that has shaped modern philosophy significantly, his writing is also to be read as an ongoing experiment with different genres; his most important texts, the Discours, the Meditationes, and the posthumously published Regulae, show a variety of textual attempts at his lifelong project, the establishment of a new method for scientific thought.1 On Descartes’s genre trouble: ‘His attempts to fuse the rhetoric of persuasion with the precision of rational argument are evident in his experiments with philosophic genres. Despite his austere recommendations about the methods of discovery and demonstration, he hardly ever followed those methods, hardly ever wrote in the same genre twice. The assortment includes: Rules for the Direction of the Mind, Meditations on First Philosophy, The Principles of Philosophy, Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting the Reason, a dialogue, a treatise, essays, and the letters of a vast correspondence. Using these established genres gives Descartes the benefit of theft over honest toil’ . All those texts consist of different approaches to the uniting ‘method’, which Descartes understands as necessary groundwork for future progress in all the sciences; they thus qualify as different steps on a general way his Ego wants to go. Within these ‘paratextual’ marks, the fable does not play by the rules; although he repeatedly and prominently characterises his attempts at a method as ‘fabulistic’, none of his texts is explicitly introduced as fable. Jean-Luc Nancy has shown that the genre name has nonetheless become allegorical for Descartes’s thought in retrospect. Insofar as the ‘method’ comes as the promise of the via regia of the sciences, the fable wanders off its path —in using the term, Descartes, at first, describes the status of his texts as merely preparatory and provisional, as a little story that stands in sharp contrast to the methodological and even revolutionary claim of his (1637). However, over time, the fable becomes more important to an extent that, as the slogan Mundus est fabula indicates, the fable undergoes a generalisation of even global significance. In his iconic portrait from around 1647, painted by J. B. Weenix, we see the philosopher standing in front of a dark, void background, facing the viewer with a more or less inviting face; all that is left in this pictorial world is an open book he is holding in his hands. The book has very generous typesetting, allowing the viewers of the portrait to become readers, too; the whole page is filled with one Latin phrase, consisting of the three words: Mundus est fabula. According to Jean-Luc Nancy, this can mean either ‘The world is a play or, more literally, ‘The world is a fable’ ; either way, the little genre formerly introduced as a mere byproduct has become a term of global significance, describing a world that is but a fable, a play, or a dream. Descartes, the thinker of maximal reduction, of even metaphysical concentration, and of the fundamentum inconcussum of the modern Ego, is shown as if he were holding his own speech bubble, summarising the essence of his work: on the one hand, there is nothing truly certain and evident besides the existence of the ego and the indubitability of its doubt itself; on the other, the whole world appears to be nothing but a fabrication, a story, or a dream that an evil demon has written or programmed to deceive us.

Whether Descartes himself or the painter has decided what the composition of the portrait should consist of, it is certain that for the seventeenth century, the work of Descartes and the Latin sentence of the fabularity of the world were intrinsically connected.2‘In at least three crucial moments throughout Descartes’ career, he has recourse to an interesting choice of technique: the fable. In the beginning of The World, or a Treatise on Light, the Discourse, and in a late portrait made of him, Descartes (or a book he holds in the portrait) refers to his work (or to the world itself) as a fable’ . Mundus est fabula can be read as a signature of the thinker summarising his impact on European thought—the world as we have known it has been a fictional one that now will be progressively explored according to the epistemological guidelines of the Discours and the Meditationes. His ‘methodological skepticism’ developed in both texts has left nothing untouched—the world, its creator, and even the mathematical truths could be different than they seem, and everything might be just an illusion of a mind that lacks evident truths. The insatiable doubt of Descartes has tainted everything, and it would be naive to assume that the world, the truth, or even god might be just given facts; they are fables, fabulations, mere schemes of the mind that bear no essential truth by themselves.3‘The cogitating ego is the solid atom of reality engulfed in a universe of likely reality. In this way, the reality of the cogito makes all other entities that inhabit the physical world fictitious and imaginable, pliant to the power of virtual existence’. Giglioni combines his reading of the Discours with one of Le Monde of 1632/33, thus before the Discours and its methodological decision; here, Mundus est fabula would have meant that the world itself is a fantasy, resulting from fabulations of the mind. When Descartes lays the groundwork of his epistemological program later, this image is reshaped, and the “fable” appears in a different and significantly less pejorative light’ .

However, this understanding would be oversimplifying, up to the point of a complete reversal of Descartes’s famous argument. After all, such a global skepticism is not only far from what he tries to achieve, but rather the adversary his project tries to overcome . His doubt is fatal, of course, but it is, insofar as it is methodical, designed to arrive at a certain point, from where finally, the difference of truth and illusion, fable and reality, can be discerned with all certainty, and there is nothing left to doubt any more. The assumption of the world as a fable is part of his path to method, and thus only deployed as means to an end; the world he casts into doubt serves only to establish a deeper, more irrefutable knowledge that, once achieved, provides us with a new way to look at the world, now less prone to deception.

Accordingly, the motto Mundus est fabula cannot simply mean “everything is a lie” but evidently must have a second meaning. The connection between “fable” and narrative in general, as a fictional story to be overcome, seems misplaced in this scenario. The world has intentionally been transformed into a fable-like realm as part of a method to end all fables. It is not surprising to see that in Descartes himself, the term is not used to denote myths and deceptions in a general and pejorative way. When he affirmatively uses the term in the introduction to his famous Discours, the fictional character of fables seems to be balanced out by their didactive, moral, or pedagogic—or even, methodological—value. Fables provide frames that can help us get on the right track:

Ainsi mon dessein n’est pas d’enseigner ici la méthode que chacun doit suivre pour bien conduire sa raison, mais seulement de faire voir en quelle sorte j’ai tâché de conduire la mienne. Ceux qui se mêlent de donner des préceptes se doivent estimer plus habiles que ceux auxquels ils les donnent; et s’ils manquent en la moindre chose, ils en sont blâmables. Mais, ne proposant cet écrit que comme une histoire, ou, si vous l’aimez mieux, que comme une fable, en laquelle, parmi quelques exemples qu’on peut imiter, on en trouvera peut-être aussi plusieurs autres qu’on aura raison de ne pas suivre, j’espère qu’il sera utile à quelques-uns sans être nuisible à personne, et que tous me sauront gré de ma franchise.

[So my aim here is not to teach the method that everyone must follow for the right conduct of his reason, but only to show in what way I have tried to conduct mine. Those who take it upon themselves to give direction to others must believe themselves more capable than those to whom they give it, and bear the responsibility for the slightest error they might make. But as I am putting this essay forward only as a historical record, or if you prefer, a fable, in which among a number of examples worthy of imitation one may also find several which one would be right not to follow, I hope that it may prove useful to some people without being harmful to any, and that my candour will be appreciated by everyone.]

How can we reconcile the text of the book in the portrait with the explicit and affirmative insertion of fabulae into Descartes’s texts? As introductory devices, the comparison of his writing to ‘a story or, if you prefer, a fable’ might be incidental to the whole of the text, yet it turns out to be crucial for the legitimacy of Descartes’s enterprise altogether. The fable, here, is useful in order to arrive at his goal. In claiming not to present his method as such and to prescribe it here, the Discours releases itself of the immense responsibility a thought-through scientific procedure fit for all purposes would require; in contrast to its title, the Discours de la méthode is not a summary of the method itself, but its story, its own way of coming into existence that is intrinsically linked to the author’s biography. But this story is further specified as, ‘if you prefer, a fable’. The use of this sideways approach towards narration in the introduction does not restrict itself to the excusatio propter infirmitatem that a seventeenth-century exordium would contain (; ). In reducing the scope of his treatise, the first part already takes back what the title might have promised; it is a talk on method, not the method itself that will be given here, and it comes in the form of a story or, moreover, a fable. Descartes will begin to narrate his life story and his reflection on it as he develops the central traits of his scientific approach, yet he does so for his person alone, with the reduced liability of a single, yet exemplary case. Reading the Discours is not an introduction of precepts and instructions, but an invitation to follow our epistemological hero in his steps towards certainty. By imitation and adaption, we will see how he arrived at the promised method that might be useful to us.

But Descartes specifies this even further; it is the fable, not the autobiography or the story in general that serves best to describe the Discours. While Descartes is trying to mitigate expectations and to prepare his readers for a preliminary approach to method, the recourse to questions of genre is not limited to narration. In his correctio, the fable (fable) is introduced in distinction to the story (histoire). If we like it better (quand on l’aime mieux), we can read what follows as a fable because the case study in methodology linked to the personal views of one René Descartes could function as “examples”. The openness to narrative in general is transposed to a connection to exemplum-literature (see ) and, in this context, to the fable in particular. It is evoked insofar as its paradigmatic function and its way of enclosing a deeper meaning—a moral or practical truth—becomes instructive for Descartes and for his anticipated readers.

What the Discours wants is nothing but this demonstration; the status as a fable does not simply mean that Descartes thinks of himself as a storyteller. This becomes obvious when, in framing his text accordingly, he marks the difference between story (histoire) and fable (fable) explicitly in accordance with his deliberation on the matter later on. History or story is the narration of past events that might depict them as they happened or, in many cases, give a deceitful image of the narrated events in order to array them in beautiful language. The fable, too, is fictious in nature, yet has a different function altogether; in lieu of telling the truth about the past, fables produce morals the reader or listener shall adopt for themselves. Exemplary cases of universal applicability come in the form of short narratives that the audience has to apply to their own situation, and the moral kernel of the story is what ultimately legitimises the whole. In other words, the truth of a fable is not lost in its make-believe character but results from it. As Jean-Luc Nancy has argued:

Descartes proposes his Discours as a fable. This is not a comparison; his text does not imitatively borrow the traits of a literary genre. But it is presented as fable, and it is precisely as fable that one must deal with it. Hence what we find here is not exactly the motif of a fiction, which, although opposed in its essence to truth, would serve as its instrument or its ornament. If fable here then is to introduce fiction, it will do so through a completely different procedure. It will not introduce fiction ‘upon’ truth or beside it, but within it.

As Nancy himself situates this relationship in his essay on Descartes, the fable, unlike the story in general, is a framing device. It is not a story that tells us something about the world, but a way of producing truth—the moral that is encapsulated within the narrative of limited length. If stories, particularly fictitious ones, can represent events and even worlds of dubious character and are by themselves unable to guarantee that this representation holds some claim to truth, then the fable’s made-up narrative, likewise, does not have a problem of legitimacy simply because the dream-like status of, for example, animals conversing and mythic creatures interacting has a merely ornamental function for an inner truth that, once understood, transcends the fabulist embellishment. Unfortunately, in asking about the impact that inserting this genre title, ‘Fable’, has on the text, we can find little binding evidence that could help clarify the invested understanding. Insofar as he did not make the fable part of his experiment with different forms, the evocation of the term does not only remain obscure, but cannot be explained away by adapting some predefined concept Descartes might have had in mind when using the term himself. Any such adaption would end up risking an anachronism—what, in itself, would not be too great of a problem—and assume that for the philosopher who enjoys the genre games, it is absolutely clear what fables consist of. However, as can be seen in the quotes given here, Descartes’s very own use of the term shows that he is far from decided on the matter; while it would be possible to assume that, for him, fables are narrative structures of a limited length with an introductory and illustrative function—much like, for example, the Aristotelian Rhetoric defines it4An early deliberation on various forms of rhetorical narration can be found in Aristotle’s Rhetoric (1393a-b), where he explicitly differentiates between ‘parables’ and ‘fables’ (logoi), as told by Aesop (See ).—we would neglect the fact that, even in the narrative recollection of his own upbringing, he decisively distances himself from the canon of Humanist education that has led him to search for a truer and more secure method for knowledge creation in the first place. If we were to take the Aristotelian understanding for granted, we would face the fact that the works of Descartes themselves have had some significant effect on the redefinition of the genre that was initiated by La Fontaine only shortly after Descartes’s writings. But contemporaneity must not be mistaken for consensus, especially when La Fontaine’s depiction of animals that carry wisdom can be read against the backdrop of the rigorous devaluation of the animal world Descartes is famous for.5‘In the years after 1668 La Fontaine took much greater interest the question of animals and their relation to man. Followers of Descartes and Gassendi were debating such ideas as the “bête machine” and “l’âme des bêtes”. Did animals have minds and souls? What were their powers of memory, of thought, of imagination? The opinions of La Fontaine can be found in some of his philosophical fables, notably in two of them which he called Discours: the Discours à Madame de La Sablière at the end of Book IX and the Discours à Monsieur le Duc de La Rochefoucauld. For this context, see . In the introduction letter to his Fables in 1668, La Fontaine presents his short stories as modelled after the classic author of the genre, Aesop, employing the very metaphors invested in Descartes’s understanding:

Tout cela se rencontre aux fables que nous devons à Esope. L’apparence en est puérile, je le confesse; mais ces puérilités servent d’enveloppe à des vérités importantes […] Esope a trouvé un art singulier de les joindre l’un avec l’autre. La lecture de son ouvrage répand insensiblement dans une âme les semences de la vertu, et lui apprend à se connaitre, sans qu’elle s’aperçoive de cette étude, et tandis qu’elle croit faire toute autre chose.

[All of this is found in the Fables that we owe to Aesop. The appearance of them is childish, I confess; but these childish aspects serve as a cover (or, verbatim: an envelope, S.G.) for important truths (…) Aesop has found a unique way to combine them. The reading of his work gradually spreads the seeds of virtue in a soul and teaches it to know itself, without it realising this study, and while it thinks it is doing something completely different’.] (My translation)

La Fontaine is captivated by both the instructive and expressive qualities of fables. To him, they are containers or “envelops” of wisdom, where the real value lies in the content rather than the form. The defence of this genre hinges on the idea that these brief stories serve as frames, holding profound wisdom beneath a surface of illustration, as pictures represent their objects.6‘A fictional narrative which portrays a truth’. Their worth is measured not by their formal qualities but by their ability to bring about moral improvement in the reader .

Much like Descartes’s autobiographical account, the seventeenth-century discourse on fable regards them as effective tools for education, understanding them in a merely instrumental way, as ‘fables en apparence, en effet veritez’, as de la Motte puts it.7A century later, Lessing will, in criticising de La Motte and others, reduce the scope of fables to the representation of moral principles in an illustrative singular case . See ; . Descartes’s dual stance of praising and devaluing the narrative form, of using it as a means only insofar it leads to the respective and effective end, is not unique. However, it is challenging to derive a rigid definition of the term from external sources related to Descartes’s Discours, especially as later adaptations are themselves framed in relation to Descartes. Even with adjustments, achieving sufficient conceptual clarity to illuminate the theoretical foundations in Descartes’s use of the term remains elusive. What we can say with some certainty, drawing on genre-theoretical intertext, is that the mere equating of fable and fiction falls short. The stories that Descartes refers to, between the memory of his own childhood days and the enigmatic sentence—“Mundus est fabula”—of his portrait, in both cases must be more than just stories. They are told here to gain access to the deeper truths and metaphysical axioms that he is interested in, and he uses them as thresholds for complex thoughts that he himself, as well as his readers, have to cross on their way to clear and distinct insights.

At the theoretical intersection of pedagogical storytelling and the metaphysical-epistemological justification of one’s own discourse, Descartes’s understanding of fabulae is to be conceived as instances of parergonality, serving as framing narratives in a distinctive manner. In contrast to conventional narratives, where short extra-diegetic moments encapsulate a story, Descartes’s experimental philosophical prose reverses these roles. Within his various attempts at a concise methodology for philosophy and science, any narrative present is deemed legitimate only as a preparatory stage of his texts—a tool both illustrative and didactic, paving the way for subsequent content. This characterisation holds true in both instances where Descartes employs the term “fabula”. When he refers to the biographical account as “fabula”, it serves to underscore that the example he presents—his own life story and the path leading to the famous Ego—is irrelevant to the illuminating insights derived from it. In these cases, it is ‘a fable in appearance, yet effectively, the truth’. Similarly, the motto Mundus est fabula holds significance when read against the backdrop of the Discours’ overarching argument. The assertion that behind everything that might be fabricated, dreamed of, hallucinated, or manipulated by evil spirits and the limitations of ourselves, there lies an unshakable truth becomes evident. Even amid the greatest doubts about the world, as we experience it, there is an enduring truth hidden. Once revealed, this truth—the necessity of the cogitant subject that cannot be doubted any more—will never be forgotten, and, moreover, we will see that it had been concealed within the fabric of the world all along. If the world, in its entirety, is a fable, then it contains its inner truth, to which all possible sources of mistakes have pointed.’ The subject referred to in the Discours’ soliloquy is discovered enveloped in a doubtful world, and the methodology ensures that this world can be rediscovered once the foundation of the meditating “I” is secured.

In both of these adaptions of the term for Descartes’s self-description, the conventional Aesopian fable is a model for the constitution of what the philosopher understands as ‘method’. His fables are framing narratives, insofar as they are framed as stories that stand in for, or supplement, something text and mind will develop only later, thus “framing” or anticipating the philosophical discourse; and at the same time, they are introduced (or: framed) as mere stories, just provisional and didactic means that are not to be taken at face value. These fables possess only a temporary significance; they are destined to be supplanted by the method once it comes into effect, rendering illustrative stories unnecessary once the clear and distinct means of knowledge have been identified.

In this sense, the detour via fables, autobiographical accounts, and exemplary cases within a methodological approach can be forgiven; since their moral, once lifted, makes up for them indubitably. Insofar as truth, indubitable and unshakable as it will turn out to be, is the goal of the Discours in toto, every step on the way, albeit a fictious one, is already informed by it, or will soon be retroactively legitimised. While Nancy seems to think that the method becomes a fable, he stresses the dependency of Descartes’s way into method on something presupposed; the logical problem, of course, being the impossibility of methodologically constituting one’s method. The only way to avoid any circularity is precisely by side-stepping the straight path to truth in the form of a biographical and singular report on Descartes’s life that has given him insight and led him to knowing the founding principles of his thinking. In other words, a specific outside-the-text is necessary for the project to start—a threshold or, as a matter of fact, a frame that provides an entry to the Discours. The narration of the self has the institution of the speculative ego as its telos from the start—thus, in re-telling how he arrived at it, we are able to reconstruct its way. So, in contrast to Nancy’s reading, the difference between method and fable remains not only intact but is of vital importance; without its ability to enclose a certain truth, to encase the ever-present insight into the intuitive truth of the mind that ego cogito, ego existo, the method would not have been identified at all. The story is negligible as narrative, since it can only depict a singular case for the general mode of inquiry; however, in its fabulist function to contain this one elementary truth, in is indispensable. Thinking of the fable as a “framing narrative” thus allows us to reconstruct the implementation of the narrative strategy within Descartes’s rationalistic world and world-view: the truth contained in it—the knowledge already gathered that is necessary for a method to arise—has the status of a fable that must be read correctly to harvest its kernel of truth, as small as this might eventually turn out to be. Everything up to his meditative moment has been a preparation for the first secure step that disregards all possible deception and logical error; the inner truth of his egocentric logic has been embellished by a life story that might not provide one with deeper knowledge in itself, but with the frame in which the rational “I” can operate. The fable the Discours is telling is the framing narrative for the most reductive intellectual operation of all, the insight into the Ego itself, from which all future insights will stem. Mundus est fabula, in this sense, means that the uncompromising reduction of the Ego alone as fundamentum inconcussum must consider the world in total as a fable, which is best understood if one disregards all its varieties and singularities, except for this one and unquestionable Ego that stands at its end as the moral of it all. Thus, the world of the historical Descartes, as he renarrates it in the Discours, is a fable that had but one epistemological relative moral to be unpacked: without its packaging, the method would have remained unknown. The frame is an arbitrary one—since it might have been any person, any young scholar of a comparable upbringing, who discovered the intuitive truth of the irreplaceability of the Ego—yet necessary, insofar as it guarantees the readers a way into the method that would not have been describable without it. The hierarchy of the two is telling, since in his investigation into a possible fundamentum inconcussum, it would have been impossible to legitimise the method itself before its discovery. For this reason, the position of the fables in his work is as central to their implementation as their didactive use; as Griffith explains in his illuminating monograph:

[…] that Descartes has recourse to the fable and to appeals to other imaginative forms at crucial moments in the course of his career and at crucial loci in his texts insofar as those loci are in the beginning of the texts, in order to establish a method which retroactively justifies said method on the ground of utility.

The fable is a transitive textual sphere that opens a horizon of textual temporality in which both the frame and the framed establish a complex relationship of justification and preparation; accordingly, the linear logic that one would assume a method to have is intrinsically linked to Descartes’s reoccupation of a ‘fabular logic’ . His biography is exemplary as the classical topoi of Humanist erudition have been before, his learning from the ‘book of nature’ has replaced a knowledge from reading, and his own experience and meditation is the pioneering result of an almost essayistic attempt at self-description that the Essais of Michel de Montaigne has produced before him . What Griffith only hints at is the temporal character of this employment. Fables appear every time that Descartes’s discourse becomes unstable, and they do so in the form of a promise. In anticipating the justification of their narration retroactively, on the basis of methodological success, the effective truth they contain is what legitimises their use in the first place.

Is Descartes’s fable, then, after all, mere embellishment? Does he misuse the genre name for didactive reasons, only to surpass this preliminary state later on in his text? Accordingly, is the “fable” nothing but a first step on the way towards method, simply a parergon for the real thing that will eventually result from the opening? The hierarchy of Descartes’s text, which will soon forget the specificity of this Ego in exchange for an application of its generalised abilities, seems to indicate it is. But the structure of ‘parergonality’, as described by Derrida, complicates the notion of a first step on the one hand and a full understanding on the other . As far as the fable is mere didactic introduction, it is supposed to dissolve once its real ergon is understood. But once the reader arrives at the all-encompassing relevance of the reduction of the Ego, it becomes clear that, in hindsight, the rite de passage is the Ergon, too; insofar as the Discours is showing us a transparent methodology, all steps on the way fulfil their purpose. This term, in its original Greek meaning of ‘the way towards’ or ‘the path beyond’ , is not fully independent of the linearity of the Discourse that starts with the fable to arrive elsewhere soon. In giving us an exemplary biography to retrace all the steps that have led our philosopher to the insight on which to base a wholly new way of scientific thinking—ultimately, the Cogito ergo sum that, though different from the rest of the world, is under no circumstances fabulist!—Descartes does not only rely on the assumed chronological succession of reading, from beginning to the middle and, ultimately, to the end. His text is as didactic as it is methodological, and the progression of understanding is one of the levels and genres of writing. His life, written down in broad sketches here, is a path that has to be followed step-by-step in order to arrive at the fundamental intuitive truth of the Ego. Accordingly, the text itself explicitly discusses the fables that were part of young René’s intellectual pathway:

‘Je ne laissais pas toutefois d’estimer les exercices auxquels on s’occupe dans les écoles. Je savais que les langues qu’on y apprend sont nécessaires pour l’intelligence des livres anciens; que la gentillesse des fables réveille l’esprit; que les actions mémorables des histoires le relèvent, et qu’étant lues avec discrétion elles aident à former le jugement; que la lecture de tous les bons livres est comme une conversation avec les plus honnêtes gens des siècles passés, qui en ont été les auteurs, et même une conversation étudiée en laquelle ils ne nous découvrent que les meilleures de leurs pensées […]’.

[I did not, however, cease to hold the school curriculum in esteem. I know that the Greek and Latin that are taught there are necessary for understanding the writings of the ancients; that fables stimulate the mind through their charm; that the memorable deeds recorded in histories uplift it, and they help form our judgement when read in a discerning way; that reading good books is like engaging in conversation with the most cultivated minds of past centuries who had composed them, or rather, taking part in a well-conducted dialogue in which such minds reveal to us only the best of their thoughts (…)]

So, as in his own intellectual biography, the reader is part of a Bildungsroman that starts with the fable—a classical, pedagogical, and minor genre that nonetheless is capable of ‘stimulations of the mind’. But as the text itself succeeds, so does the reader in walking every step that this exemplary speculator has taken in order to arrive at the very end of his ‘way’. Although he has grown out of the scholastic knowledge of his youth, it is presented as part of the great intellectual movement that has led him where he is now—as the founder of a methodological system that he demonstrates to us, recommending it for imitation.

Framing his text as his life, the fable does precisely what it is supposed to do—it is a form that contains some higher moral or truth, and is narrated solely to carry a deeper meaning that otherwise would have remained untransparent. The ‘evidence’ in all its ‘clarity and distinction’ that awaits us at the end of the road have been present from the start, yet it is only after removing all irritating and unreliable layers that veil it that the fable is put to good use. In this understanding, fables are nothing but narrative frames that are told to reveal their instructive kernel; their fabulistic or fictious nature is legitimised only by the morals they convey.

In this respect, the use of fable in Descartes becomes suspicious; while fables such as the influential Fables of La Fontaine restrict their didactic value to the representation of moral knowledge in literary miniatures, Descartes can only implement them according to his scientific needs. Here, methods take over the position morals would have had. The structuring principle of his most famous texts, the Discours and the Meditations, depends not only on this reoccupation that limits the scope of the fable significantly and makes full use of its secondary and introductory position in the text.

In understanding this exchange of morals for methods, we might be able to understand why Mundus est fabula is not only a catchphrase to remind us of the doubtful operation of reduction depicted in the Meditations and the Discours; the method he was looking for must have been there all along, hidden below the abundance of the world that young René has consumed like a book. What all his educational endeavours were good for is nothing less than the consequential certainty of doubt; with the suspicious mind of the Ego, a first ‘evidence’ is discovered that has been there inside the story all along. The world of Descartes itself has been a frame in which the simplest and most irrefutable certainties await us, once we become able to read it – not towards a moral, as we have read the micronarratives of Antiquity, but as parts of the advancement on a way to discover the real meaning behind the affluent phenomena. If the world is a fable, we can expand this adaption of the genre name by examining its positive side; the world is a fabulation, but one that contains the essential truths we need to forget its protracted narrations and to engage with its real value.