Abstract

E-quotes are quotes created for the purpose of being posted on digital platforms. The aim of this insight is to investigate how literary e-quotes posted on Facebook pages demonstrate a new practice of valuation that contradicts traditional practices related to the “offline world”. Focussing on two Facebook pages, whose content is inspired by excerpts taken from multiple literary works, this research explores how the concept of value is re-worked by generating new practices or modes that do not only emphasise the role of digitality, but also raise the question of agency and the role of new actors. For the purpose of this research, the insight is divided into two parts: the first demonstrates how literary e-quotes represent a transformation of traditional print literature into digitised content; in other words, how the value of literary works is re-worked through “datafication”, which turns these works into data so that they can be easily accessed and circulated. The second part analyses how valuation, as a practice, is communicated among members of digital communities. In this regard, the notion of value as a quantifiable form is tracked through the lens of the different responses that posted e-quotes generate. The analysis of different patterns of response demonstrates how digital communities become an active agent that take part in identifying the value of the digital content produced.

Introduction

Valuation defined

In an attempt to define valuation, John Dewey in his Theory of Valuation , demonstrates the different meanings that the word expresses. He emphasises that the etymology of the word leads back to the word “value” which is employed to indicate: a) ‘prizing’ in the sense of ‘holding precious, dear’, and b) ‘appraising’ in the sense of ‘putting value upon, assigning value to’. Valuation as prizing, he states, correlates with the belief that valuation is an activity that is based strongly on ‘personal reference’ or is ‘emotional’ . In this regard, valuation is considered an act of ‘rating’ that leads to values that represent ‘emotional epithets or mere ejaculations’ . On the other hand, valuation as appraisal is linked to ‘relational property’ . Valuation, in this sense, has been viewed as an ‘interpersonal activity’ that aims at evoking ‘certain responses from others’ . If the first definition identifies valuation as a personal act that involves ‘desire’ , the second definition pinpoints the fact that valuation could also represent activities that are based on the interaction between different individuals. In this regard, valuation is considered a ‘social’ activity by which groups or actors, through ‘organised channels’, are able to ‘obtain and make secure conditions that will produce specified consequences’ and/or standardised values.

Similar to Dewey, Claes-Fredrik Helgesson and Fabian Muniesa define valuation as the values resulting from an individual’s emotions and desires, on one hand, and as a social practice that entails the engagement and interaction between several actors, on the other . Despite resembling Dewey’s view, they both differ in focussing more on the demonstration of valuation as social practice by emphasising the different features that characterise it. The first feature of valuation is based on the idea that value is the ‘outcome of a shared belief: value exists because people think it does’ . According to Helgesson and Muniesa, value is the result of a ‘process of social work’ generated by a wide ‘range of social activities’ with the aim of ‘making things valuable’ . The second feature is that valuation is a process that ‘takes many forms’ . For instance, some activities of valuation are based on the establishment ‘of a monetary price’, while others are ‘non-monetary’ because they assess the quality of an object . The third feature is that value is ‘institutionalised’ . Since value—as a social practice— is ‘socially constructed’ , actors have to act through certain ‘channels’ to guarantee that they share and produce same values. This connotes that valuation is an act that undergoes continuous processes of ‘objectification’ (Helgesson and Muniesa 2013: 7). The fourth and last feature relates to the ‘re-ordering effects’ of valuation . It should be asserted that different practices of valuation have the power to change the order and/or re-order the value of an object.

Valuation digitalised, valuation democratised

According to Francis Lee et al., digitising valuation has two associated concepts: the first is “datafication” and the second is “quantification” . Datafication means ‘rendering things in the world as data which can be saved, edited and circulated’ . Quantification, on the other hand, stands for the idea of changing ‘things into numbers’ . Datafication and quantification are, then, considered the two pillars that formulate the ‘infrastructures’ of digitised forms of valuation . Despite the fact that forms of valuation do not ‘emerge out of nowhere and do not appear in isolation’—an idea that signifies how valuation is an act of evaluation that is based on ‘judgements, norms, and habits’—digitisation greatly contributes to re-forming ‘spaces’ by generating ‘new modes of intervention’ that give actors more agency and power . These new modes of intervention raise the question of democratising valuation by building new channels that allow public actors to formulate and generate new modes of intervention. Generating new channels enables ‘new possibilities for discovery and intervention’ and makes data more accessible.

Aim

The aim of this insight is to investigate how valuation has been viewed through the lens of social media, which not only helps to move valuation from the restrictions of institutionalisation to the new realms of democratisation, but also emphasises how digitality generates new forms of (valuation) practices.

Case study: literary e-quotes

This research investigates literary e-quotes. Valuation is correlated to selected samples of e-quotes to explore how the notion of value is formulated on two levels: the first examines value in relation to the production of digital content that is primarily published as it is in print (e.g. printed novels). E-quotes from literary works assert the idea that value, as a process, is constructed by digital communities that have the freedom to pick and choose specific segments and post them to their followers. E-quotes, insofar as they demonstrate value, are a good instance of datafication. The second focusses on valuation as a social practice, which is evidenced in the responses of users who react differently to the e-quotes posted. Democratising valuation is achieved through the responses that users send. The responses to selected samples are good instances of datafication and quantification on the level of the e-quotes readers.

The sample webpages selected for this research are: Arabic Facebook page اقتباسات من روائع الأدب (Quotations from Literary Masterpieces) and English Facebook page Literature is My Utopia. The following section is divided into two parts: the first shows instances from the two webpages to show how value is re-produced through posted literary e-quotes, whilst the second emphasises how these e-quotes are consumed by the followers of the two pages.

The re-production of value

To understand how value is democratised, it is essential to demonstrate how value is created and re-worked. The examples discussed under ‘the re-production of value’ emphasise how literary e-quotes contribute to a revival of literary texts that were previously circulated through and only read in print form (i.e. books). In other words, e-quotes posted on Facebook pages represent the new channel that grants followers/readers free access to literature. Instances in this section show different ways value is produced through the multiple options that social media platforms provide for generating content.

Example 1

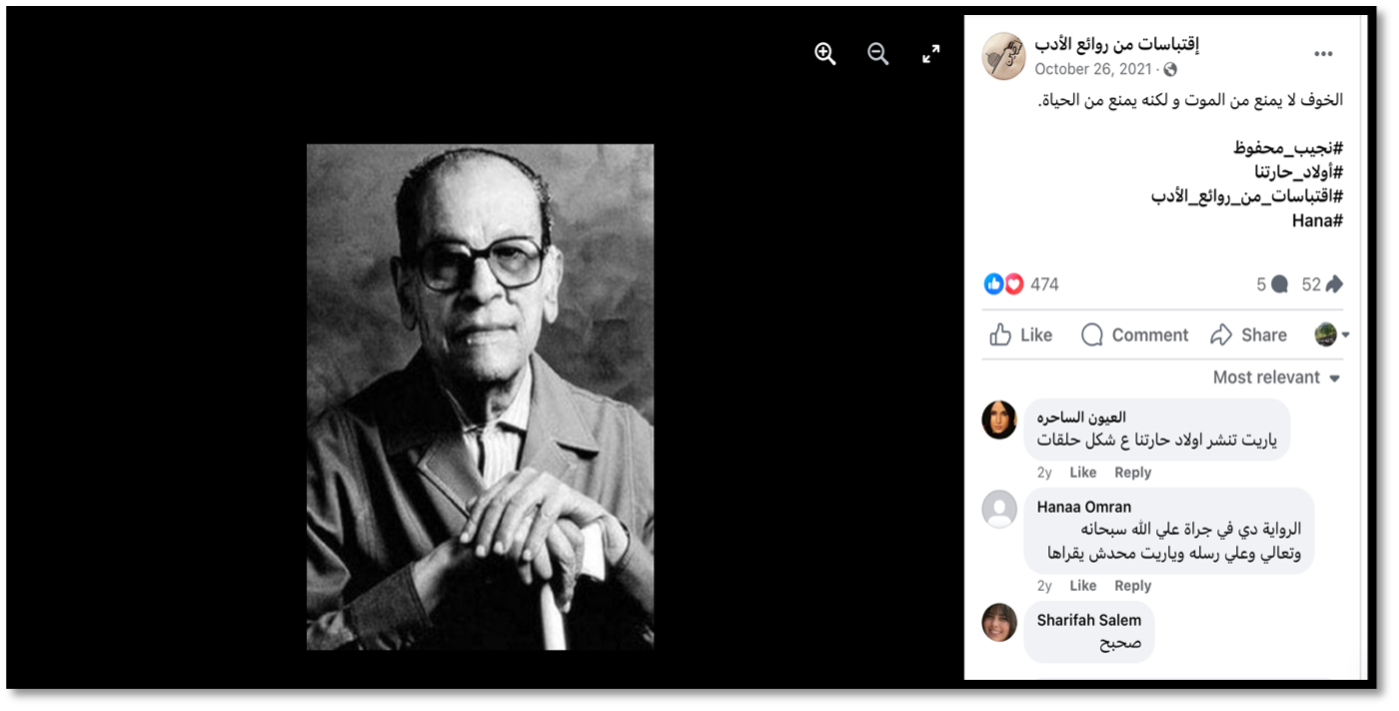

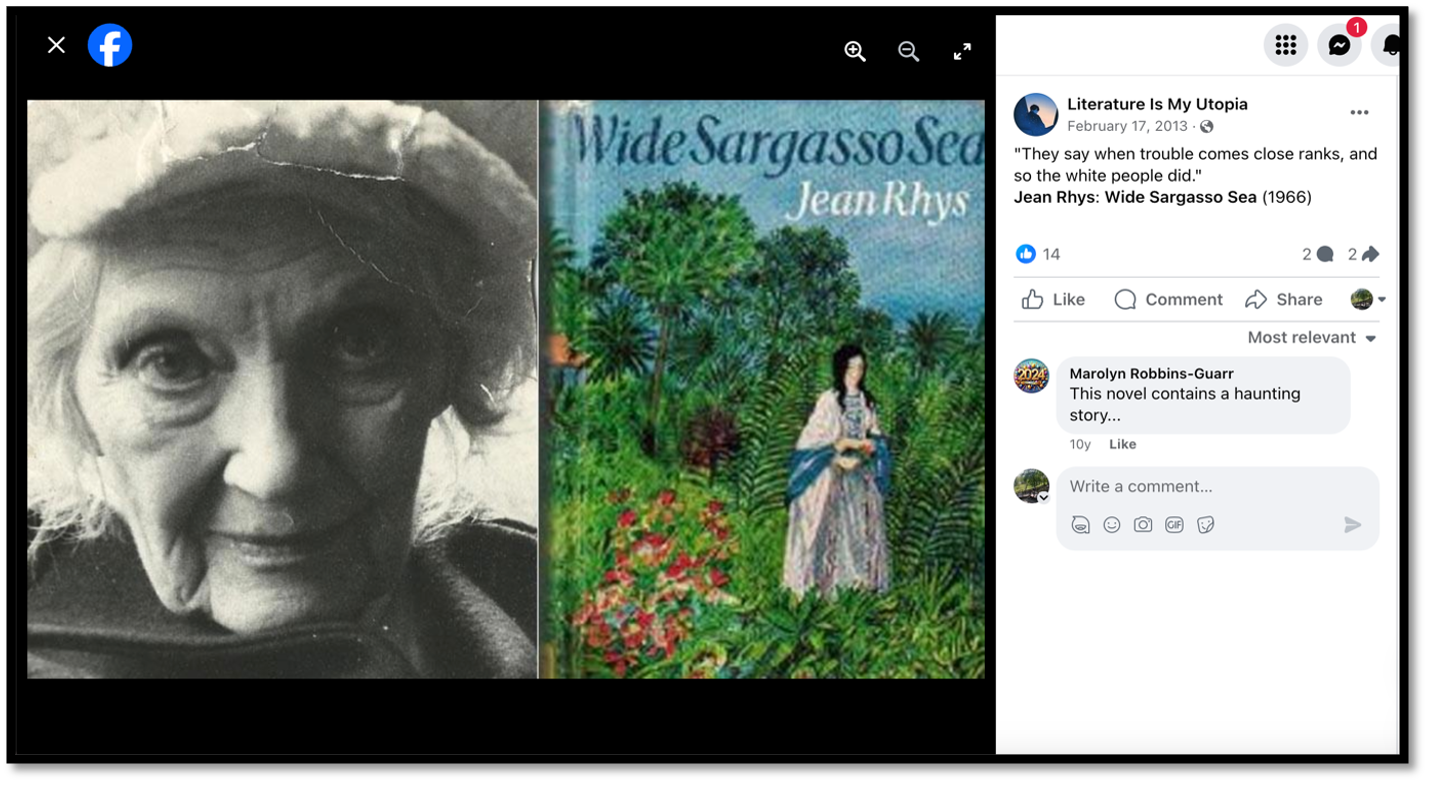

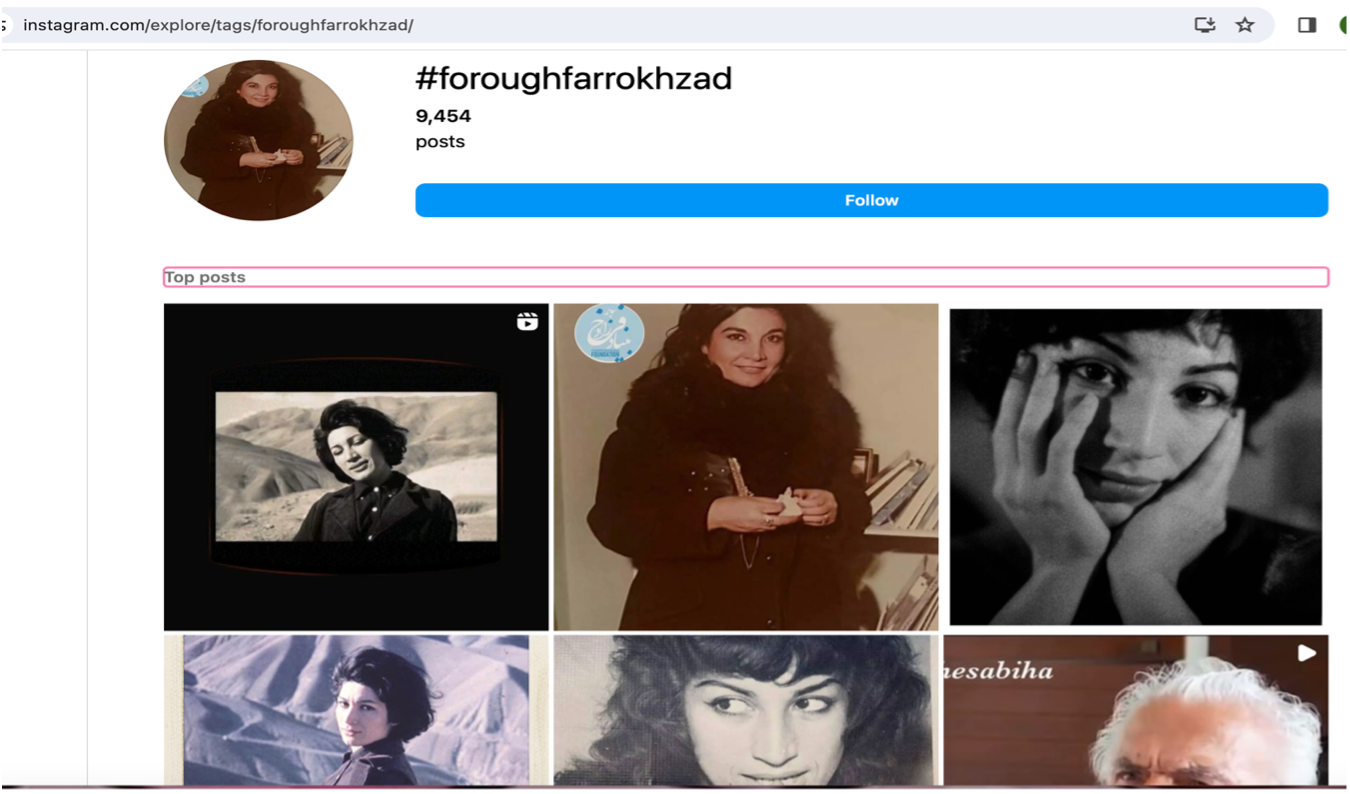

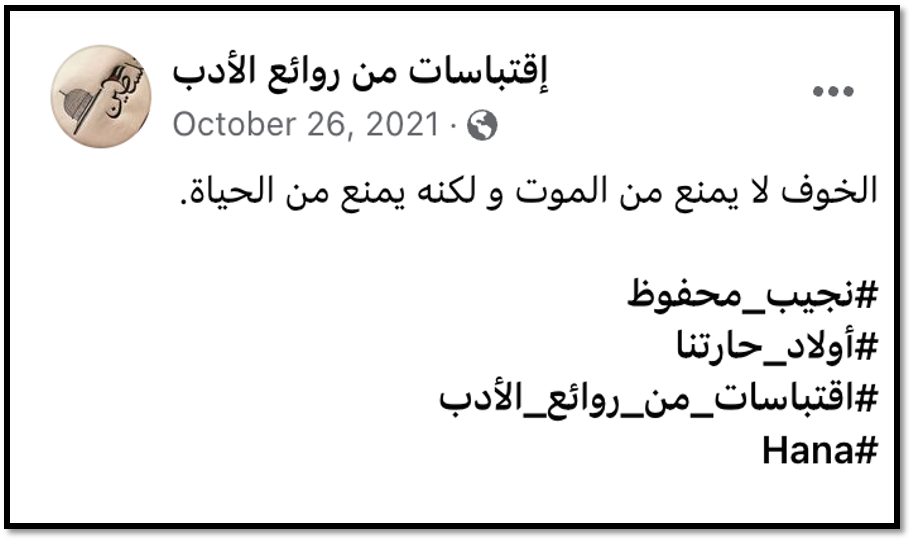

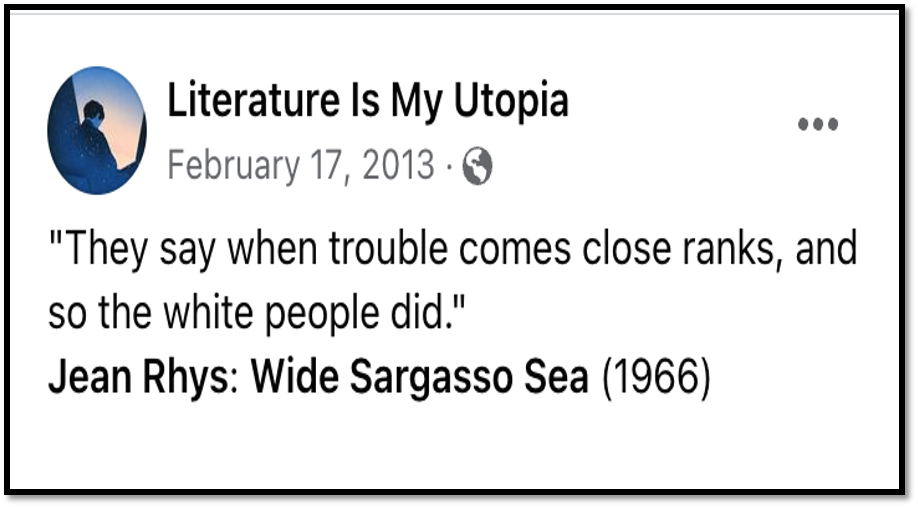

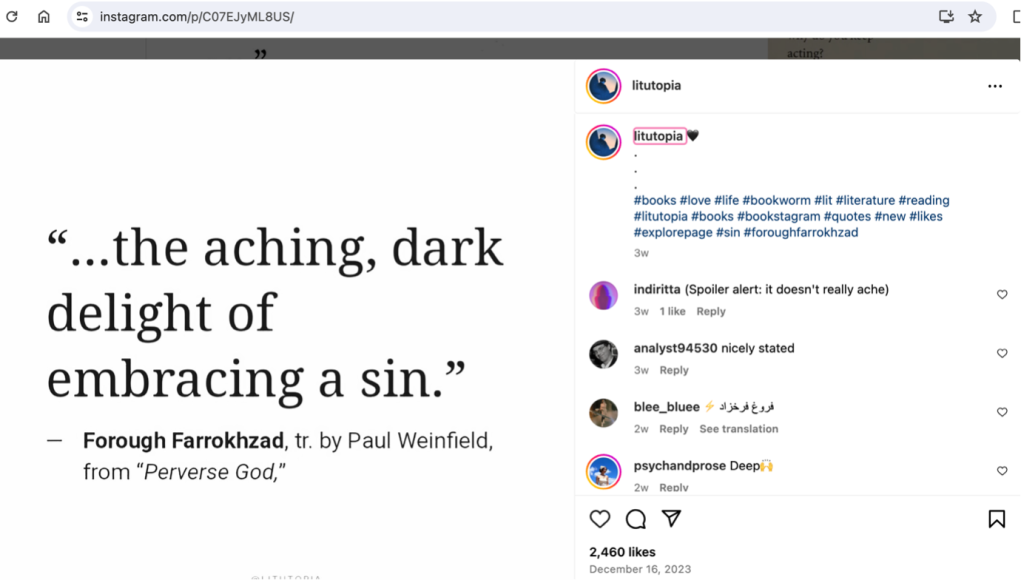

Fig 1 shows an e-quote from the 1959 Egyptian novel Awlad Hartena (Children of the Alley) by Nobel Prize-winning novelist and writer Naguib Mahfouz. The text quoted in the image reads: ‘Fear does not prevent death. It prevents life’. Fig 2 shows an e-quote from the 1966 novel Wide Sargasso Sea by British novelist Jean Rhys. By linking the two e-quotes to the notion of valuation, this emphasises two dimensions: first, the transformational power of valuation, which is evident in the new value that the two texts acquire and, second, the correlation between valuation, as a social practice, and datafication. In view of the first, one of the remarkable changes the two texts undergo relates to the new channel where they are published. The two texts no longer exist as part of a novel’s print page, where they were originally produced, but they gain greater emphasis by being posted independently on the two Facebook pages. In the two instances, textual and graphic-visual elements are used to create the new format of the e-quote (as a Facebook post) and to assert their authorship. For textual elements, Fig 2 shows the text within quotation marks, followed by the novelist’s name and the novel’s title, both in bold. Also, the year when the work was published is present. The bibliographical information that follows the e-quote is treated as keywords that link it to other e-quotes posted on other Facebook pages, having all or some similar keywords. In Fig 1, “keywording” is done in a more effective manner through the use of hashtags.1A hashtag is: ‘a word or phrase preceded by a hash sign (#), used on social media websites and applications […] to identify messages on a specific topic (ODE)’ .

According to Aleksandra Laucuka, the ‘communicative functions’ of hashtags are evident in their role in ‘marking topics’ and ‘aggregation’ . Tagging a text means ascribing it some markers that allow public users or readers from other pages to reach it easily. In addition, it allows readers access to other texts that carry the same tagged keywords. In this regard, the use of hashtags not only extends the existence of e-quotes beyond the borders of the page, but it also encourages wider dissemination of the text by aggregating it to other posts that have similar keywords. The e-quote in Fig 1 has four major hashtags: the first carries Mahfouz’s name as a direct marker to the work’s writer. The second indicates the title of the novel as another direct marker. The third shows the name of the Facebook page, which is considered another marker that guides readers from other pages to the location of the e-quote. The fourth is the name Hana, which refers to the person who creates and posts the e-quote.

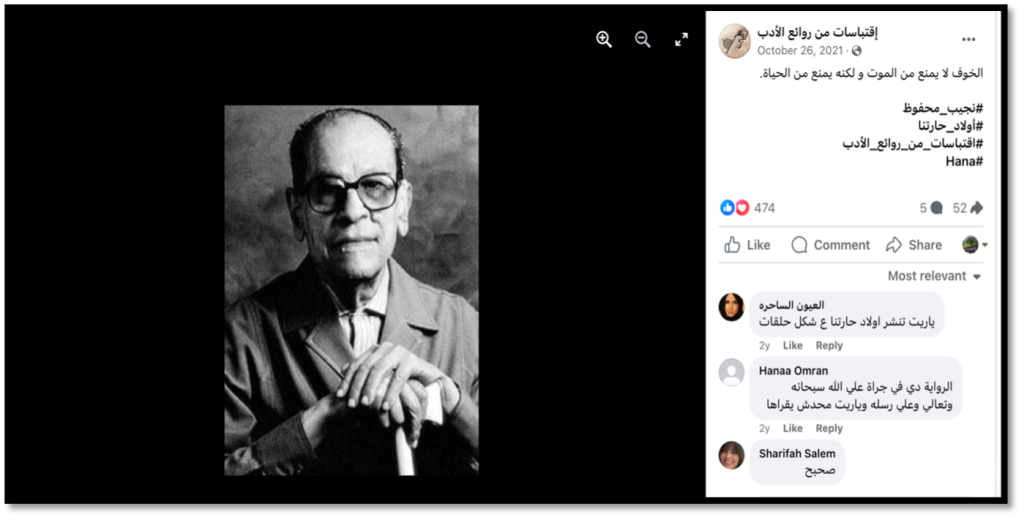

Moving to graphic-visual elements, which assert the transformational effect of valuation, the two e-quotes are accompanied with photos of the two novelists. In Fig 3, the E-quote stands alongside Mahfouz’s photo on the left side of the page:

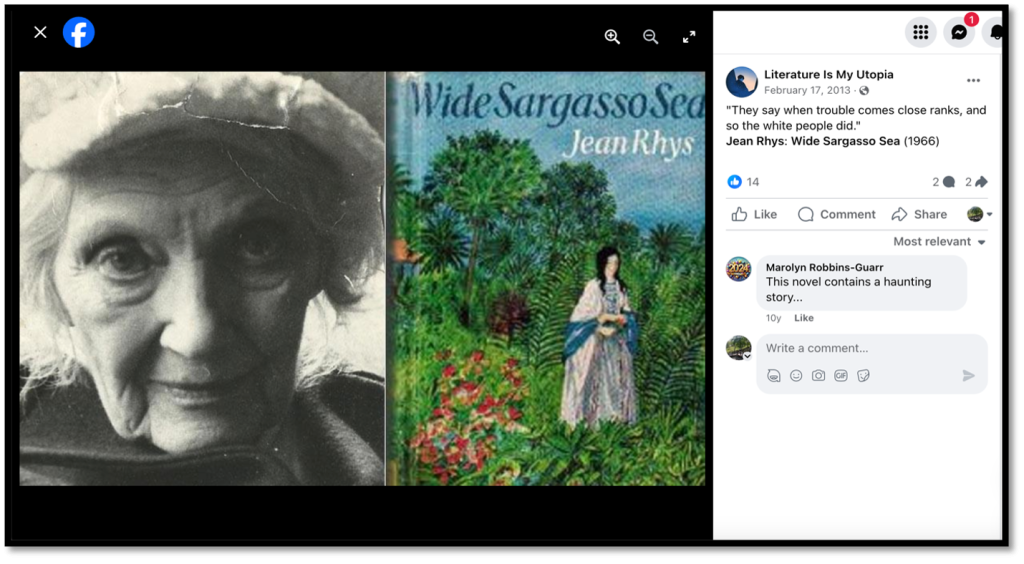

In Fig 4, the image, on the left-hand side shows Rhys’s photo and the cover of the novel:

The transformational effect of this enactment of valuation—by adding images to e-quotes—demarcates the limited options of print pages when compared with the multimodal options that digital pages of social media platforms provide. In the two examples provided, content creators rely on multimodal options while posting the e-quotes. The link that has been made visual—by adding the photos of the two novelists—remind the readers of the original authors. The photos also provide the two texts with a graphic identity that was asserted textually by the metadata referenced with each photo.

Datafication, the second dimension related to valuation, emphasises in the two examples provided: a) the effective role of digital communities in re-working and reviving literary texts. Posting specific parts from literary works changes traditional reading behaviour. Instead of reading a complete work, readers focus on e-quotes representing part(s) of the work. The value of reading, as a behaviour, shifts with the change of medium; b) the use of referential data and hashtags transforms literary texts from steady, fixed entities found in books into flexible, easily shareable content that becomes part of the ongoing flux of data on the web; and c) linking texts to other texts and/or digital content produced on other pages through hashtags highlights how datafication manifests valuation as a social practice that is no longer monopolised by mainstream institutions but is practised by actors who can create new spaces where selected data circulates freely.

Example 2

Example 2 shows another form that presents a different view of value which, here, correlates to what Katherine Hayles calls ‘electronic textuality’ . In her ‘Translating Media: Why We Should Rethink Textuality’, she emphasises that the internet has, undoubtedly, led to a contemporary re-conceptualisation of textuality. Electronic textuality, she believes, has many features that formulate a new view of textuality and its value: first, it ‘transported’ the print text not only ‘into a new time but a new medium’ . The transfer of the text to the electronic medium not only guarantees the revival of that text, but it also indicates a change in the ‘navigational apparatus’ for reading it. Second, the transformation of a print text into an electronic text is, in itself, a ‘form of translation’ , which is evident in how electronic texts allow for a re-interpretation of the text that ‘presents us with an unparalleled opportunity to re-formulate fundamental ideas about texts and, in the process, to see print as well as electronic texts with fresh eyes’ . Third, visuality is a new value that is highly connected with electronic textuality. Access to print texts, especially old ones, requires ‘access to rare book rooms, a great deal of page turning, and the constant shifting of physical artifacts’ . The massive processes of transforming print texts into electronic texts entails generating visual versions that simulate earlier versions of that text. Adding to that, these electronic versions are easy-to-access anywhere and anytime.

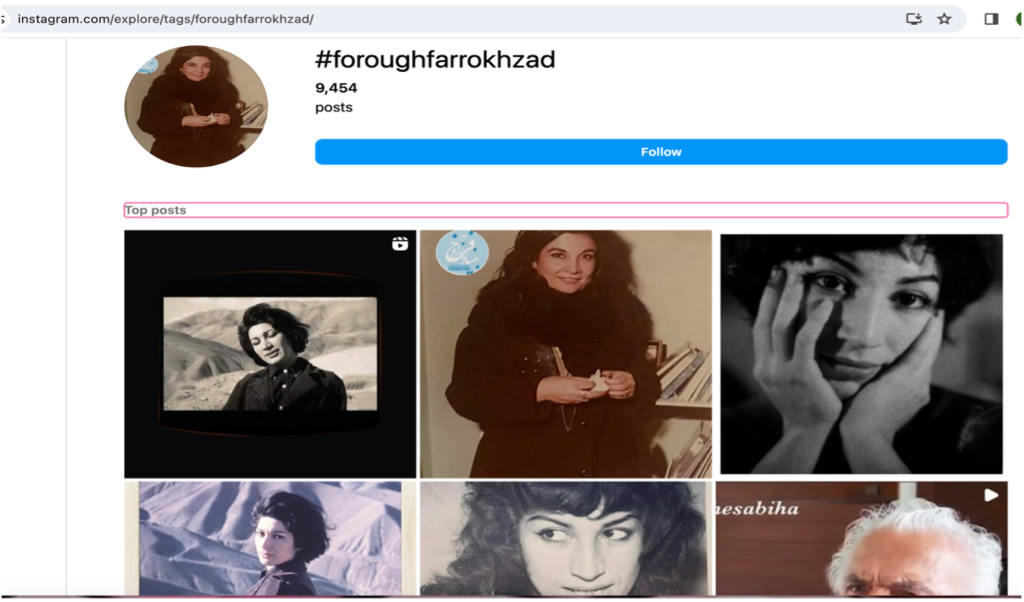

Figs 5 and 6 show instances of e-quotes generated from two translated works: the first is an excerpt from the British novelist Agatha Christie’s The Murder at the Vicarage published in 1930, whilst the second is a line taken from the Persian poem ‘Perverse God’ by Forough Farrokhzad, translated into English by Paul Weinfield in 2015. Linking e-quotes in Figs 5 and 6 to the features of electronic texts emphasises the following features: the first feature of electronic textuality draws attention to the effect of the new medium, by which texts transform from their print nature into the electronic one. A major value of a text as an entity lies in its structure, which is based on a ‘hierarchal set of content objects such as chapters, sections, subsections, paragraphs, and sentences’ . In the case of e-quotes, the hierarchy of the text is no longer essential and it is deconstructed, allowing for a new ‘independent aesthetic production’ to begin . Figs 5 and 6 reflect excerpts, and not full parts of literary texts. Deconstructing a text’s hierarchy leads to: a) a new textual form being generated that will be viewed and valued differently by readers of the two pages, and b) the production of new forms (i.e. e-quotes), which demonstrates the power that valuation, as practice, has to change and to democratise traditional forms.

The second feature of electronic textuality brings translation, as a process, into question. César Domínguez states that translation functions as a necessary ‘tool’ of ‘mediation for literary works’ with the purpose of reaching ‘wide audiences who cannot read in the source language’ . The text in the two e-quotes has undergone two levels of translation: the first is evident in how the text opens opportunities for re-interpretations and re-readings of its ideas. The text in its electronic format encourages readers to see it ‘with fresh eyes’. Datafication, on this level, relates to the transformation of a text into a digital format that ‘is generated through multiple layers of code processed by an intelligent machine before a human reader’.

Literal translation emphasises that the value of producing e-quotes that extract their content from a translated work is that it transfers the literary text from one culture (source language) to another (target audience). The e-quote from Christie’s text (Fig 5) reads: ‘The young people think the old people are fools; but the old people know the young people are fools’. Presenting this line as an e-quote in Arabic makes it available for readers who might not read the text in its original language. Similar to Fig 5, the translation of a Persian poem opens new access points that broaden its readership. Datafication is evident through translation and its ongoing role in re-presenting the text in different languages.

To return to the link between features of e-quotes and electronic textuality, the third feature is visuality, as a value. The transformation of traditional text into an electronic text indicates the new visual effects that become essential components of the electronic text: ‘screen design, graphics, multiple layers, color, [and] animation’ are easily added to the text . Like Figs 3 and 4, graphic-visual effects are evident in the two instances discussed. In Fig 7, the screen’s layout shows the e-quote standing independently on the right-hand side of the page. On the left, a monochrome photo of Christie is present:

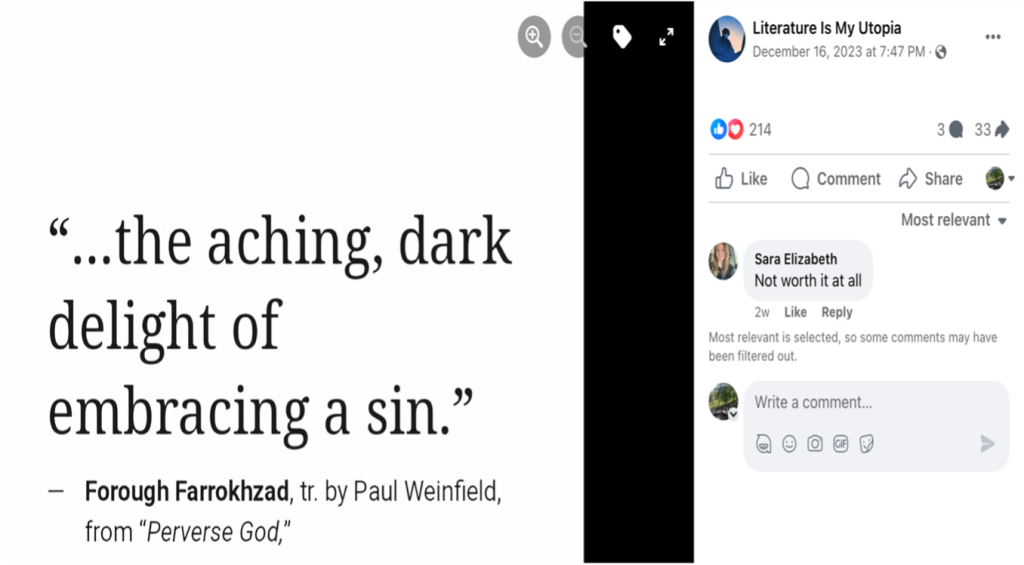

In Fig 8, the text dominates the left-hand side. Visual effects, in this sense, are evident in the different font sizes selected for the texts, the type, and the colour of the font. The line appears in a large black font; while the poet’s name is in bold, the translator’s name and the poem’s title are all in a smaller black font:

The fourth and last aspect is dynamicity, which becomes a new value related to electronic texts. According to Hayles, one of the gains of the web is that it creates ‘communication pathways’ that put electronic texts in a ‘cycle in dynamic interaction with one another’ . This cycle generates a “cluster” of related texts that are strongly interconnected . In Fig 9, like Fig 3, hashtags at the end of the e-quote are markers that connect the text to other texts carrying the same information. For example, the first hashtag after the text is the name Agatha Christie underscored. When the tagged name is clicked it leads to 19K posts, from different Facebook pages, that have the same name:

In Fig 10, the dynamic interaction between the e-quote and similar texts is achieved through different means, as it occurs beyond the walls of Facebook. The page has other accounts on Instagram and Twitter. On the page’s Instagram feed, the same e-quote exists with the same layout:

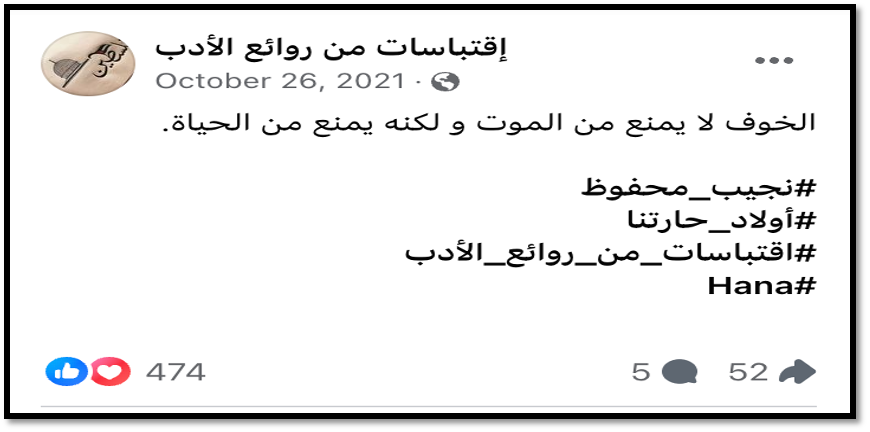

Despite the fact that there are no hashtags on the Facebook’s e-quote, various hashtags are used on the Instagram page. These hashtags create new cycles that connect the text to new content. For instance, by clicking on the last hashtag signifying the poet’s name, the reader is led to another page that shows photos of the poet:

The circulation of value

The previous section demonstrated how e-quotes manifest the production of value, which is evident when a discourse, based on excerpts taken from literary works, is created. In this section, valuation as a social practice is explored through the lens of the different patterns of response that turn readers’ reactions into data that can be measured. An analysis of readers’ responses to e-quotes draws attention to the question of agency and the extent to which readers become actors whose responses—to the e-quotes posted—democratise value; users and readers play an active role in shaping this value.

With the ongoing waves of datafication, by which aspects of life are turned into data that can be easily downloaded and accessed, the possibility of “datafying” human emotions and reactions has become an issue worth questioning. According to Maria Arnelid, Ericka Johnson, and Katherine Harrison, digital technologies make emotions ‘tangible, measurable, and accurately reproducible’ . Similarly, William Davies emphasises how digitality leads to a shift in the view of emotions: from being a “subjective” and “immediate” reaction to a specific situation or experience, to an “objective” and “calculable” form that can be tracked and measured . This shift of emotions to a ‘measurable and quantifiable’ form signifies a change in its value from being a spontaneous reaction that takes place ‘in the moment’ (i.e. ‘physiological state’) to a ‘social and cultural practice’.

Examining Facebook, there are two major response options available for users: a) Facebook reactions and b) comments. Early stages of Facebook witnessed limited reactions, which allowed users to click the “thumb-up” as a sign that they liked something, or a “thumb-down” to indicate that they disliked it. At this stage, the process of valuation was limited and users were restricted to one of the two response options available. Attempts to broaden the reaction options for users is ongoing, and its most recent development provides users with seven emojis to express their reaction: “thumb-up” for liking, “heart” for love, “heart-hugging-face” for caring, “haha-face” for laughing, “wow-face” for surprise, “animated-teared-face” for sorrow, and a “pouting-face” for anger. Increasing the number of emojis not only indicates that more emotions are quantified and become measurable, but also signifies a progress in the evaluation process as it becomes more precise and indicative of what users feel and how they value the content presented to them.

Moving to comments, when using the comment options, users become more expressive as they have the freedom to formulate textual messages that explain or show their reaction. Example 3 shows how readers respond to an e-quote posted using different emojis, as shown in Fig 12, whilst Example 4 presents instances from comments posted in response to the e-quote shown above in Fig 2:

Example 3

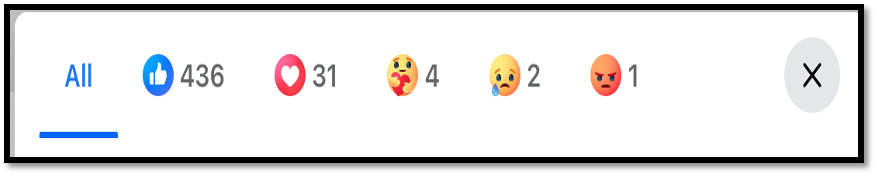

The e-quote shown in Fig 12 received a total of 474 emojis from the readers of the page. As the screenshot below shows, Mahfouz’s e-quote received 436 “thumbs up”, indicating the number of likes, thirty-one hearts, which represent a higher level of appreciation for the post, four “face-carrying-a-heart”, indicating an increasing level of support for the e-quote, two “crying faces” that reflect sad feelings aroused in reaction to the e-quote, and a “pouting-face”, which, when linked to the context of the e-quote, might indicate regret or disagreement:

Responses to Mahfouz’s e-quote. Quotations from Literary Masterpieces. April 9, 2023.

The detailed record of the reactions posted in response to the e-quote highlights the following points: first, the numbers are quantifiable indicators of the contributions and reactions posted in response to the quote. Second, providing the total number of readers’ reactions reflects what Arnelid, Johnson, and Harrison emphasise about the role of social media platforms and their ability to transform emotions from a physiological, spontaneous state to a form that can be measured, documented, and made tangible . The physical appearance of reactions through emojis shows how the element of tangibility is realised. Third, the use of reactions on Facebook demonstrates the nature of data and how it is valued in various ways using quantification techniques like emojis. Fourth, reacting to the e-quote using emojis is an example of how valuation is a social practice that is lived and experienced by the webpage’s digital community. In other words, the act of posting emojis to is a communal, shared behaviour that members of the page follow to express what they feel and also evaluate the e-quote. Fifth, the various emojis responding to the e-quote is evidence that valuation, as a process, has become a democratised act that is available to a larger number of readers, who become engaged actors who freely express their emotions as reactions towards the content posted.

Example 4

The screenshot above shows two comments posted to the e-quote in Fig 14. The content of the two comments varies, since the first comment includes a laughing reaction using the (=) symbol followed by the letter (D). The page’s follower tags a friend’s name before the laugh sign. In the second comment, the page’s reader sends a textual message that expresses her opinion of the story, which she finds ‘haunting’. The two comments emphasise: first, the free space that readers have to express their views in more detail in a textual format (if compared to emojis) to the comment they send. Second, tagging a friend while commenting is one example of how digital content circulates among social media users. The friend might not be one of the followers of the page; however, tagging her indicates that the e-quote reaches her. Third, the comment option is, besides a reaction, an instance that shows how users become actors who have the freedom to generate responses that reach beyond the limited options for reacting offered by the platform. Fourth, comments extend e-quotes, in the sense that new texts are generated in the form of comments. Describing the novel as ‘haunting’ reflects a personal view of the text and encourages other readers to respond to this view, thus creating a thread of comments that add new meanings or readings to the original content. Fifth, comments are a good example of how valuation, as a practice, is enacted through a different strategy that allows readers an opportunity to express what they see in greater detail.

Conclusion

Despite the idea that value, in its essence, is the outcome of a subjective impression that is based on personal desires, it is essential to confirm that it could not stand in its final and full shape until it becomes a collective act that is practised by members of the community. Digital media has opened the doors wide for the birth and presence of new modes of connectivity and intervention that, despite being experienced and practised communally, demonstrate the active role of individual agents who find new spaces for generating and re-producing new forms of valuation. E-quotes are considered a manifestation of a recently generated, digitised form of value, which exposes readers to alternative experiences when they are exposed to digital content. Using Facebook as a case-study, this insight has aimed to explore how this social media platform serves as a channel for generating content that is widely circulated and responded to by readers. The notion of “value” or “valuation” is investigated through the two major precepts of datafication and quantification. Datafication is evident through the ability of e-quotes to revive excerpts from literary works, which, when circulated outside of their print form, within the more open medium of digitisation, signify the wider circulation of its content. Quantification sheds light on the role of readers as active agents who add new meanings to the concept of value through the various methods they use to respond to the e-quotes posted. Future research can take this insight as an initial step for an exploration of more forms of valuation that are present on different social media platforms.