Abstract

In Digital Humanities and Computational Literary Studies, platforms like Wikidata are crucial for retrieving structured data. But how reliable is this data? This insight looks at Sappho’s Wikidata entry (Q17892) as a case study to explore issues of data accuracy, misinformation, and the impact of cultural reception. Even though Wikidata’s openness allows for extensive data accumulation, it also means fact and fiction can easily become conflated. This insight examines instances of inaccuracies in Sappho’s biography as stated in Wikidata, including the perpetuation of myths, such as her supposed leap from a cliff on Lefkada. The examples show how digital data resources like Wikidata reflect not only historical uncertainty but also centuries of reinterpretation and myth-making. This raises important questions: How should contested or unreliable data be handled? And how can verified knowledge be distinguished from the narratives that shape it? By critically engaging with Sappho’s Wikidata entry, this insight highlights the importance of data quality and critical data literacy, which serves as a timely reminder that digital data is shaped by interpretation as much as it is by information.

Wikidata: A double-edged sword

Researchers in Digital Humanities (DH) and Computational Literary Studies (CLS) often rely on data that has been captured and made freely available by others. Wikidata (Full reference in Zotero Library) is one such platform that provides structured, interconnected data. As a crowd-sourced repository, it aggregates information from Wikipedia info boxes, other Linked Data sets, and contributions from the Wikidata community itself. As of February 9, 2025, it contains more than 115 million data items.

Unlike traditional encyclopaedias or even Wikipedia, Wikidata organises information into machine-readable statements in the form of subject, predicate, and object, making it an essential data hub for the Semantic Web. In terms of the DIKW pyramid—where raw “data” is structured into “information”, processed into “knowledge”, and ultimately contributes to “wisdom” (see, for example, Full reference in Zotero Library)—Wikidata plays a key role in bridging the first two levels. Researchers and developers alike use Wikidata to query interconnected datasets spanning disciplines, geographies, and time periods (Full reference in Zotero Library; Full reference in Zotero Library).

Whether used for casual reference or the reconciliation and linking of datasets to obtain further information on certain entities, platforms like Wikidata appear to be a highly valuable resource. However, when delving deeper, the drawbacks of one of the principles of the (Semantic) Web become increasingly apparent: Anyone can say Anything about Anything (AAA) (Full reference in Zotero Library). While this principle undoubtedly encourages the production of extensive data from diverse viewpoints, it also poses questions of data quality. Given that Wikidata is such an open platform where anyone can say anything about anything, a variety of fact, fiction, and interpretation can arise. Yet, especially in fields studied by the humanities, what is considered fact is not always clear or easy to define; it is shaped by historical contexts, dominant narratives, and the ways in which knowledge is structured and transmitted. In this insight, this understanding applies particularly to biographies, which serve as an example: rather than being reconstructed from comprehensive and valid information, they are constructed through interpretation, selection, and framing. This complexity of information construction extends to digital knowledge systems like Wikidata, which, rather than offering purely factual historical records, also reflect societal assumptions, myths, and reception histories (for data quality in Wikidata, see, for instance, Full reference in Zotero Library; Full reference in Zotero Library).

To navigate these complexities, Wikidata employs a system of ranks and references to indicate the reliability and prominence of statements. Preferred, normal, and deprecated ranks help signal which claims are considered the most reliable or widely accepted, while references—using properties like “stated in” (P248) or “reference URL” (P854)—allow users to trace claims back to their provenance. Additional qualifiers, such as “sourcing circumstances” (P1480) and “nature of statement” (P5102), further contextualise data accuracy by marking statements as disputed, uncertain, or even parodic, making these nuances machine-readable without requiring users to reconstruct them from source material. Wikidata’s guidelines (as of 2024) also emphasise verifiability and discourage misinformation, advocating for the use of reputable sources and the careful handling of contested claims. In particularly sensitive or highly contested areas, editing restrictions on certain items can further help mitigate vandalism and deliberate misinformation. However, the effectiveness of these mechanisms ultimately depends on community supervision and critical engagement by users.

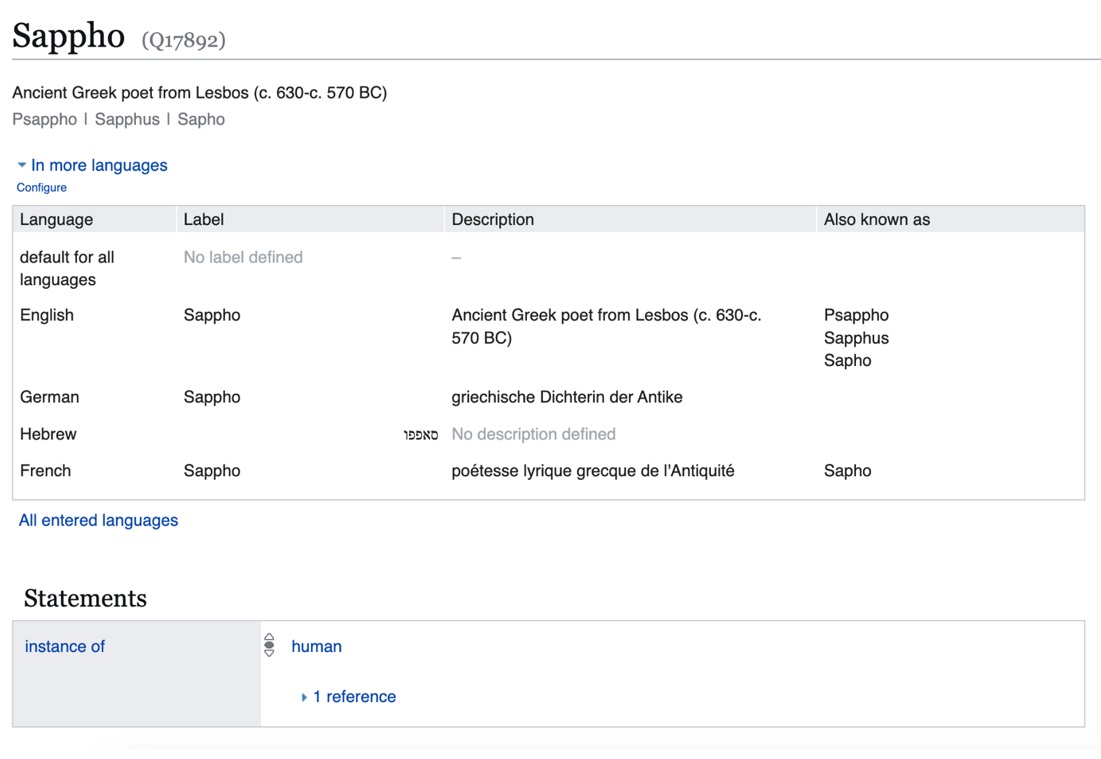

The issue of data quality in Wikidata becomes even more pronounced when examining already ambiguous topics, such as the lives of ancient figures whose biographies are steeped in mystery and speculation. To consider the example of Sappho, one of antiquity’s most celebrated poets, her lyrical works, renowned for their emotional intensity and deeply revered in queer and feminist communities, have survived only in fragments. Her life story, too, has been (re-)constructed with the aid of ancient commentary, modern analysis, and evident myth-making. There are no autobiographical documents by Sappho; only a few later records provide information about her life. Among these are the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, which have only been preserved in fragments and date from the early third or late second century BCE, the inscription chronicle known as the Marmor Parium from the third century CE, and the Byzantine lexicon Suda from the tenth century CE (for an overview of Sappho’s work and her reception history, see the selected bibliography here, for biographical sources especially Full reference in Zotero Library). In view of this, what does Wikidata “know” about Sappho? Notably, her item is semi-protected, reflecting the ongoing debates and sensitivities surrounding her persona.

This insight critically examines Sappho’s Wikidata entry (Q17892), using it as a case study to explore broader issues, especially in DH and CLS. It also reflects on the importance of questioning data provenance, interpreting erroneous datasets, and acknowledging the human factor within digital knowledge management.

What Wikidata says about Sappho

At first glance, Wikidata presents a seemingly authoritative account: Sappho was a female poet and composer, active in ancient Greece. This much is agreed upon in scholarship. However, as the subject is explored in greater detail, misinformation and contradictions quickly emerge.

Birth and death: When uncertainty and fiction become facts

As a preliminary observation, Wikidata lists approximately ten different dates of birth for Sappho, spread across three locations, as well as five proposed dates of death. Such discrepancies are, of course, understandable given the fragmentary nature of ancient sources. Sappho is not an isolated case in this regard. Concerning the place of birth, Wikidata does attempt to address these uncertainties by marking the island of Lesbos (rather than the cities Mytilene or Eresos) as the preferred value—highlighting it as the most inclusive option rather than an absolute fact. However, this ranking does not necessarily prevent misinterpretations. Users might still be influenced by authoritative-seeming references that lend credibility to individual claims, even when those claims reflect contested or ambiguous information. In this sense, the problem extends beyond Wikidata itself to external sources, such as encyclopaedias, that treat specific claims—like Sappho’s birth in Mytilene—as definitive.

Regarding the stated place of death, Wikidata mirrors one of the greatest myths surrounding Sappho. By asserting that she died in Lefkada, Wikidata perpetuates the legend of the tragic poetess, leaping from a cliff to end her life in despair over the beautiful Phaon—a story rooted not in historical fact but in Attic comedy, as Friedrich Schlegel was the first to argue (Full reference in Zotero Library). This legend persists in popular culture and, evidently, in structured datasets like Wikidata, which are assumed to contain primarily factual information. In the end, Wikidata’s statement about Sappho’s place of death exemplifies how ancient myths can become part of modern datasets, creating an amalgam of fact and fiction that demands critical scrutiny.

Residencies: Fact or fiction?

Wikidata also identifies three places where Sappho supposedly lived: ancient Syracuse, Mytilene, and Lesbos. The dataset also includes temporal information suggesting a sequence in which she first lived on Lesbos, then in Syracuse, and finally in Mytilene. At first glance, this appears plausible. Lesbos was her home island, and Mytilene is its capital. Upon closer examination, however, the idea that Sappho lived in Syracuse is connected to hypotheses about her family’s political exile. These theories, while intriguing, lack clear evidence (see, for example, Full reference in Zotero Library).

While the example of Sappho’s supposed place of death highlights the danger of misinformation originally derived from fiction, the example of her residencies underscores the risk of including statements derived from non-fictitious but still unreliable sources, conflating speculative narratives with verified information. While such conflations may seem harmless, they can mislead users into accepting unverified information as historical truth, particularly when presented in a structured and quasi-authoritative format.

Marital status: The curious case of Cercylas

Wikidata’s statements about Sappho’s marital status are equally problematic. One statement suggests that she was married, though her spouse is unknown. Another statement identifies her husband as Cercylas of Andros. This statement is flagged as deprecated, indicating that it has been widely discredited. Because Andros derives its name from the Greek ‘ἀνδρός’ (andros), the genitive of ‘ἀνήρ’ (anēr), meaning ‘man’, this name is generally regarded as a joke, roughly translating as ‘(penis)man (from the isle) of man’.

Even if plausible, there is no concrete evidence that Sappho was married at all. Yet, the presence of such claims in Wikidata demonstrates how not only erroneous but also satirical statements can appear in digital datasets, further muddying the waters of historical accuracy. The fact that the Cercylas statement was once considered credible enough to be incorporated also underscores the importance of data quality management and the risk of assuming that platforms like Wikidata automatically provide reliable information. More broadly, this highlights how misinformation, once introduced into a digital dataset, can persist even after being identified as inaccurate.

Addressing this issue requires not only marking statements as deprecated but also ensuring that outdated or misleading claims do not continue to shape interpretations. While preserving “historic” versions of data is crucial for comprehensibility and tracing a dataset’s evolution, this must go hand in hand with mechanisms that prevent deprecated statements from being mistaken for valid information. Continuous review and transparent documentation of rank changes are essential to maintaining Wikidata’s reliability as a knowledge source. However, these technical safeguards alone are not enough—users must also engage with the data critically, understanding how ranks and references influence the interpretation of statements. Without critical data literacy, even well-documented changes risk being overlooked, allowing outdated or misleading claims to persist.

The two Sapphos: A legacy divided

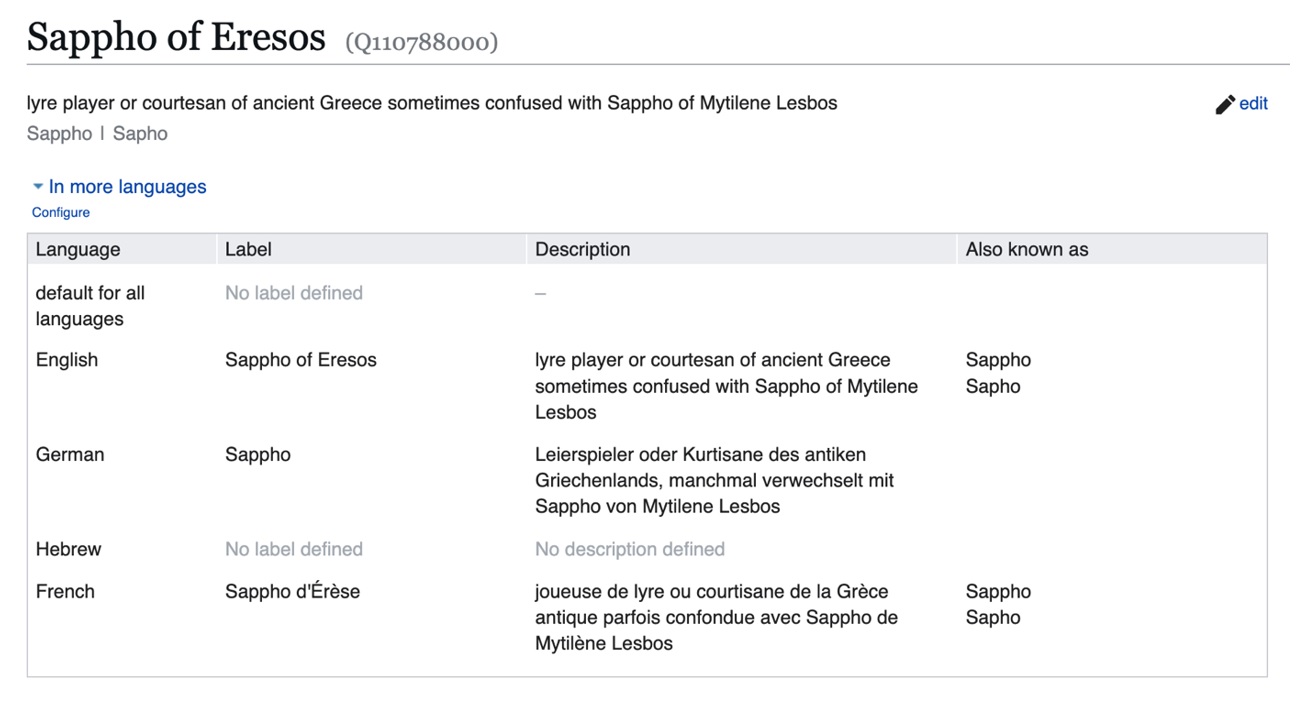

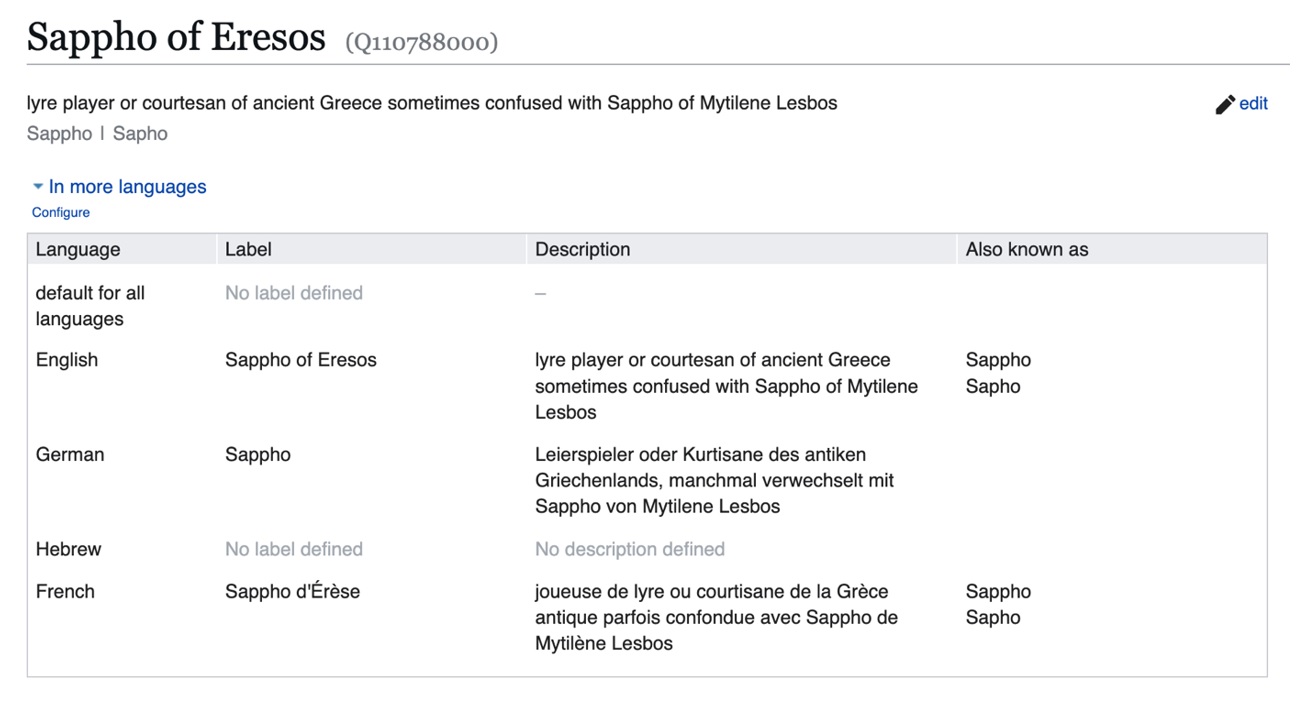

Another intriguing aspect of Sappho’s Wikidata entry is the statement advising users not to confuse “Sappho” with “Sappho of Eresos” (Q110788000). Eresos is, alongside Mytilene, the other city on Lesbos mentioned as a possible place of Sappho’s birth. Today, an organisation called “Sappho Women” holds a women’s festival there each September (Full reference in Zotero Library), and locals even claim a rock by the beach to be the very cliff from which Sappho is said to have leapt to her death (see, for example, Full reference in Zotero Library).

What is more significant, however, is that this distinction reflects an ancient attempt to reshape Sappho’s legacy (Nymphodoros FGrH 572 F6 = Full reference in Zotero Library 13.596e). The notion of two Sapphos likely arose because the poet’s original reputation—linked to hypersexuality and lesbianism—was seen as scandalous. To preserve her literary legacy without endorsing her controversial persona, ancient commentators effectively “split” her into two figures: one associated with her poetry and the other with supposed moral transgressions (Full reference in Zotero Library).

Wikidata’s inclusion of this division inadvertently echoes these ancient efforts to separate the poet’s literary importance from her perceived social impropriety. Though likely unintentional, this digital differentiation reproduces historical attempts to sanitise Sappho’s image while preserving her contributions to literature.

Wikidata as a mirror of Sappho’s reception history

The distinction between the two Sapphos, along with the misinformation and uncertainties reproduced in Sappho’s Wikidata item, ultimately demonstrates how Wikidata reflects, to a great extent, Sappho’s reception history and her biographical representations rather than verified information. From antiquity to the present, Sappho has been imagined and reimagined in countless ways—both in scholarship and artistic interpretation—each one revealing more about the societies interpreting her than about the poet herself. Wikidata, in taking up many of the uncertainties and speculations present in Sappho’s reception history, functions as a partial mirror of this ongoing process of reinterpretation, appropriation, and framing. The result is a dataset that reveals as much about how Sappho appears in the imaginaries of the data keepers.

This does not imply, however, that the presence of contested or even erroneous claims in Wikidata is inherently a flaw. The heterogeneity of Wikidata’s data also provides a valuable resource, especially from a humanities perspective. Instead of striving for a singular, definitive account of Sappho, Wikidata’s structure allows for the coexistence of multiple perspectives, making visible the historical and cultural processes that have shaped her legacy. In this sense, rather than simply removing incorrect or disputed claims, the key challenge is ensuring that their contested nature is made explicit and that users are equipped to navigate these complexities.

Wikidata, then, does not serve as a straightforward factual record of Sappho’s life. Rather, it encapsulates the tangled web of historical interpretations, cultural shifts, and fictional embellishments that have shaped her legacy. This also points to a broader dynamic: the datafication of cultural memory. When myth and speculation are transformed into structured data, they can appear as factual knowledge. Examining these layers of data offers insight not just into Sappho’s life—still largely elusive—but also into the ways in which she has been remembered in different historical, cultural, and political contexts.

Therefore, Wikidata is more than a static repository; it is a living archive of human interpretation, continuously evolving as new data and perspectives emerge, reflecting how data—and by extension, knowledge—is shaped by interpretations and the narratives constructed from them. This fluidity presents both challenges and opportunities: while it requires careful navigation, it also invites critical engagement with the ways in which knowledge is structured, contextualised, and framed. And this very process—the organisation, debate, and reshaping of information over time—makes Wikidata an interesting case study for the humanities.

From data to information: The role of interpretation

In the end, the inconsistencies and misinformation in Sappho’s Wikidata entry illustrate how data alone does not constitute information or even knowledge. Data must be analysed, interpreted, and contextualised to yield meaningful insights (Çakir 2024; see also Soethaert 2024). From a humanities perspective, Dîlan Canan Çakir notes that the term “data” is as nebulous as the term “literature” (ibid.). Both are open to interpretation and shaped by the contexts in which they are used. For this reason, Johanna Drucker (Full reference in Zotero Library) proposed the term “capta” to emphasise the constructed nature of data, and Matthew Lavin (Full reference in Zotero Library) suggested “situated data” to account for its contextual dependencies. In the case of Sappho, the data presented in Wikidata is, as has been shown, entangled in centuries of myth-making and scholarly debate.

This raises important questions for researchers: How should contested data be handled? To what extent are platforms like Wikidata reliable in providing accurate information? And how can historical facts be distinguished from the narratives that have accrued around them over time?

In DH, the need for critical data literacy is great, especially when working with historical data or figures. This involves not only developing the technical skills necessary to create and use datasets but also honing the analytical skills required to investigate the assumptions underlying them. Sappho’s Wikidata entry underscores why critical data literacy is essential: it reveals how structured data serves as a foundation for information, yet also embeds uncertainties, misinformation, and myths that challenge the process of knowledge formation. While mechanisms for ranking statements and attributing sources exist, their effectiveness ultimately depends on how they are applied and interpreted. Ensuring that disputed or uncertain claims are properly contextualised—and that users engage critically with the data—remains an ongoing challenge.

Rather than assuming that structured data guarantees objectivity, Wikidata should be recognised as a dynamic, evolving repository that requires continuous scrutiny and refinement. In much the same way that a printed text would be critiqued and challenged, so too the digital data that informs an understanding of the world must be critically analysed and evaluated. However, unlike a printed text, which remains static once published, Wikidata is dynamic and evolving, continuously shaped by new contributions and revisions. This also presents an opportunity: Wikidata allows for the continuous correction, refinement, and expansion of information. Ultimately, its interactivity makes critical engagement not only necessary but also more accessible, enabling users to participate actively in refining and contextualising the data rather than merely consuming it.

In an era where digital knowledge systems are becoming increasingly central to DH and CLS, researchers in these fields must develop the skills and methodologies necessary to engage with this data critically and thoughtfully. The key is to ensure that myth is not conflated with fact—even if DH projects that make use of Wikidata tend to prioritise data coverage over data accuracy (Full reference in Zotero Library). Structured datasets, despite their authoritative appearance, are still subject to human interpretation, historical bias, and misinformation. Engaging with these sources requires a responsible balance of technological proficiency and scholarly scepticism, ensuring that both the possibilities and the pitfalls of digital knowledge systems remain clear.