Abstract

Petrarch (1304–1374) aimed to establish a transnational and transtemporal community that could bring together authors from different epochs and regions by imitating the idealised ancient Greek and Roman world, overcoming the supposedly obscure Middle Ages. The first part of this case study shows how Petrarch’s vernacular lyric poems ‘Rerum vulgarium fragmenta’ were employed to foster concrete “Gesellschaften” and give rise to diverse cultural communities through two commentaries on the RVF, composed in Naples in the 1470s. The second part of the study delves into Petrarch’s efforts to build community within the Latin dialogue ‘De remediis utriusque fortunae’, with particular emphasis on a sixteenth-century German print edition. The conclusion addresses the impact of Petrarch’s role in building communities during the early-modern period.

When Francis Petrarch (Petrarca, 1304–1374) received the laurel wreath, the symbol of the glory of ancient poets, in Rome in 1341, he claimed to inaugurate a new epoch based on the imitation of the idealised ancient Greek and Roman period, as successor to the supposedly dark Middle Ages, as he wrote in the Collatio laureationis (VI, 1–2), the speech he composed for the occasion (Petrarca 1975). This groundbreaking claim was characterised by the crucial establishment of a community, incorporating future scholars who would write literature according to Petrarch’s example of imitating the ancients (Coll. VIII, 2). In doing so, Petrarch presented himself as the initiator of a transtemporal and transnational movement, often called “humanism”, as a crucial part of the Renaissance .1For a recent account on Petrarch’s role beyond his self-presentation, see and other works cited in the bibliography. However, Petrarch’s oeuvre is not a coherent monolith. While he wrote most of his works in Latin, one of the languages of idealised antiquity alongside Greek, and explicitly imitated forms and genres of well-known ancient models, Petrarch also composed two works in the modern vernacular that did not present immediate ancient models: the Trionfi (Triumphs), an allegorical poem, and the Rerum vulgarium fragmenta.

The collection of vernacular lyric poems Rerum vulgarium fragmenta is the work that gave birth to the vernacular cultural movement called Petrarchism, which flourished throughout Europe between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This contribution will discuss the dynamic methods Petrarch employed to build community in the early-modern period through two case studies: first, we will examine Petrarch’s vernacular lyric collection Rerum vulgarium fragmenta (hereafter RVF) through a close reading of two commentaries written during the fifteenth century. We will then shift our focus to the Latin dialogue De remediis utriusque fortunae, Petrarch’s highly influential encyclopaedic work during the early modern period . Finally, we will present concluding remarks that shed light on Petrarch’s efforts to foster communities within the context of the reception of these two works.

1. Building a community based on a bestseller in the vernacular: “social poetry” and “collective identity performance” in Petrarch’s RVF

To delve into Petrarch’s community-building endeavours, we will begin by exploring the traditional opposition between ommunity (Gemeinschaft) and society (Gesellschaft) . Society is commonly understood as governed by rational ties rooted in utility, often manifested through political structures, while the concept of community carries a distinct value associated with abstract moral, ethical, and aesthetic ideals, often tinged with a nostalgic perspective (; see also ). However, this opposition is further nuanced by the types of communities identified by Frank Kelleter and Yvonne Albers (Community), and Stephen Brint . These include communities that exist “prior to” their society, ‘expressing nostalgic yearnings for supposedly lost forms of commonality’, as well as communities “above”, ‘invoking ideals of togetherness situated at a higher moral, spiritual or religious plane of existence’, or “beneath”, ‘naming, for example, local and temporary forms of association […] apart from state organisation […] such as colloquially assumed sub-cultural identities […] or impermanent networks’ . Additionally, we will consider the notion of local and dispersed friendship networks .

Moreover, it is worth noting that when network members lack face-to-face interaction, they form a virtual community that can be dispersed across both space and time . Therefore, this particular type of community can be seen as a transtemporal affiliation that brings together authors from different periods, aligning with Petrarch’s aspirations to build community around the laurel wreath in 1341. Before specifying how these categories will be reformulated in the context of the recent debate on lyric communities (; ), we will briefly describe Petrarch’s communities, as represented in the Rerum vulgarium fragmenta and the text corpus of the Quattrocento commentaries.

In spite of its seemingly dismissive title, ‘Fragments of Vernacular (or Common) Things’, which reflects Petrarch’s innovative approach to renovating ancient studies in the modern lyric genre and in a modern language, he dedicated himself to the RVF until his final years . The collection comprises 366 poems, primarily centred around the portrayal of the speaking ‘I’’s love for a woman named Laura, whose name also serves as a symbolic reference to Petrarch’s groundbreaking authorship, represented by the laurel crown. Within the collection, Petrarch depicts his community as a transnational and dispersed network of friends that transcends conventional societal structures (Gesellschaften), encompassing his patrons, the Colonna family (e.g., RVF 10), coeval artists like the painter Simone Martini (RVF 77–78), and other vernacular poems, like Sennuccio del Bene (RVF 108, 112 etc.). Additionally, the collection features political poems addressing the contemporary state of affairs in Italy, such as RVF 128, concerning the Avignonese Papacy, RVF 136–138, and religious poems like the concluding RVF 366 dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

Within the context of its diverse subject matter, Petrarch’s vernacular lyric emerged as a widely imitated model that fostered a transnational community throughout Europe in the sixteenth century. At the same, the RVF posed a challenge to its readers, who made various attempts to provide a coherent reading of Petrarch’s persona and speaking ‘I’, as portrayed in his work. These endeavours are evidenced by the extensive body of exegetical writings that emerged as early as the fifteenth century. During the fifteenth century, several commentaries were composed . Initially, four commentaries were composed in Milan in the first half of the century . However, currently, only the unfinished exegesis by Francesco Filelfo and a fragment of Guniforte Barzizza’s work have survived. Finally, two commentaries were composed in Naples in the 1470s (; ), and two others in northern Italy in the same years (; ).

When examining the Quattrocento commentaries, it is crucial to recognise that they were composed within courtly settings and often at the behest of a political patron. Consequently, these exegeses aimed to emphasise aspects of Petrarch’s text that were particularly relevant to the commentator’s Gesellschaft, or social community. Simultaneously, Petrarch’s poetry was filtered through the expectations of diverse cultural communities within and outside the court. This dynamic allowed the commentary to align partially with Petrarch’s strategy to forge a transregional virtual community. To explore how the commentaries related to Petrarch’s strategies to build community beyond a singular Gesellschaft, we will focus on the Neapolitan commentaries by Francesco Patrizi da Siena and Francesco Acciapaccia. Both exegetical works were composed in the same local community in the 1470s (; ), albeit with different perspectives. While Acciapaccia undertook the commentary as a personal study project in his spare time, Patrizi worked at the request of his patron, Alfonso Duke of Calabria, with the support of a team of humanists (; ). By comparing Patrizi’s and Acciapaccia’s work, we will initially examine how each commentary responds to the expectation of their Gesellschaft. Then, we will address how the commentators create distinct transregional virtual communities beyond the local political community.

To explore the social function of the commentaries on the RVF, it is worth briefly examining certain aspects of the reception of Petrarch’s vernacular poetry in the sixteenth century in order to gain insights that will be valuable for our analysis. Virginia Cox’s study The Social World of Italian Lyric, 1550–1600 describes “social poetry” as a ‘prominent development within the tradition of Italian lyric poetry in the later sixteenth century’ . The term “social poetry” is meant ‘to encompass both what is generally referred to as occasional verse (i.e. poetry relating to a particular occasion or event), and also other socially engaged verse forms such as correspondence verse’ . In investigating this phenomenon, Cox examines lyric collections produced in urban centres that ‘offer intriguing case studies of how literary activity served to build and solder local communities and project their identity outwards’ . Furthermore, Cox observes that social poetry can be:

aesthetic objects and “cultural gifts”, individual and collective identity performances, cultural and political commentaries—social poems can be all these things, and more. An interpretative method capable of doing justice to their complexity must be as eclectic as the objects it serves’.

To investigate how commentaries read Petrarch’s poetry as a “cultural gift” and “collective identity performance” for their communities, we can turn to Federica Pich’s Framing Verse with Prose: Virtual and Material Communities in the Lyric Paratext . Pich highlights how the paratexts create virtual communities that ‘identify personae who “speak” in the poems and hint at the context of their “speech act”, thus highlighting a multiplicity of textual voices that might otherwise go unnoticed’ . Moreover, a virtual community ‘also evokes and mirrors readers’ . We could add that readers also evoke and mirror authorial figures, as we will see. To summarise, building upon Virginia Cox’s framework, we define social poetry as a utilisation of the lyric genre to engage with a community. This poetry is published as both a cultural gift and a collective identity performance. The collective dimension of the performance can be further examined through Pich’s concept of virtual communities, which focusses on the personae that emerge from the poems when read within the context of their speech act, thus reflecting the readers themselves. Considering these categories, we will investigate the communities involved in Francesco Acciapaccia’s and Francesco Patrizi’s commentaries. Comparing the exegetical works, we will explore how Petrarch’s poetry is utilised to support a Gesellschaft through a dedication, in Patrizi’s commentary, or through the incorporation of local history within the exegesis, in Acciapaccia’s work. Additionally, we will compare the readings of the speech act in RVF 27 to investigate how the commentators address dispersed networks grounded on different beliefs and virtual communities.

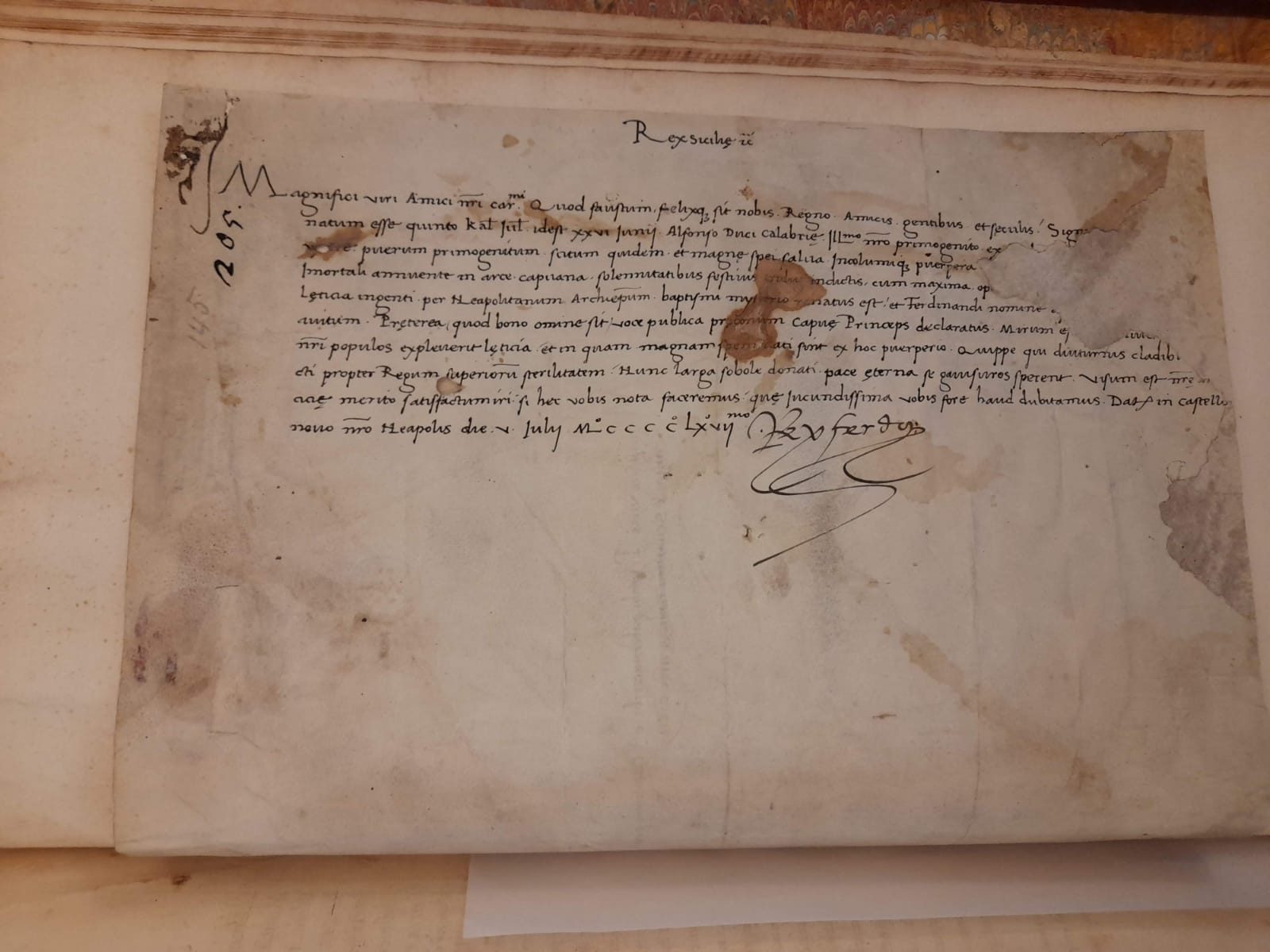

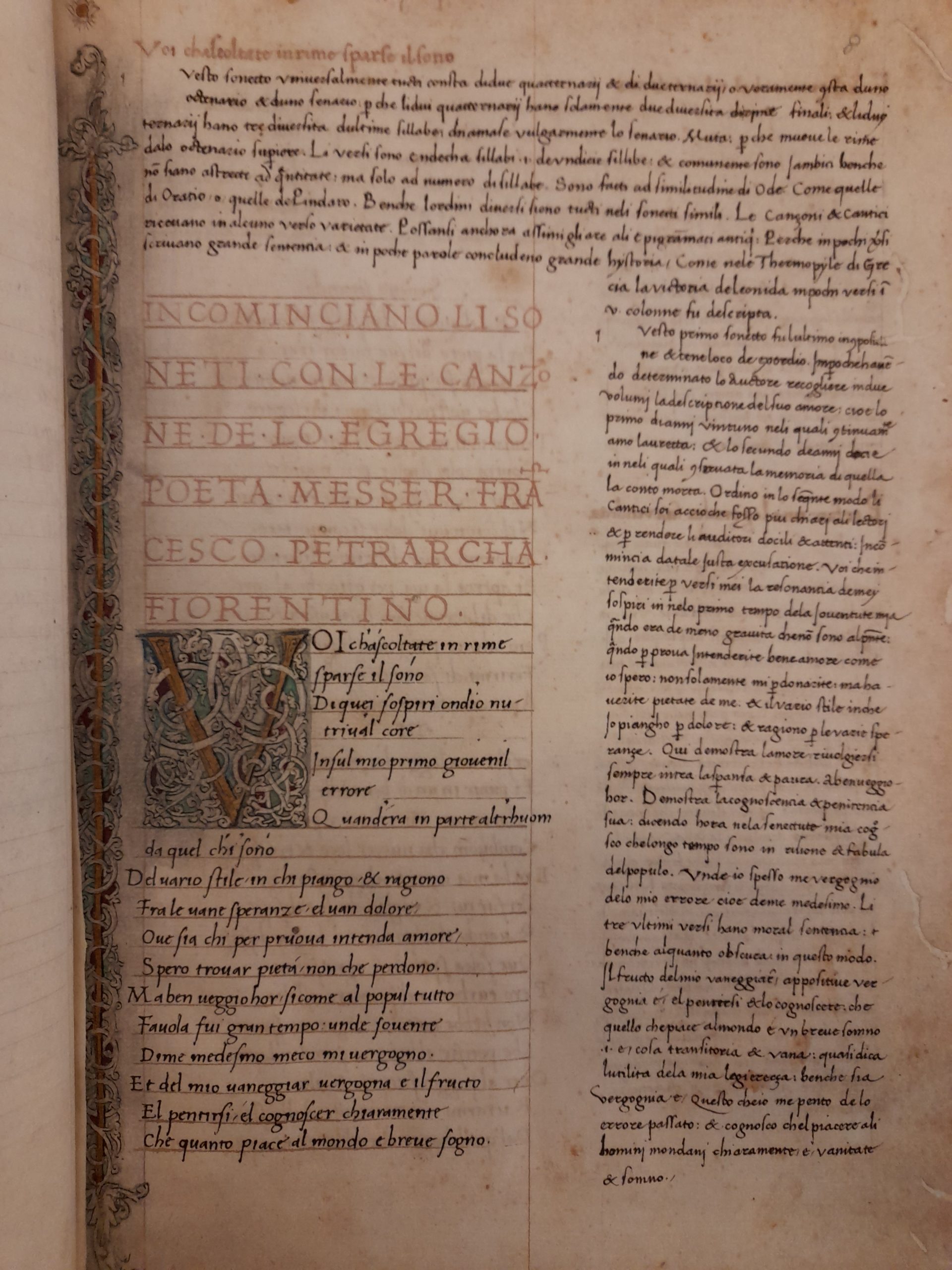

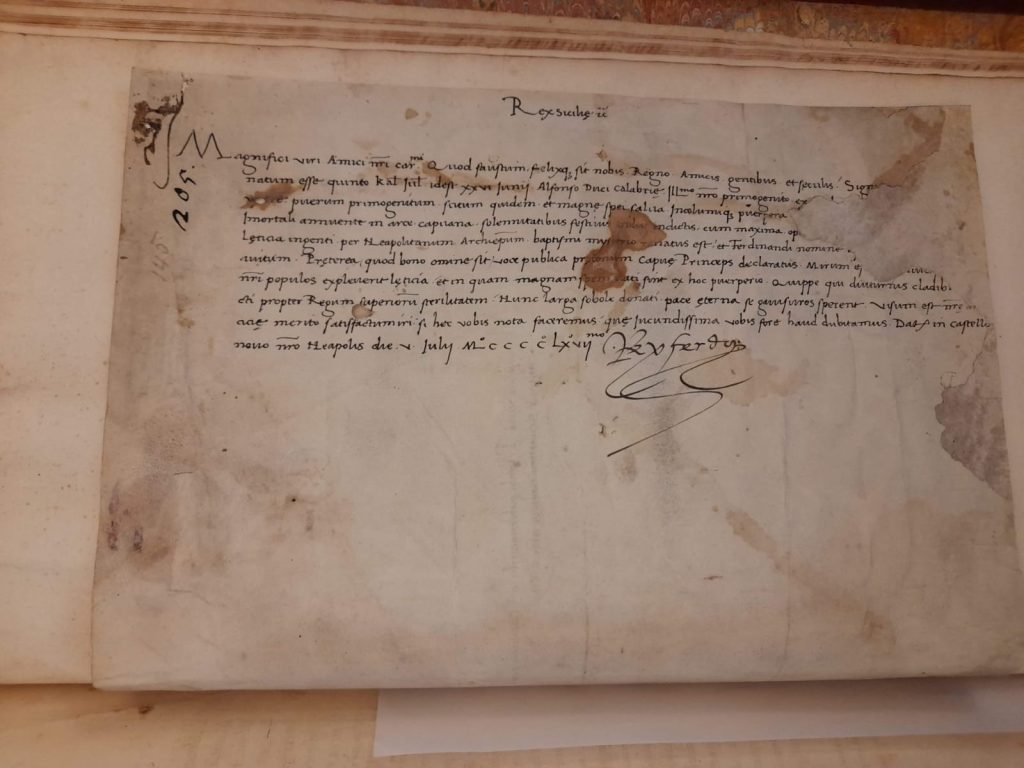

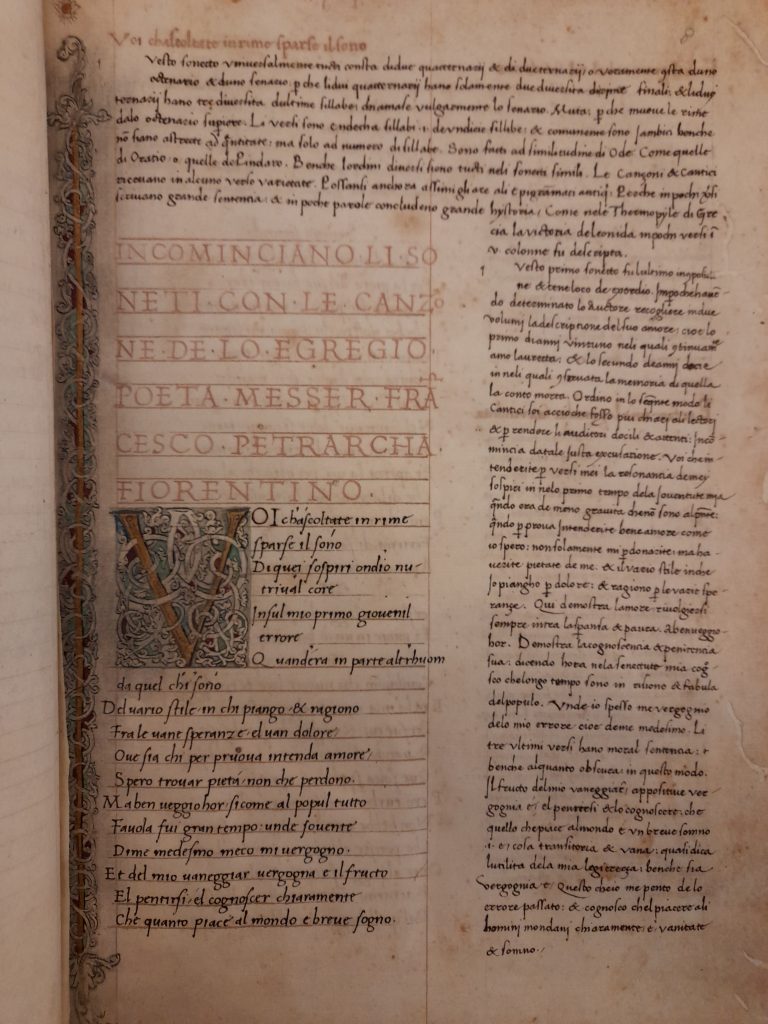

The two commentators, Patrizi and Acciapaccia, demonstrate different approaches in their treatment of Petrarch’s work, beginning with their Gesellschaft. One of the seven manuscripts carrying Patrizi’s commentary,2For further information regarding the other manuscripts containing Patrizi’s commentary, see the notes provided in Patrizi’s entry in the PERI (Petrarch Exegesis in Renaissance Italy) database: https://petrarch.mml.ox.ac.uk/manuscripts/patrizis-commentary-on-rvf-1-14-17-351-353-355-366-rome-biblioteca-casanatense-ms-50 (last access 25.05.23). This concrete manuscript is registered under https://petrarch.mml.ox.ac.uk/manuscripts/rvf-with-patrizis-commentary-on-rvf-1-354-and-index-london-british-library-additional (last access 25.07.24). the British Library MS ‘Additional 15654’, provides valuable insights into the exegesis, indicating that it was intended as a potential aesthetic gift, aligning with Cox’s notion . The manuscript includes a Latin letter that describes the circumstances of the composition (see Fig 1).3For the complete transcription of the letter and an examination of its context, see . It reveals that the manuscript was assembled for Alfonso of Aragon, Duke of Calabria and King of Naples. Upon examining the mise-en-page of the manuscript, we observe its elegant presentation. The text is carefully organised with ample spaces on the side, and it includes Petrarch’s poems, which are absent in Acciapaccia’s commentary. Significantly, the copyist left space at the beginning of each paragraph to insert decorated initials (see Fig 2). Although the manuscript remains incomplete,4For the reasons for the manuscript’s unfinished status, see . we can infer that its institutional destination suggests a higher regard for Petrarch’s vernacular poetry, which is likely emphasised in the commentary itself.

Fig. 1 RVF Manuscript with Patrizi’s Commentary (Colophon) / Fig 2. RVF Manuscript with Patrizi’s Commentary (f. 8r.) Source: From the British Library Collection: Additional 15654 f. 8r. https://petrarch.mml.ox.ac.uk/manuscripts/rvf-with-patrizis-commentary-on-rvf-1-354-and-index-london-british-library-additional

Before delving into the potential influence of this higher purpose of Patrizi’s work, it is important to examine the local aspect of Acciapaccia’s commentary.5Acciapaccia’s commentary is included in the manuscript Italien 1025 of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, online accessible: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b100326317 (last access on 25.07.24). In this study, Acciapaccia’s text is quoted from the partial digital edition, https://editions.mml.ox.ac.uk/editions/francisco-agiapagie/#about_text (last access on 25.07.24). While Patrizi primarily focusses on the historical dedicatees of the manuscript, Acciapaccia’s work takes a different approach by addressing the historical personae within the virtual community. In one particular instance, in RVF 27, Petrarch addresses a political and military commander titled ‘descendent of Carlo’, referring to Charlemagne.6The address is in the first verses: ‘Il successor di Karlo, che la chioma / co la corona del suo antiquo adorna’ (RVF 27, 1–2); [The successor of Charles who with the crown / of his ancestor now adorns his hair] . While modern scholarship identifies this figure as the French king Filippo VI (1293–1350) , Acciapaccia explicitly identifies him as Robert of Anjou, the former king of Naples (1277–1343).7‘Il soccessor di carlo: cioè Re Roberto che soccedecte al Re carlo in lo Reame di la gran Sicilia’ (Acciapaccia f. 23r). [The successor of Carlo: namely King Robert who followed King Carlo in the Kingdom of Sicily]. Translation are the authors’, unless stated otherwise. It is important to note that Robert was not Charlemagne’s son but rather the son of Charles II. Through this interpretation, Acciapaccia effectively incorporates the institutional history of the Gesellschaft into Petrarch’s work, thereby endowing his community with a literary legacy and a shared cultural memory.

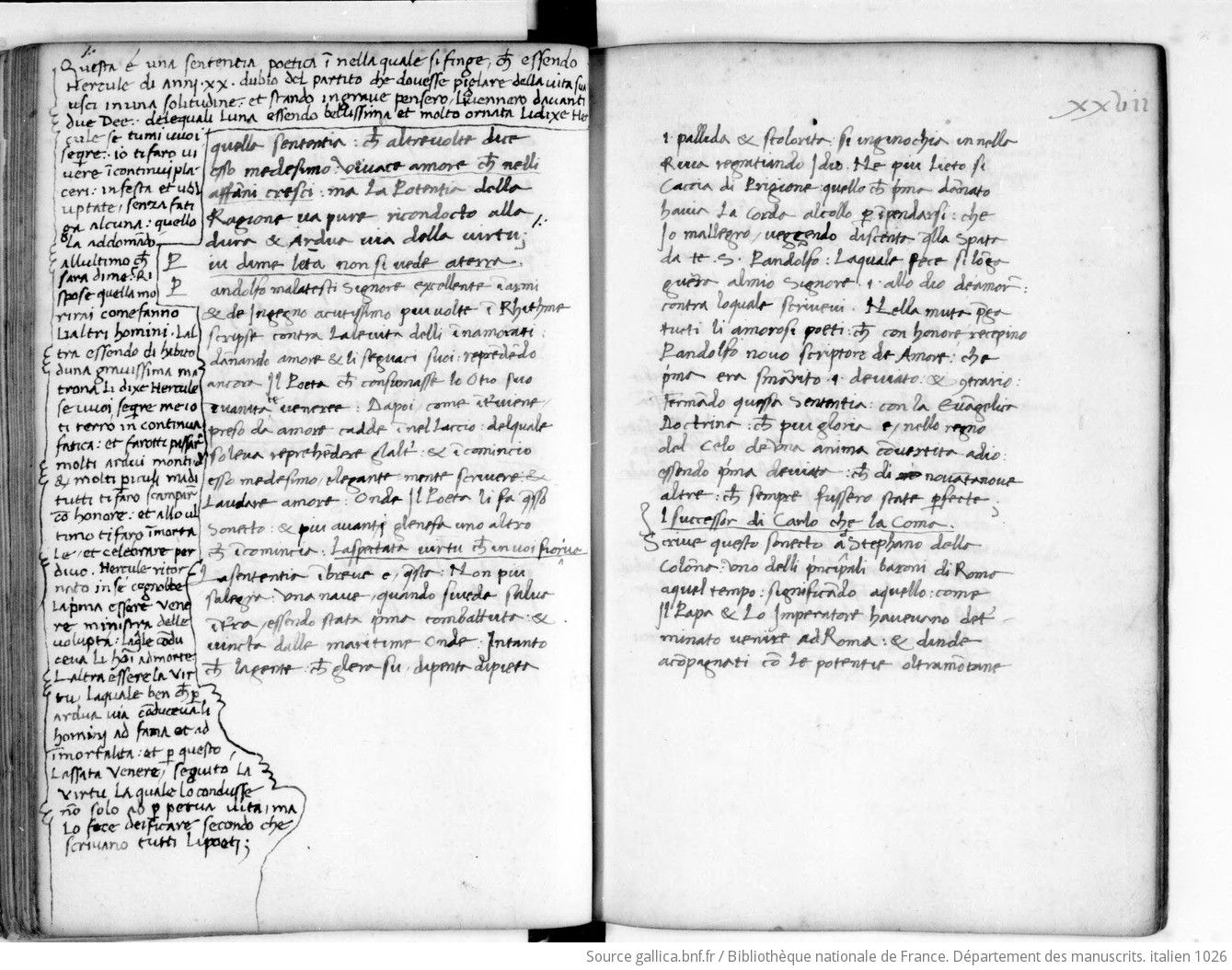

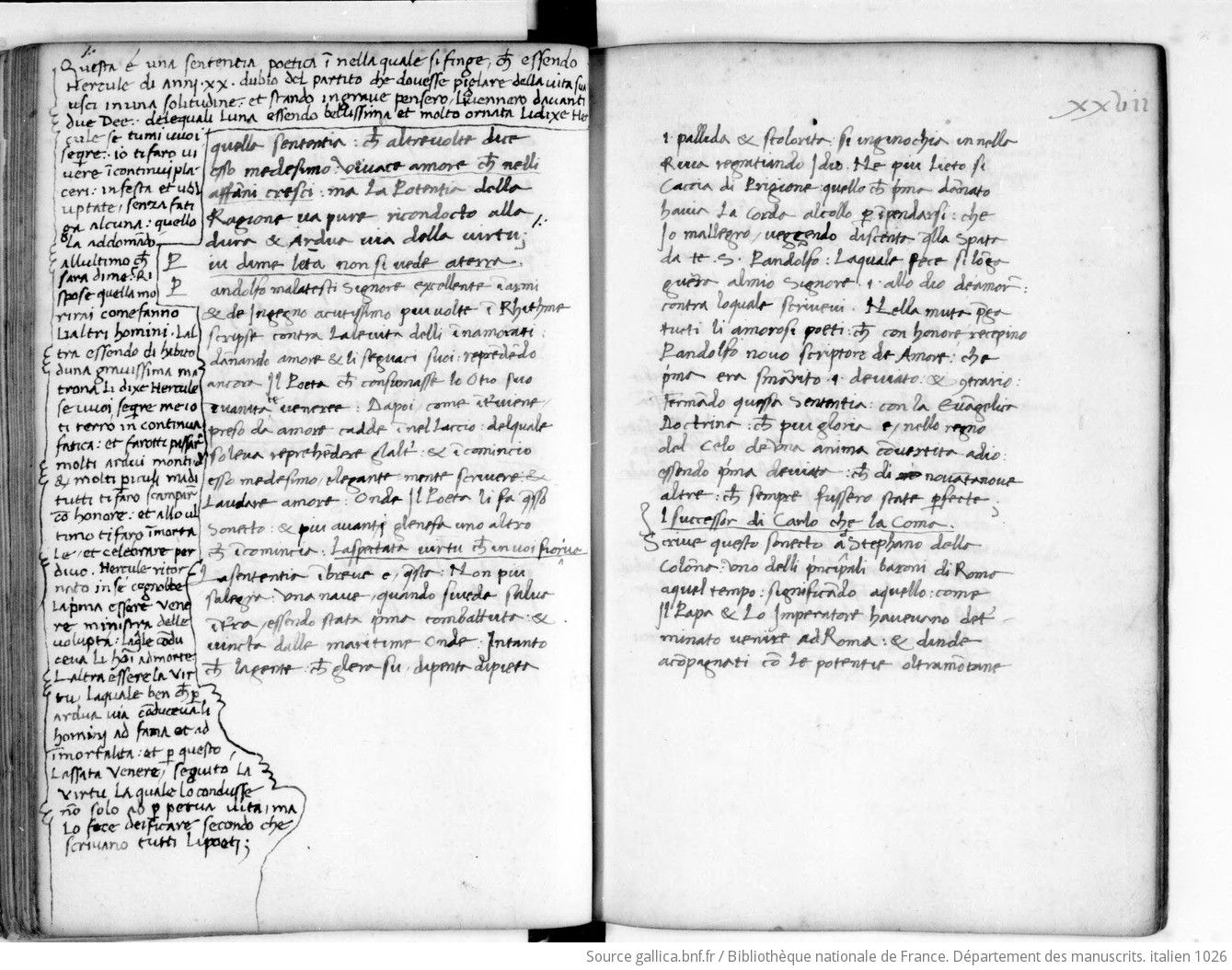

Shifting our focus to the Gemeinschaften involved, RVF 25 portrays Petrarch’s speaking ‘I’ addressing a friend and explaining that love cries because the fellow is no longer in love. After Petrarch’s prayers to God, the friend has discovered the path of virtue.8‘Amor piangeva, et io con lui talvolta, / dal qual miei passi non fur mai lontani, / mirando per gli effecti acerbi et strani / l’anima vostra dei suoi nodi sciolta. / Or ch’al dritto camin l’à Dio rivolta, / col cor levando al cielo ambe le mani / ringratio lui che’ giusti preghi humani / benignamente, sua mercede, ascolta’ (RVF 25, 1–8). [Love at times would weep, and I, with him / from whom I never kept too far a distance, / would weep to see the strong and strange effects / that have released your soul tied in his knots; / now that God has returned it to the right path / with heart raised to the heavens and both hands, / I give my thanks to Him who in His mercy / so kindly understands just prayers of me] . However, the nature of this path of virtue becomes a subject of interpretation. Acciapaccia’s commentary suggests that the right path to virtue is actually the path of love and, according to his reading, Petrarch is pleased that the man fell in love again.9‘Dio Signore ha reducta l’anima di quello amico al dricto camino, cioè a la vita amorosa in la quale era da prima stata esso Petrarca col core et co le mani al cielo ringraciava Dio Signore humilmente, perché havea exauditi li prieghi soi benegnamente. É segnio che lo Petrarca, vedendo quel caro compagno havere lasciato per disdegno o per altro la strada d’amore, havea pregato Dio Signore che lo facesse tornare a la dritta via d’amore’ (Acciapaccia f. 22r). [God turned the soul of that friend to the right path, namely to the love life in which Petrarch himself was. Petrarch thanked God humbly with his heart and hands towards the sky because God benignly accomplished his prayers. This means that Petrarch prayed to God to bring his friend back to the right path of love, seeing the friend left it for disdain or other reasons]. In contrast, Patrizi’s interpretation takes a different approach. According to his exegesis, Petrarch’s friend fell in love with a cruel woman who nearly brought him to his demise. Consequently, Petrarch implored God to guide his friend back onto the arduous path of virtue, resisting the vanities of love.10‘Essendo in questi pianti venne nove che voi eravate sanato e che in tutto pentuto dello errore, veramente disamorato. La qual cosa sentendo, rengratiò dio che per sua merzè ha exauditi li nostri preghi e ha rivolta l’anima vostra allo dritto camino, cioè alla virtù, lassando el vano amore’ (Patrizi f. 23r). [Being in these cries, news came that you were healed and completely repentant of your error, truly unloved. Hearing this, (Petrarch) thanked God, who by his mercies heard our prayers, and turned your soul to the right path, that is to virtue, leaving vain love]. Patrizi’s text is quoted according to the manuscript Italien 1026, Bibliothéque Nationale de France. Moreover, the manuscript Italien 1026 of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France provides further insight into Patrizi’s exegesis, highlighting his emphasis on the mythological aspects of Petrarch’s work. This emphasis is evident through the gloss on the side that connects the arduous path with a detailed exposition of the myth of Hercules, occupying a significant space within the manuscript and rivalling the commentary on the text itself.

In exploring the comparison between Patrizi’s and Acciapaccia’s commentary, it is pertinent to consider again the relationship between Gesellschaft and Gemeinschaft. One notable aspect is how Petrarch’s text gives rise to cultural communities that intersect with the local institutional community. This is exemplified by the mention of Alfonso of Aragon, Duke of Calabria and King of Naples, as the dedicatee of the work in Patrizi’s letter of dedication. Similarly, Acciapaccia refers to King Robert as a persona, a historical addressee of Petrarch’s poem . These instances demonstrate the incorporation of the commentators’ own Gesellschaft within Petrarch’s work, reflecting Virginia Cox’s notion of social poetry as ‘literary activity served to build and solder local communities and project their identity outwards’ .

Within the realm of the Gemeinschaften, commentaries create various communities “beneath”, “above”, and “prior to” the local community . This becomes evident exploring the different interpretations aiming to ‘identify personae who “speak” in the poems and hint at the context of their “speech act”’, as in the case of Petrarch’s encouragement to his addressee: the interpretation of Petrarch’s dispersed network in the poem as composed by virtuous or enamoured friends reflects the constitution of the community surrounding the commentary itself . As for the persona who speaks in the poem, Acciapaccia portrays a vernacular Petrarch who is deeply in love and engages in a sonnet exchange with a friend to discuss their emotions. Acciapaccia’s reading suggests that Petrarch’s path of virtue is actually embodied by love and that Petrarch encourages his friend to embrace it again. For Acciapaccia, this particular conception of love becomes a pivotal element in Petrarch’s and his own efforts at building community. It forms a dispersed network of friends as a community “below” their Gesellschaften, united by the composition of love sonnets.

In contrast, Patrizi presents a different perspective by identifying the right path of virtue as being devoid of love. This identification leads to Petrarch’s figure as a Christian poet who is superior to love, despite the context of his vernacular love lyric. Petrarch prays to God, seeking strength for his friends to resist the temptations of love. This portrayal of Petrarch as a Christian figure can be understood within the broader context of Patrizi’s commentary, which serves as a ‘cultural gift’ and a ‘collective identity performance’ for his Gesellschaft. The commentary aims to establish a community “above” the Gesellschaft, using Petrarch’s dispersed moral network of friends as an ideal model. However, it is important to notice that Patrizi’s community “above” and Acciapaccia’s community “below” are not the only communities suggested in these passages. We must also consider the level of the virtual community with its transtemporal formations.

When examining the aspect of the virtual community, we can observe the transtemporal elements that both commentaries sought to incorporate. Acciapaccia, on the one hand, highlights in the RVF the narrative centred around Petrarch’s first-person speaker and his beloved woman, Laura, turning them into the protagonists of a love story influenced by the conventions of medieval courtly poetry. On the other hand, in the commentary on RVF 25, Patrizi seeks to minimise the sentimental aspect and instead emphasises the ancient elements in Petrarch’s poetry. As evident from the erudite excursus about the arduous path, Patrizi consistently highlights elements from the idealised ancient world, which occupy a significant portion of the commentary, sometimes finding almost more space than the commentary on the poem itself.

In conclusion, Cox’s characterisation of social poetry as both aesthetic objects and cultural gifts resonates with the commentaries of Patrizi and Acciapaccia. These commentators actively insert their Gesellschaft within Petrarch’s work, in Patrizi’s case through, for example, the dedication in the manuscript BL MS ‘Additional 15654’ or in Acciapaccia’s case through the identification of King Robert of Naples in RVF 27. Moreover, social poetry also encompasses ‘individual and collective identity performances, cultural and political’ . This is evident in Pich’s analysis of the identification of the ‘personae who “speak” in the poems’ and ‘the context of their “speech act”’ . Patrizi and Acciapaccia offer contrasting interpretations of Petrarch’s speaking ‘I’ and his addressee, representing either a vernacular love community “below”, highlighting the transtemporal courtly medieval element or a Christian erudite community “above”, highlighting the ancient and mythological element, within Petrarch’s work. These interpretations reflect the communities they performatively sought to establish around Petrarch’s Rerum vulgarium fragmenta. However, this only represents a portion of the broader discourse about the dynamics surrounding Petrarch’s persona and work in the early modern period.

2. Building a community based on an international bestseller in Latin: Petrarch’s De remediis

The dynamics that Francesco Petrarch’s person and his texts generated in the Early Modern period in terms of fostering cultural and ideological community have had a considerable impact on the history of the reception of Petrarchism in Italy and internationally. This can be seen very clearly in Petrarch’s internationally most successful text, De remediis utriusque fortune, which Petrarch himself conceived as a ‘bestseller for humankind’ (see ). The question of what kinds of communities have been constituted by Petrarch’s texts and their reception has been relatively little studied so far. As for De remediis, the first question to be asked here is which concepts of community can be particularly helpful in explaining what is going on in this text and in its tradition. For this purpose, one can profitably fall back on the typological categories of the concept of community developed by Steven Brint .

Petrarch’s De remediis is an imposing opus comprised of 253 dialogues between Ratio, or reason personified, and the four passions of the soul (passiones animi) according to the Stoic tradition: Pain (Dolor), Fear (Metus), Joy (Gaudium), and Hope (Spes). Containing 122 dialogues on ‘good fortune’, the first of its two books addresses the human response to the positive aspects of life, while the 131 dialogues on ‘bad fortune’ that make up the second book offer advice on how negative experiences can be overcome. In the 1350s and 1360s, Petrarch wrote a good part of the text in courtly surroundings, namely in the service of the Visconti in Milan (for the genesis of the text cf. , with rich bibliography). However, in his preface to the first book, Petrarch directly addresses not a representative of the Visconti dynasty, but rather his old friend Azzo da Correggio, a despotical politician whom Petrarch’s preface stylises as an ideal recipient of the text. Petrarch emphasises how Azzo had experienced precisely those vicissitudes of fate that are discussed in the text which is to follow—and had been able to withstand them (Pref. 1; §§ 5, 12–15). Petrarch offers his friend the text of De remediis as a help in future difficult and challenging situations of life. This text would serve him as a medicine for his soul, concentrated in capsules, so to speak. In De remediis, the results of the author’s extensive readings are presented in a handy form: for Azzo, this should have the advantage of being able to draw immediate benefit from Petrarch’s moral-philosophical reflections without having to read himself all the ancient and medieval texts which Petrarch had painstakingly compiled (Pref. 1; §§ 6, 11).

Towards Azzo, but also towards all readers of the text, Petrarch acts as a mediator who shares the results of his work with the community of his audience and thus, in a gesture typical of the supposed ‘father of humanism’, makes the knowledge of the lost commonalities of antiquity, a huge cultural community “prior to” the Early Modern period, available again. In his project to reform the early-modern spectrum of knowledge by approaching the culture of antiquity (see ), Petrarch always suggests the effect of an immediacy of contact with the communities of the past (a certain paradox, since he also constantly emphasises their great temporal distance). This is most clearly discernable in the twenty-fourth and last book of his collection of letters entitled Familiares, which contains Petrarch’s letters to the great authors of antiquity, such as Cicero, Virgil, and Seneca.

As can be seen in the relationship that Petrarch’s voice establishes with the addressee Azzo, Petrarch the mediator is ideologically always located “above” the conditions that characterise the present time, a hierarchical top position that Petrarch’s texts justify primarily in terms of moral philosophy. In these texts, this also implies a ubiquitous opposition of humanist culture and community against the model of ‘strongly mediated, highly formalised, or abstractly depersonalised forms of association’ , namely against the culture of scholasticism, which Petrarch dismisses as outdated.

Both the genesis of the text in the Visconti environment and the apostrophes to Azzo prove, first of all, Petrarch’s effort to integrate De remediis as a kind of communicative tool into his personal network with people he had physically encountered across time and again in his life. In Brint’s words, the primary pragmatic dimension of De remediis thus is a ‘local friendship network’: this, of course, does not simply exist on its own, but is always being constructed by Petrarch and others, and De remediis contributes to this construction as much as it officially presupposes it as already existing.

The members of Petrarch’s local friendship networks are integrated into social structures and act as their representatives. We are therefore dealing with existing phenomena of Gesellschaft in the context of which Petrarch enacts his social networking. But one can hardly say that Petrarch’s intention was simply to activate parts of the structures of Gesellschaft for his communicative purposes. Rather, Gesellschaft is only the indispensable basis departing from which Petrarch develops a Gemeinschaft that goes beyond a local friendship network. In the official pragmatic dimension of the text, De remediis is initially addressed to elitist groups of recipients. Certainly the local friendship networks we have just described are somewhat elitist, and this applies, as well, to their intended expansion. Petrarch (not only in De remediis, but also through many of his other texts, especially his collections of letters, the already mentioned Familiares and the Seniles) wants to transform the ‘geographically’ (Brint) based local friendship networks into choice-based elective communities and then expand these elective communities transregionally (towards the various forms of networks and communities discussed by Brint, which are ‘dispersed in space’).

Petrarch’s strategies for publishing De remediis seem to have been vigorously aimed at community building. The author himself actively wanted to ensure the broad reception of his text. It is anything but usual for Petrarch to have completed and revised De remediis comparatively quickly and then immediately published it himself. In a letter to Tommaso del Garbo in November 1367, Petrarch expressed his satisfaction that De remediis had been well received by various important readers (Seniles 8.3.60 ‘eo tamen michi [liber De remediis] probatior factus est quo illum quibusdam magnis ingeniis gratum valde et optatum sensi’ [Nevertheless, the book De remediis is all the more dear to my heart as I have learned that it has met with great interest and goodwill from certain high-ranking personalities]). By this stage, the text had become familiar enough that John of Neumarkt, as chancellor to Emperor Charles IV, wrote to Petrarch in March 1362 urging him to accept the emperor’s invitation to Prague and bring De remediis with him: ‘Veniat, queso, tecum liber ille qui loquitur utriusque fortune remedium’ [And you should please have the book with you that talks about the remedies for both kinds of fortune.] (cf. ).

Certainly, one of Petrarch’s aims was to involve eminent persons on an international level in a form of ideologically-based ‘dispersed friendship networks’. The members of such networks are per se only conceivable as socially established, eminent persons (members of groups at the top of Gesellschaft): these could be persons who had outstanding influence in the sphere of political and social power as well as persons of intellectual excellence, such as humanistic intellectuals, culturally active dignitaries of the church, or the like.

Due to the dedication to Azzo, but also in view of some of the themes dealt with in the dialogues of De remediis, it has repeatedly been claimed that the intended audience of De remediis was limited to elitist circles of the mighty. Pertinent dialogues might be listed in no small number. They carry titles such as ‘On Public Office’, ‘On Great Wealth’, ‘On a Treasure Find’, ‘On Owning Gold Mines’, ‘On Friendship with Kings’, ‘On Power’, ‘On Fame’, ‘About a Powerful Army’. However, it would be wrong to draw a one-dimensional conclusion about the intended audience of the text from the treatment of such topics. Because in this case, if we look at, for instance, a dialogue like ‘On the Papacy’, in which the affect Joy is elated at having just been elected Pope, the intended audience of De Remediis would be limited to the current Pope. If we take a closer look, we immediately notice that in De remediis absolutely all kinds of situations that might occur in human life are treated. Not only situations that affect rich and powerful people, but also issues such as physical deformity, weakness, ugliness, low birth, dishonour, bondage, poverty and economic difficulties, failure in public and social life, various kinds of adversity, and threats to human existence. This gives the initial impression that with De remediis, Petrarch as a mediator of human life problems is generally addressing ‘humankind’ as the community of readers (hence the title of ).

In order to be able to better describe the establishment of community that De remediis aims to achieve, we must briefly examine the argumentative structure of these dialogues. Petrarch’s Latin original has frequently been interpreted as a generic late-medieval dialogue between teacher and pupil. Such an interpretation often goes hand-in-hand with the belief that in the dialogues a clearly superior Ratio has the final word and triumphs over the verbally deficient Affects, whose utterances amount to nothing more than a mindless repetition of paltry and obtuse emotional impressions. When approached from such a vantage point, Petrarch’s dialogic text becomes a monologue, which, under the guise of rational moral philosophy, offers a conservative and backwards-looking attempt to curb and contain a worldview tinged with emotion and governed by the passions. Few scholars have asked themselves to what kind of medieval audience such a ‘dialogic monologue’ might have been addressed. But this would be the wrong question to ask anyway, as the relationship between Ratio and the Affects in De remediis is, in fact, highly complex and multi-faceted (cf. generally and, for a concrete example, ). For one, Ratio is really quite inconsistent and frequently contradicts herself. She is openly emotional and does not always prevail rhetorically over the four passiones animi, whose personifications are much more than mere discursive “dummies”. Upon closer inspection, it also becomes clear that Petrarch’s authorial voice is far from easy to pinpoint. By no means does the “Petrarch” implicit in the text unequivocally side with Ratio, and neither do the Affects receive a uniformly negative treatment in all the dialogues. As a result, De remediis acquires a polyvalent and ambiguous profile. The strong emotive tone of the dialogues is, moreover, an indication that the reading community targeted by Petrarch is also constituted through affective bonds (see ).

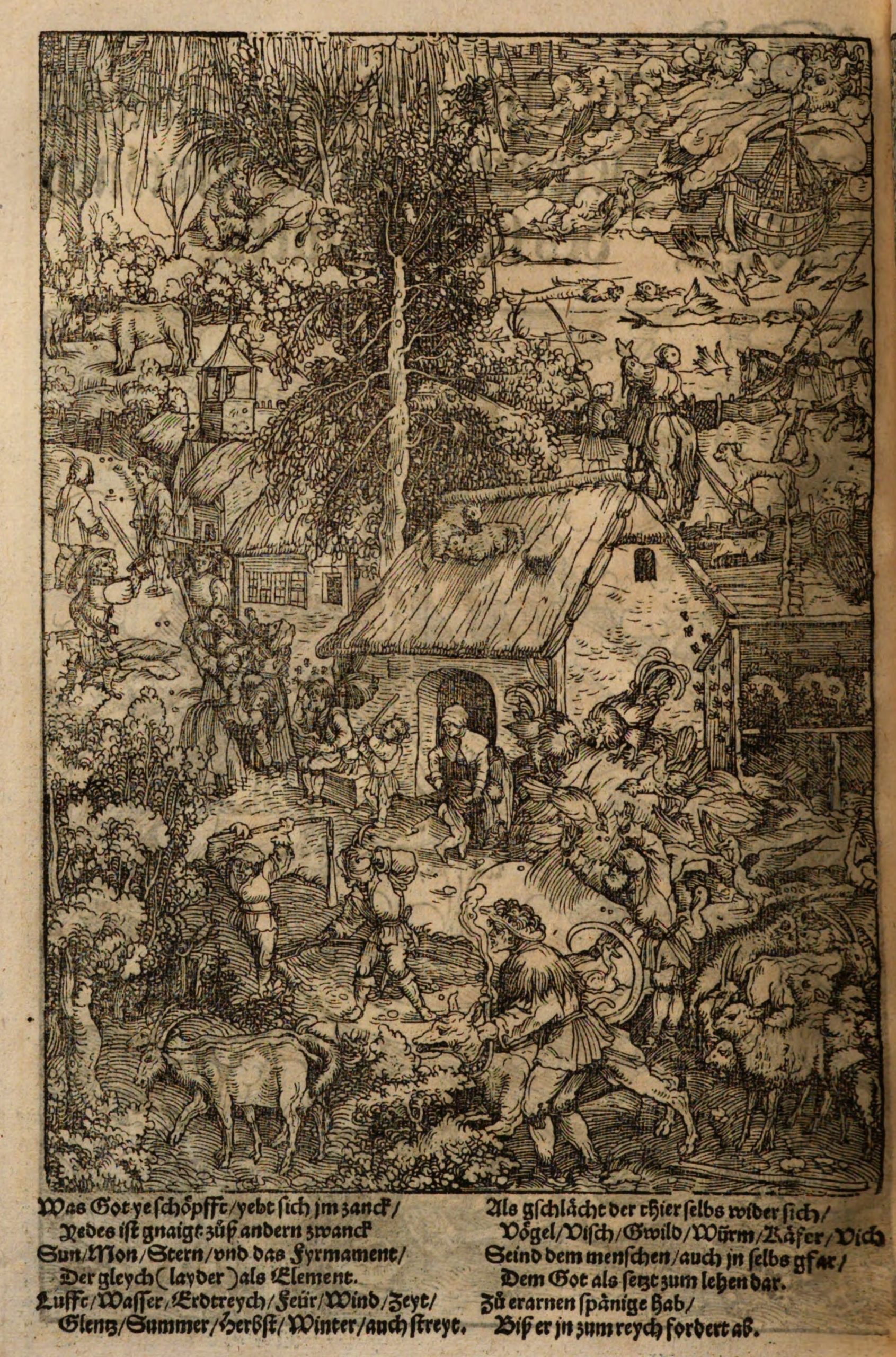

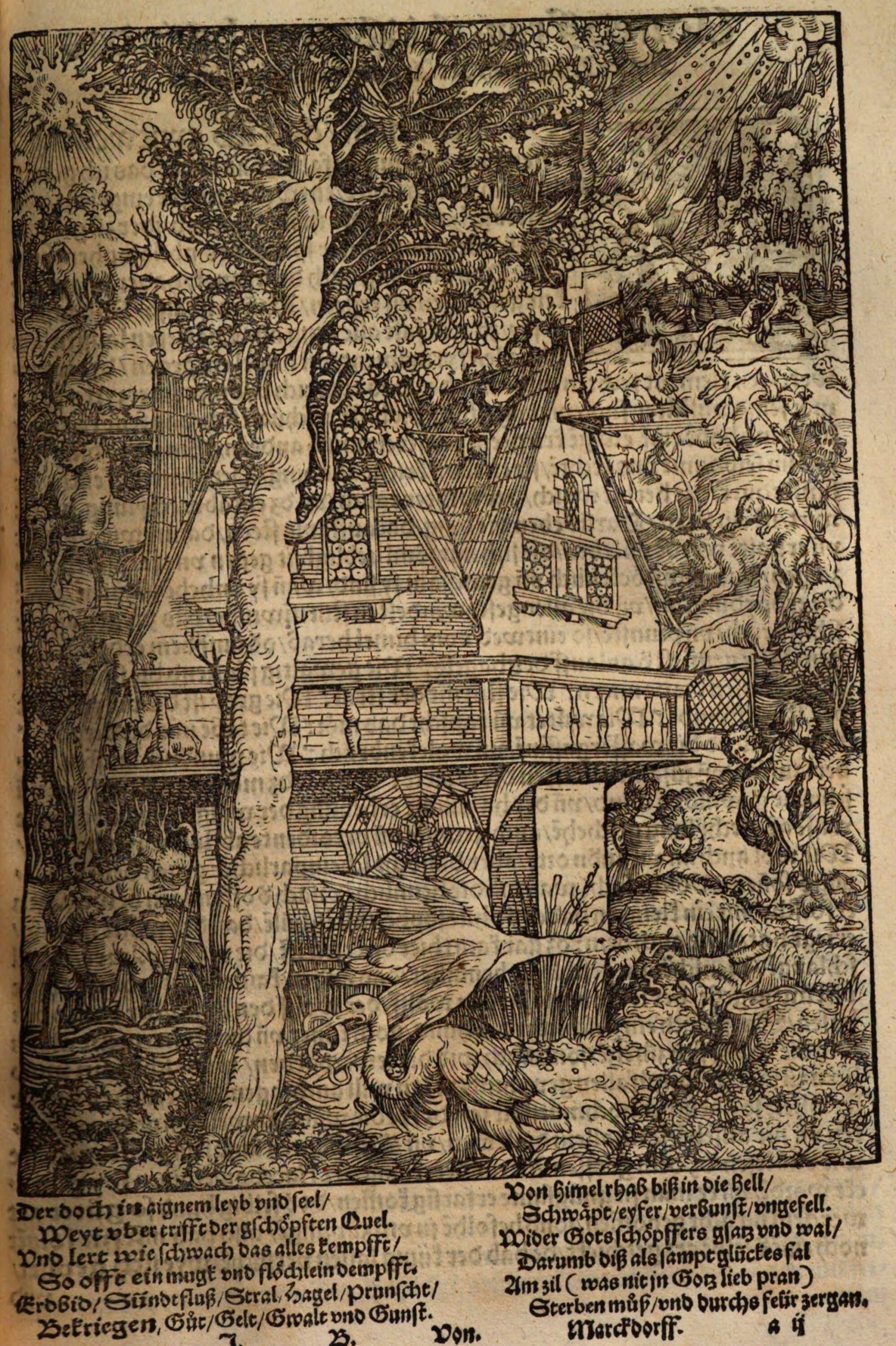

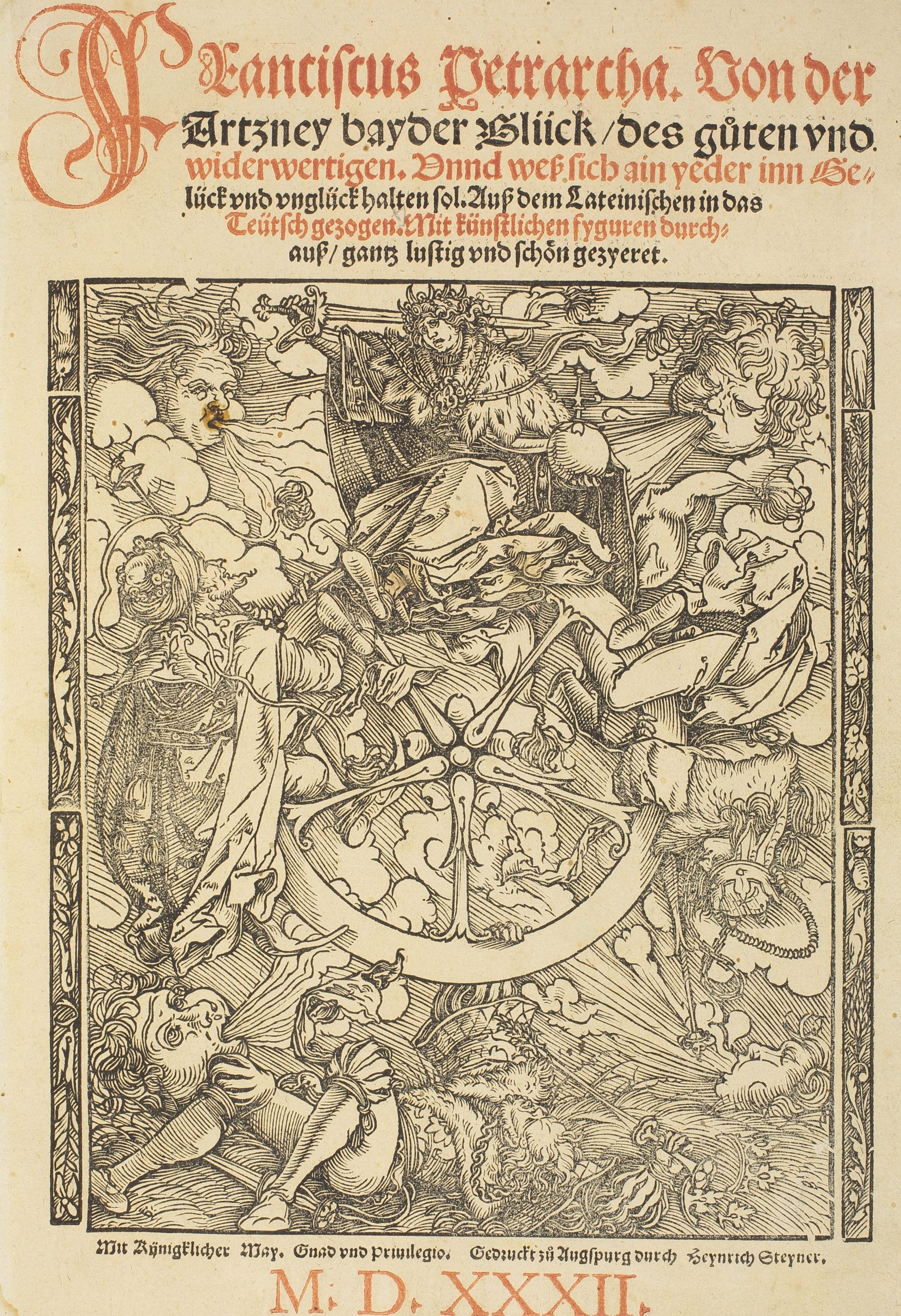

Politics involving powerful people certainly is not a subject that Petrarch would be primarily interested in when he discusses ‘political’ topics. This is also to be seen in the 1532 German illustrated edition of De remediis, entitled Von der Artzney bayder Glück…, which is probably the best-studied object in the entire history of the reception of De remediis (see bibliography in ). It was published in Augsburg by the publisher Steyner, and for each dialogue it has a woodcut by an outstanding anonymous artist who is known as the Petrarch Master (Petrarca-Meister). Here, too, just like in Petrarch’s own text, every political and social message is always built on a much more fundamental moral-philosophical basis, a basis that then applies to all people and not just to the supposedly powerful. Here is a quick look at the title page of the 1532 edition (see Fig 4). It appears at first glance to set the well-known motif of the Wheel of Fortune in an overtly political context. If this image simply portrayed the volatile dynamics of rulership, with kings (including an Ottoman) attempting to achieve and maintain power only to fail and be destroyed, then the book’s message would be a critique of the inherent instability of monarchy, of constantly changing international power constellations, and, quite likely, also of the stupidity and cruelty of potentates. But while the Wheel of Fortune does serve the purpose of illustrating social and political conditions that are by no means unimportant and in some cases highly topical, like the allusion to the ‘Turkish menace’, the Artzney’s main concern lies with the various causes and moral-philosophical backgrounds of these conditions, and this agenda is clearly represented by its frontispiece. What makes the image of the changing fortunes of earthly rulers so dynamic and emphasises its sense of universal disorder are the contrary winds which blow from the four corners and serve as pictorial representations of the passiones animi. Playing a crucial role in De remediis, these passions of the soul also appear elsewhere in Petrarch’s writing, for example in his Secretum meum, where they are described by the character of Franciscus as ‘four conflicting winds’ that destroy ‘the tranquility of men’s minds’ (1.15.3). In the preface to the second book of De remediis, the passiones animi are likewise referred to as a ‘storm’ (tempestas) (§35). If humans fail to distance themselves self-reflexively from the winds of Joy, Hope, Pain, and Fear, they are blown off course in their feelings, thoughts, and actions, which is the root cause of the chaos of human existence. For both Petrarch and the Petrarch Master, the political message highlighting the volatility of rulership is only one aspect among many within the much more fundamental issue of cosmic ordo vs. universal disorder.

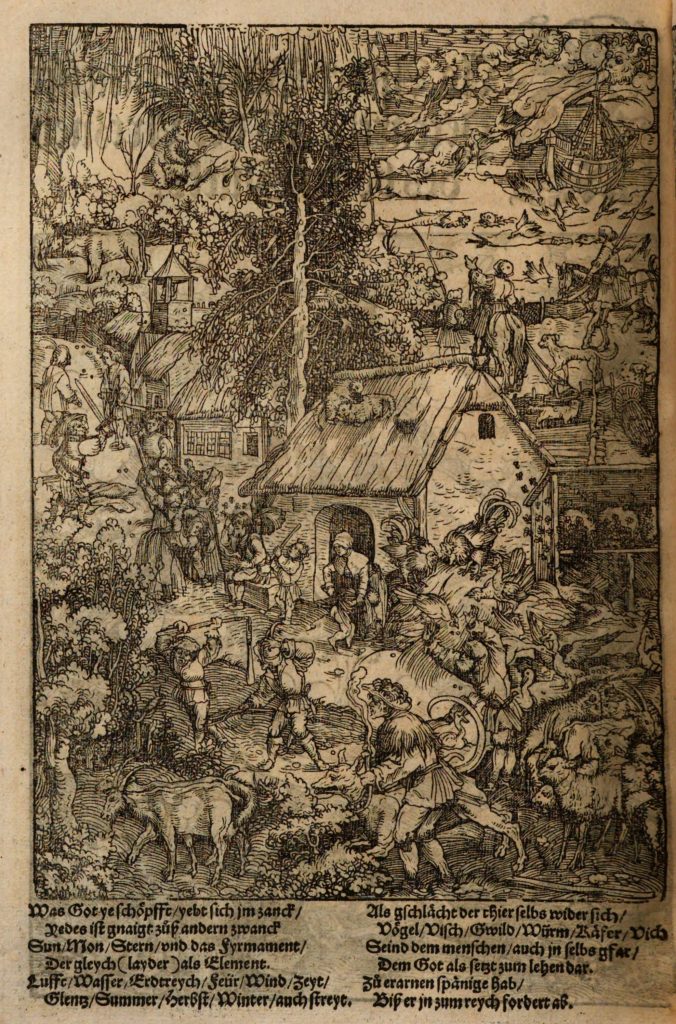

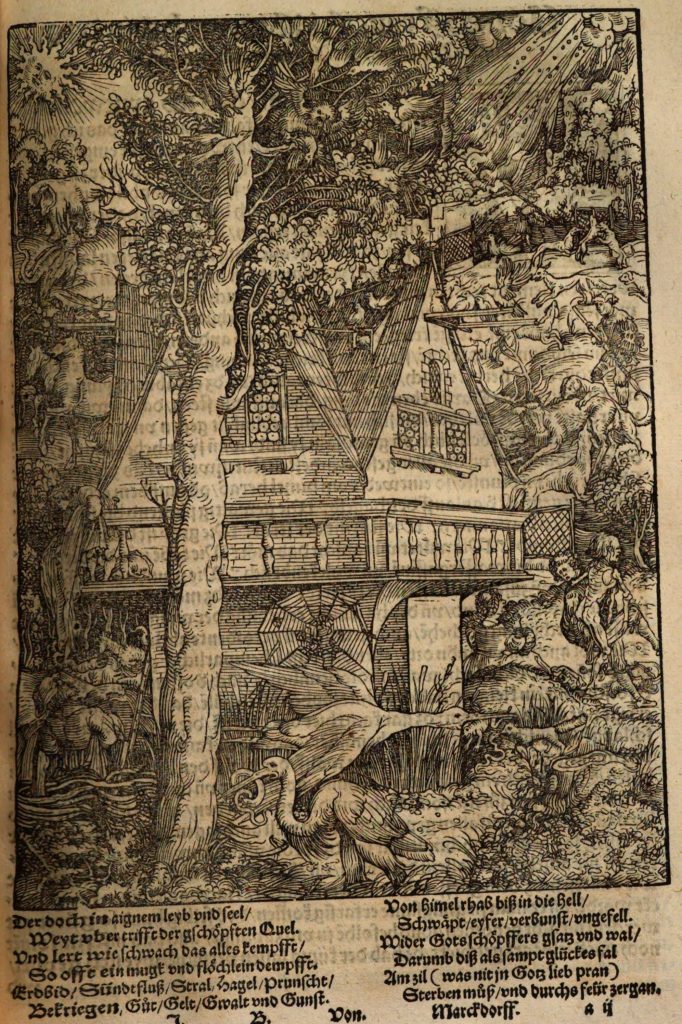

Especially in his preface to the second book on ‘bad fortune’, Petrarch extends his observations on the afflictions of the human condition to include nature and ultimately the entire cosmos. Here, too, the Petrarch Master follows suit. The portrayal of strife, enmity, and destruction found in his two accompanying woodcuts (nos. 186 and 187 Musper) bears a close resemblance to Petrarch’s text. While one of the widely discussed images uses a peasant’s rustic dwelling as a backdrop, the other features a stately and “patrician” domicile. Scholars writing from a Marxist perspective (which is, in terms of sheer quantity, very considerable, due to a quite long series of publications on the Petrarch Master from the former German Democratic Republic) have interpreted these scenes as a pointed critique of social hierarchies. From this perspective, the Petrarch Master would, with his illustrations for De remediis, very precisely refer to certain conditions in Gesellschaft in order to side with the community of all underprivileged social strata. What the two woodcuts are meant to demonstrate, however, is rather that the ever-present and all-encompassing danger of disorder threatens all humans, whether they be peasants or members of the wealthy elite, which is precisely why the Artzney exhorts all of its readers to concern themselves with it. In other words, the two woodcuts appear to convey a message that is perfectly compatible with the sweeping agenda and broad circle of addressees that Petrarch outlines in the preface to the second book of his De remediis.

Fig. 5 and Fig 6 Franciscus Petrarcha, Von der Artzney bayder Glück, des guoten und widerwertigen, Augsburg, Heynrich Steyner, 1532, book 2, n. fol. Source: Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg, 2 Phil 57; urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb11200493-3

The illustrations created by the Petrarch Master underline the argumentative ambivalence of Petrarch’s Latin dialogues, thereby undermining any discursive victory of Ratio. The German edition proved to be enormously successful (just as Petrarch’s Latin De remediis was his internationally most read text of all his works). The great success of the German illustrated edition is definitely an effect of early-modern internationalisation. Petrarch’s text transcends the limitations of Latin humanism and opens up to a wider circle of readers who are ‘dispersed in space’. Insofar as the stoic appeals of the text were understood as maxims for action, the teutonic De remediis was able to form ‘virtual communities’ in Brint’s sense. Even more important, however, is certainly the incentive for general, culturally advanced reflection on the situation of human life in the Early Modern period, which is not limited to narrow ideological appeals, for example in the sense of a magistral preception of Ratio that would succeed in controlling the affects. The ‘imagined community’ of De remediis (and its German edition) is not a group of adepts of a stiff stoic Ratio, but all people who are able to read and willing to reflect on the human condition between reason and emotion.

There are reworkings and reprints of the illustrated German version throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The illustrations lead to an integrability of the book in the increasing tendency of moral-philosophical popularisation via the emblem books. Changes in the German title (‘Trostspiegel’ from 1572 onward) signal the compatibility of the book with the focus of a reading public interested in “bourgeois” Hausväterliteratur.

A deeper examination of the reception history of all these illustrated German editions could shed light on how the targeted audiences of the text change: the 1532 edition initially appeals, on a humanist basis, to anyone intellectually interested at all. Then, in the course of the sixteenth century, beginning with the second edition of 1539, the focus shifts to a well-read, secular and family-oriented middle class. And finally, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the illustrated editions with a reduced amount of text became interesting above all for illustrators and artists with moral-philosophical intentions (cf. the material and data in ).

In the preface to Book 1 of De remediis, Petrarch refers to the most important Latin author of the Stoic tradition of moral philosophy, Seneca (§ 10). As Seneca had done for his brother Gallio, so he, Petrarch, is providing assistance for Azzo da Correggio in the vicissitudes of life (Petrarch explicitly refers to Seneca’s book entitled De remediis fortuitorum, which has only survived in an abridged version, as the ideologically most pertinent hypotext of De remediis). Petrarch is thus not only addressing Azzo. Rather, this statement condenses the claim to provide the Early Modern period with direct contact with the philosophical commonality of antiquity; Petrarch acts as the Seneca of the post-medieval period and addresses the intellectual community of those who would like to leave the era of scholasticism (at least that is how he presents it) behind them. Beyond all intellectual circles De remediis, as a particularly “popular” text, claims to help shape the horizons of knowledge and life of a new epoch as a whole.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, this case study has discussed Petrarch’s building of multiple communities on the basis of his vernacular and Latin works using the exemplary case studies of the collection of lyric poems Rerum vulgarium fragmenta and the encyclopaedic dialogues De remediis utriusque fortunae. To do so, we addressed the difference between community (Gemeinschaft) and society (Gesellschaft, ), on the further categories of community such as “above”, “before”, “below” , and on the concept of local and dispersed friendship network . With regard to the communities created by the lyric vernacular collection, we used the notion of a ‘virtual community’ that ‘also evokes and mirrors readers’ to explore how quattrocento commentaries on the RVF reveal their characteristics of ‘social poetry’ as ‘individual and collective identity performance’ . This was demonstrated through an analysis of Patrizi’s and Acciapaccia’s commentary on sonnets 25 and 27, which revealed how the two commentators describe and at the same time seek to establish a courtly love vernacular community “below” on the one hand, and a Christian scholarly community “above” on the other.

Within the same theoretical framework, we then explored how the De remediis was conceived as addressed to elite readers who also somehow overlapped with Petrarch’s local and dispersed network of friends, first by looking at the publication strategies of the dialogue through Petrarch’s work, and then by looking at the 1532 German illustrated edition created by the otherwise anonymous Petrarch master and reproduced several times throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This reflects the various ways in which Petrarch’s expectation for the reception of his work, as expressed in the preface to Book 1 of De remediis, have been fulfilled: the desire to forge a new early modern community based on commonality with antiquity. On the basis of this shared universal European platform, described through the analysis of the exemplary case of De remediis, different networks, communities “above”, “below”, and “before” could emerge, as the study of the Neapolitan Quattrocento commentaries on the RVF has shown.