Abstract

This insight provides an analysis of the representation of farm animals on TikTok. It outlines the main categories through which users come into contact with animals on the social media platform, and the cultural meanings they carry. Between narratives of empathy and alienation, social networks are involved in negotiating our contradictory relationship with other animals.

Introduction

The ways in which we perceive and assign value to farm animals’ lives are, as is the case for most nonhuman beings, multiple and contradictory. Farm animals are, first of all, food. The primary function of the billions of farm animals reared each year around the world is to be processed into food products.1An estimated 92.2 billion land animals are kept and slaughtered annually in the global food system, according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation. See FAOSTAT. As a consequence of our food habits, farm animals are merchandised. Their lives have a (very low) economic value. As beloved protagonists of a large part of children’s literature and culture, they have also acquired an affective value. As part of a bucolic imagination of the countryside constantly activated in marketing and advertising strategies, they have gained a symbolic value that often overshadows the sad reality of the miserable and short existence that the overwhelming majority of them lead.2Concerning the treatment of food animals in industrial production, see the documentaries Slaughterhouse: What the meat industry hides or Dominion . What we consider to be the inherent value of nonhuman animals’ lives permanently fluctuates. But the question we have to ask ourselves may not be if animals are valuable beings, or what makes their lives valuable; but rather, through which mechanisms and through which framings do we discuss and decide these changing values.

An analysis of representations of animals on social media—and especially of farm animals—can provide an interesting insight into how the content posted on these platforms reactivates and reinvents old literary strategies of anthropomorphisation and ostracisation of animals. The following insight will focus mainly on the cultural construction of the moral value of the nonhuman world, and how this understanding feeds into and justifies its economic and political values in contemporary market and consumer habits. This insight examines critically the assumptions of mainstream welfarist views and the moral value they assign to animals, by considering their death as a necessary and morally acceptable evil as long as their lives are “good”, without ever specifying what a “good life” truly means.

Social media as a contemporary platform for moral reflection

The legitimacy of Western meat-based food habits, as well as the impact of these habits on our living environment, is being increasingly called into question. It seems that the vertiginous collapse of life on earth we are currently experiencing, which also threatens the very survival of humankind, has added a new dimension to an ongoing problem of morals and ethics: should we kill, eat, and exploit nonhuman animals? Since the late eighteenth century, rising concerns about animal welfare have been reflected in a growing corpus of literature devoted to the establishment of a new ethical and legal status for animals. This branch of moral philosophy, ranging from Bentham’s utilitarianism to more recent abolitionist approaches, has sought to evidence the inherent moral value of nonhuman lives, even as it disagrees on the consequences that may be derived from these conclusions .

However, two centuries of discussions on animal welfare have not prevented the deterioration in the conditions of animal husbandry and the boom in global meat consumption, especially since the 1990s. As Frank Kupper and Tjard de Cock Buning note, the search for absolute foundations and truths concerning the value of animal lives still fails to grasp fully the way in which morality is experienced by situated communities . Referring to John Dewey’s philosophical pragmatism, they argue for a resolution of morally problematic situations based on the public deliberation of shared values. The “value labs” they established in the Netherlands are conceived as trustworthy, non-threatening environments, where participants are invited to take part in an in-depth exploration of moral issues related to animal welfare . In other words, these labs recreate and improve the conditions of a public discussion usually taking place within wider cultural and social frameworks. They are idealised re-enactments of the societal mechanisms at play in the assignment of a certain value to different categories of nonhuman beings. Most of these mechanisms unfold and develop in two main areas: cultural production and social media.

According to a survey conducted in 2019 in the UK, most people who have decided to become vegan have taken this decision after having watched a documentary, seen a video on social media, or read articles or books on the topic.3This survey was conducted by the activists of the Vomad Community in 2019. The influence that social media has on the formation of the consumer’s opinion is a well-known process. Many young people have first come into contact with feminist or anti-racist theories through short posts shared on activist accounts; on the other hand, the filter bubbles created by the algorithms of social media platforms prevent users from being confronted with content that might challenge their beliefs. Social media channels offer amazing opportunities for discussion, but they also, paradoxically, constrain more broad-minded approaches to certain themes, since they seem to increase disagreement in society by encouraging the radicalisation of pre-existing beliefs . Interestingly enough, these platforms are full of images and videos of animals. From star pets to accounts dedicated to certain species or animal activities, our feeds are filled with nonhuman beings, which are often the only animals we see in daily life. The reactions these images provoke, when not limited to expressions of joy and tender emotion, echo centuries-old debates on the animal condition: are they happy? Are they in danger? Is it normal to exploit them by making them a source of entertainment? Is this natural? Through these exchanges, users can measure, question, and reform their perceptions of nonhuman animals. What is at stake here is the emotional, economic, social, ethical, and aesthetic value with which they imbue the animals.

Though these discussions have taken a more immediate and polemical dimension through the rise of social media, they have been present for a long time not only in academic spheres, but also and above all in popular culture, where the question of the relationship between human and nonhuman animals is constantly being reactivated. Youth culture, in particular, has thematised and romanticised the paradoxes of our love-hate relationship with wild and domestic animals, and often resulted in the complete eradication of the sufferings that this relationship implies. Significantly enough, literary and cultural works featuring (farm) animals as protagonists have been marginalised within both literary canons and literary studies. Writing on animals has signified writing for less prestigious audiences, like women or children, since animals, supposedly, belong to a less prestigious category of earthly beings than humans. In the same way that moral valuations of “things” and “beings” impact cultural productions, these cultural productions also shape the processes of valuation. Indeed, as Hanna Meretoja wrote:

Literature does not merely illustrate pre-given ideas and values but also functions as a medium of thought and imagination in which questions of what is valuable for us and how to understand the value of literature are articulated from new perspectives and addressed in an open process of exploration.

This remark can certainly apply to all sorts of cultural productions, at a time when literature has lost its cultural centrality and other mediums have gained significance in the cultural landscape, shaping our social imagination in multiple ways.

The representation of farm animals that have been produced and conveyed through cultural artefacts, starting with literary works, continues to nurture contemporary discussions on animal husbandry and welfare. In particular, the different framings developed in modern and contemporary mass culture are still at play in the presentation of images and videos of farm animals that fill social media feeds. Building on Naomi Wells’s invitation to ‘take social media seriously as cultural texts’ , this short insight will focus on the diverse strategies of communication and representation at play in TikTok animal videos, in order to highlight the way in which farm animals can easily shift from one value category to another. As Wells points out, working with social media challenges humanities scholars’ traditional methodological approaches: under which conditions do these platforms allow us to conduct distant readings ? How do algorithms shape our perceptions of given communities? How can we work with—and archive—a constantly changing sample of data? This insight does not aim to solve these complex and important issues, but will appraise the many ways in which social media can perpetuate, reshape, and challenge our views of the natural world.

The videos and comments presented here are the result of a series of searches led from Berlin between 2022 and 2023, on different devices, with newly created TikTok accounts, in the hopes of reducing the impact of previous searches in the use of tags. A series of keywords (diverse farm animals, animal products like “meat” and “milk”, and vocabulary related to farming activities) have been used as search terms several times, on several devices, with different accounts. For each search, I examined and compared the most popular posts in order to identify bigger trends. The comments quoted here have been selected to reflect as accurately as possible a broader spectrum of reactions, ranging from empathy to the pleasurable consumption of images of violence. This sample of data, which mainly reflects the imaginations of a certain part of the Western population covered by our algorithm, is not the result of rigorous quantitative research: such an undertaking is beyond the scope of this paper, but would certainly benefit from being carried out to account for situated and singular value attribution practices. The following categories illustrate a non-exhaustive number of popular trends concerning farm animals, which essentially apply within the cultural context of Western Europe and North America.

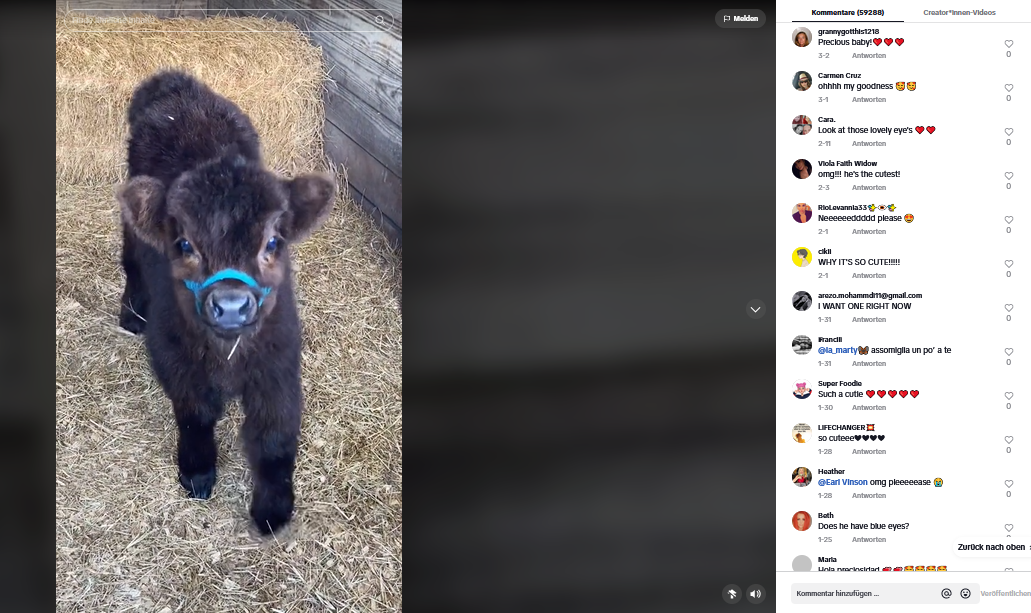

‘Cows have the prettiest eyes’: the cutest, the worthiest?

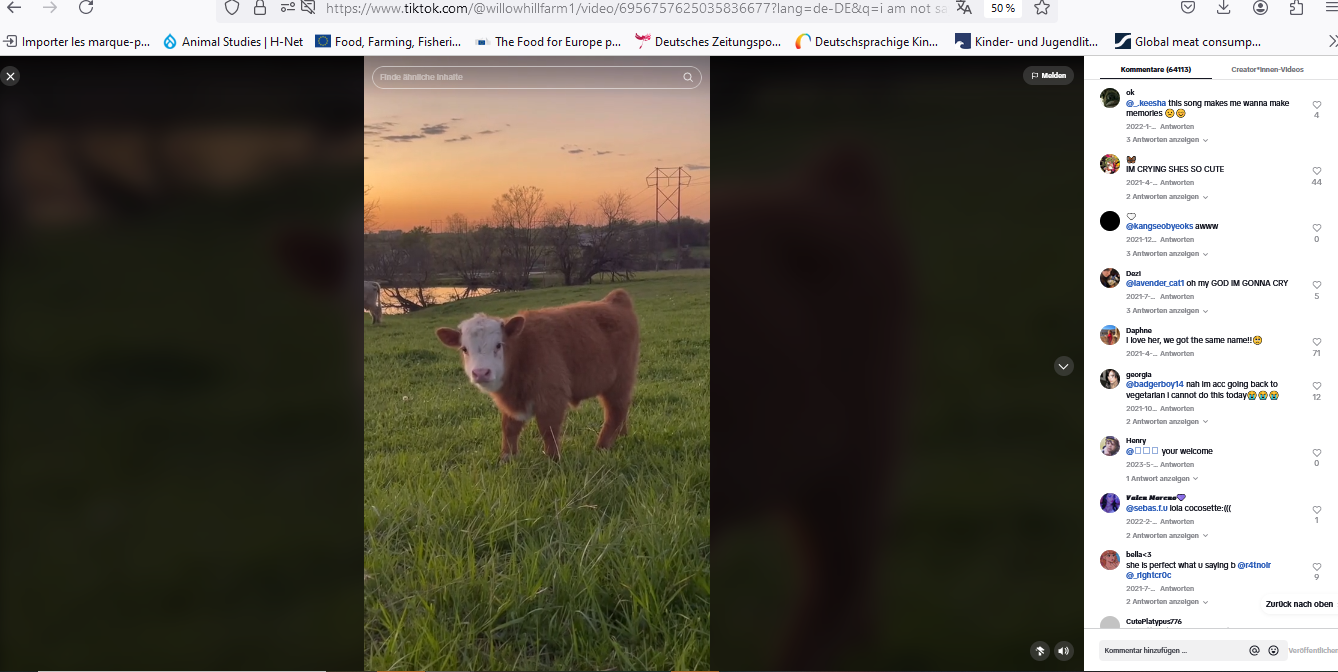

As is the case for other animals, although in a smaller proportion, farm animals on TikTok are predominantly “cutified”. Admittedly, some of them appear on the platform as already transformed and cooked products and rarely get to be represented as living beings—if one were to type ‘chicken’ or ‘turkey’ in the search field, the large majority of the resulting reels would be cooking videos (Search: #chicken, 14.09.234See here. The reader should be aware that comments on TikTok posts are not permanent and can change rapidly.). The “cutification” of farm animals is mostly restricted to mammals. Cows, pigs, sheep, and rabbits are pictured playing, cuddling, looking for human attention, or interacting with other species. They appear sleeping inside human homes, being petted while climbing on a sofa or lying peacefully on a carpet. Most of these cute framings present the viewer with smaller versions of farm animals: mini-pigs, mini-cows, and lambs, which are very much like usual pets and behave in a similar way. Having become sweeter and more receptive to human solicitations, farm animals live in the world of farming and enter a more privileged sphere, where they are treated as valuable companions.

These videos generate mixed reactions: some viewers marvel over their cuteness, and often express indignation or regret when reflecting on their own eating habits (‘Fudge it! I’m vegan now. 🌱😭’ (User: Fadz, on: knucklebumpfarms, ‘Good Morning Homer’, video, 01.04.22 https://www.tiktok.com/@knucklebumpfarms/video/7081413490262412586?q=Good%20Morning%20Homer&t=1716805994682); ‘So happy I’m not eating that anymore’ (User: Anna, ibid), ‘nah im acc going back to vegetarian i cannot do this today😭😭😭’ (User: georgia, on: willowhillfarm1, ‘I’m not saying she’s perfect, but Daphne is as close as it gets.’, video, 30.04.21 https://www.tiktok.com/@funnyfarm1512/video/7237107208830455082?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7268257445037688352), while others—mostly male users, judging on the usernames and profile pictures of users commenting on the top ten results with the search #cow—make fun of this framing (‘Kleines Rinderhack 😅’ (User: 100lukas1, on: funnyfarm1512, ‘☺️☺️’, video, 25.05.23) ‘bro she speaks like the cow is gonna be lawyer little did she know the cow is gonna be hamburger’ (User: kpakep33, on: hayleeandhercows, ‘Rosie has always been a very picky girl 🤦♀️’, 18.03.23 https://www.tiktok.com/@hayleeandhercows/video/7212021987512782126?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7268257445037688352). In the case of bigger farm animals, like large rescued pigs, it is the incongruity of the situation that makes them cute; transplanted into a friendlier setting, they still carry with them the memory of the life they escaped and their cuteness then lies in a certain heroic vulnerability. ‘Such objects’, writes Simon May, ‘are therefore cute not despite but because of their survival in the face of their vulnerability or misfortune. If they were to collapse, shrivel, and die, they wouldn’t be cute at all’.

Can we say, then, that the cutification of animals on TikTok is an efficient strategy for making the viewer more sensitive to the value of the natural world? Do these videos somehow restore the permanent depreciation of the non-human? Most of the representations of farm animals that we encounter in everyday life are cute. The effectiveness of videos of cute animals on social media is anchored in a larger process of picturing farm animals as sweet, inoffensive, cuddly, and friendly. From youth literature to marketing techniques, the “Cute” has dominated representations of nonhuman beings, at least since 1945. Some researchers have argued that the humanisation of the natural world through its “cutification”—and consequent association with human offspring—has allowed a deeper identification with animals and the development of a more empathic relationship with the non-human . More often, it has been demonstrated that the proliferation of cute representations of animals advanced the exploitation of the natural world, and that cuteness annihilates otherness by extending human logic to other ways of existing (see ; ). The Cute would, thus, always involve a hidden part of domination and abuse. Nonetheless, social media, whilst partly reproducing these strategies (for example, by presenting animals in a situation of stress or despair as a touching expression of affection for their human owner), may encourage the viewer to think beyond this paradox.

In youth literature’s bestsellers, the farm is pictured as a modern Arcadia, free of any mention of violence and exploitation, where humans and nonhumans happily work together. In advertisements for human products, animals are willing to give their lives and working force to benevolent consumers. In TikTok cute Reels, although this conception of farm work is still largely active, the focus lies on the idiosyncrasy of the animal featured (see search #cow https://www.tiktok.com/search?q=cow&t=1694685866281 : among the many “cute videos”, most of them present head shots of cows interacting with their owner, with their names often indicated in the description). One cannot avoid the confrontation with the reality of the animal’s feelings and agency. Certainly, this does not mean that the viewer will become vegan the minute they open their TikTok feed; but rather, that the display of cute videos on social media might trigger ambiguous and contradictory responses. On the one hand, they fall within a long tradition of individualisation of mass-exploited animals, which paradoxically justifies this exploitation by differentiating between the value of some “special” animal characters and other anonymous, insignificant lives (not all of them are so cute and affectionate; I don’t eat these ones). On the other hand, they force the viewer to acknowledge the very existence of a sensitive, intelligent being within a body they are accustomed to dismissing.

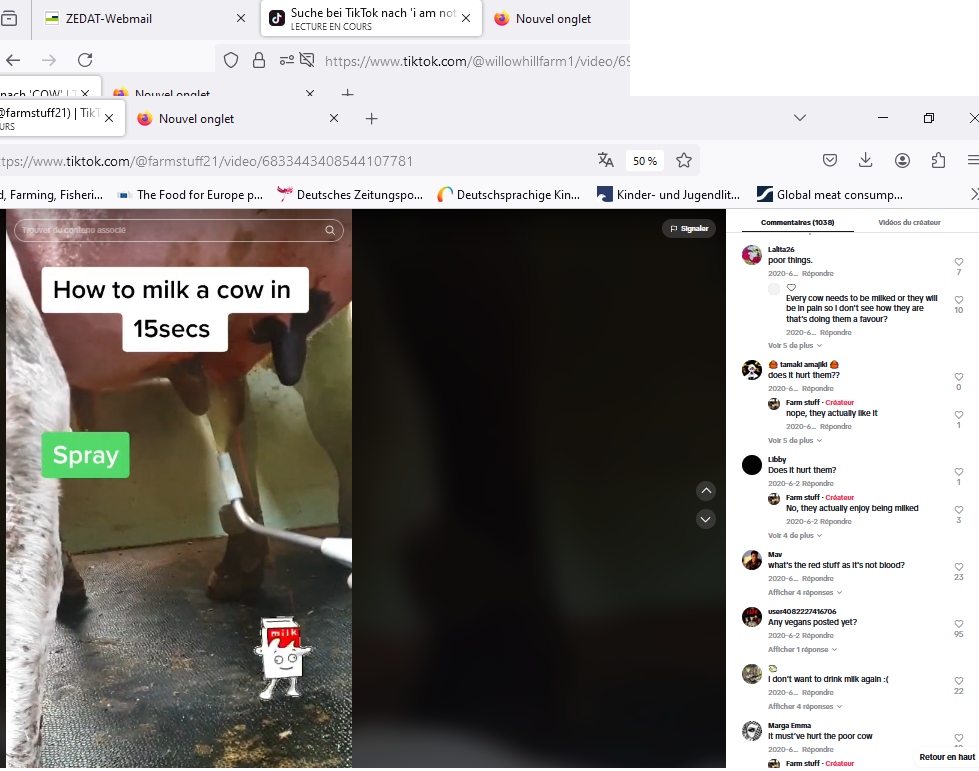

‘All farmers care for cows’: debating the legitimacy of the milk industry

The main trend competing with cute images of farm animals, especially when it comes to cows, consists of Reels staging the “real life” of cows in dairy farming. These very popular videos, mostly posted by North-American farm owners and commented on by North-American users, show the farmers themselves explaining to their audiences that their animals are doing perfectly well and debunking what they call “vegan myths”, using depictions of their daily work. Cows, they say, are also happy indoors, like being milked, are not separated from their calves, and live a long and happy life. The comments under this kind of video exceed the usual oppositions between convinced vegans and supporters of the dairy industry. Lots of commenters wonder about the cows’ feelings, like in the comments taken from a Reel entitled ‘How to Milk a Cow’: ‘doesntt the power wash hurt the cow it bleeding😭😭evil people drink water😢😢😢😢’ (User: ariana_4_ever, on: farmstuff21, ‘how we get milk from the cows’, 01.06.20 https://www.tiktok.com/@farmstuff21/video/6833443408544107781?is_from_webapp=1&web_id=7268257445037688352); ‘Im not vegan but cows are meant to be milked, by their children not humans’ (User: _m._a_l_a_k_, ibid). Other answers to these comments include: ‘If you didn’t take the milk, the cows would be in pain’ User: Anita84, on: dr3wmeister, ‘please educate yourselves vegans’, 30.11.20 https://www.tiktok.com/@dr3wmeister/video/6900949681308716289), ‘milk cows HAVE to be milked. If you’re a mother you know too much milk is uncomfortable’ User: tellastoryjackanory, ibid). The discussion focusses on the well-being of the animals, as well as on their consent. Do cows enjoy being here? Interestingly enough, this shows that the very fact that animal lives do have an inherent value is not being called into question. Cows deserve good living conditions—the question is what this means. The traditional Western utilitarian thinking of animal welfare is easily recognisable here: animals can be exploited and killed if they do not suffer. What suffering really means remains unclear.

These farming videos spread a clear message: the myths about animal husbandry promulgated by animal welfare activists are based on biased facts and all farmers do care for their cows (and more generally, for all their animals). Some of these videos even show images of intensive industrial farming with a cheerful musical background, which aim at demonstrating that animals do not suffer from the mechanisation of farming practices, and that having a larger herd does not mean that their living conditions deteriorate. The actual death of the animal is not addressed. No mention of the slaughterhouse is made. This, as well, conforms to Bentham’s conception of animal welfare, which postulates that the killing of animals can comply with their actual well-being. In accordance with Bentham and his followers, the question is not whether animals are capable of reasoning or communicating, but rather whether they are capable of experiencing pain . Consequently, utilitarian thinkers assume that slaughter does not result in pain and that animals can be ethically killed and consumed.

These very popular videos provide the viewer with a comfortable justification for their food habits. Reassured by peaceful images that match the widely shared conceptualisation of animals as entities ‘occupying a space between persons and things’ , viewers can easily forget the accusations made on ethical and environmental grounds against the dairy industry. The strategies developed by these farmers on social media are made very successful by the “magic trick” they perform in presenting the contradictions haunting animal farming: they demonstrate to the viewer that the intention is to take care of farm animals, to give them a life worth living, which results in the transformation of cows into an economic product. Farmers would, then, happily benefit from this original act of grace.

This rhetoric directly aligns with the representations of the animal farm held by Western urban dwellers, especially in narratives aimed at children. As Stacy Hoult-Saros points out, ‘nowhere is the denial of human cruelty and culpability in the transformation of living animals into commodities more pronounced than in farmed animal stories for children’ . In these stories, animals accept with gratitude the conditions of their exploitation and conversion into convenience goods. The same tale is taken up by the TikTok trend of dairy farmers who profitably manage to mask the devaluation of farm animals’ lives under the guise of a rhetoric of care and interspecies mutual aid.

‘Love them, don’t eat them’: restoring the human-animal bond

Accounts held by owners of shelters for rescued farm animals constitute the direct counterpart of content produced by farmers. These videos preach to the converted and generally receive a relatively homogeneous range of comments, which mainly congratulate the owner on their work and praise the cuteness of the animals. Just as in the dairy industry reels, they focus on tender interactions between humans and animals. Animals are filmed while being fed, running toward their owner when called by name, asking for attention, playing, or cuddling. The focus lies on the sweetness and cuteness of animals, often playing on the same mechanisms as other videos posted by different owners featuring farm animals acting like pets or children. The intention is to provoke an empathic emotional response that leads to the complete recognition of the irreducible value of nonhuman lives. However, this strategy is not entirely free from contradictions.

Hence, a wide majority of this content first consists of the idyllic staging of human lives entirely devoted to a high moral cause—the saving and sustainment of innocent creatures that depend entirely on them. Virtually none of these videos present the animals living their lives away from human eyes. Even in these ultimate attempts to restore animals as independent, complete, valuable beings, non-human beings are still framed within their relationship to humans. As shown by Randy Malamud, representations of animals in visual culture are always extremely ambivalent, for they always imply a possibility of exploitation and domination—which would mean, Malamud suggests, that the only way to break entirely free from the casting of animals as powerless living resources would be to stop trying to observe and represent them at all costs . The communication strategies developed by shelters echo those of animal welfare activists: they seek to prove that animals deserve to live because they are “just like us”. By taking good care of our weaker co-beings and refusing to kill them, we demonstrate a higher degree of morality. In the end, the value of animal lives captured by these videos remains relative: they are worth being protected if they are seen and acknowledged by human eyes.

‘It’s called the food chain’: evolutionary myths of human superiority

More sporadically, farm animals also appear in an atypical subgenre of animal videos: scenes picturing an easy prey being violently devoured by animal predators. These images, classified as potentially shocking for sensitive users, are commented upon extensively by male users, who lay claim to the necessity of such events; see, for example, the comments on a widely shared video of a zebra being eaten alive by a crocodile, which acknowledges violence as a necessary part of the food chain and clearly enjoys making fun of the show (User mejoberry1: ‘Watch the crocodile get cancelled!’ https://www.tiktok.com/@wildlife_99_vn2/video/7252480166042012954?q=zebra%20crocodile&t=1694687486835). Parallels are easily drawn between human dietary habits and the animal kingdom (User Alex_Re: ‘And some of us complain about food from animals that have been killed with no harm xse’), with ‘Nature’ being perceived as an ethical justification for situated cultural habits, such as hunting or eating fast-food. The rare empathic reactions appearing in these comments mainly go to dogs and cats being attacked by wild animals, rather than other wild animals or farm animals.

These specialised accounts remain quite uncommon, but they gather a consequent number of followers and represent an important component of the legitimation of violence against and exploitation of all kinds of animals. Valérie Chansigaud’s work on the role of animals in children’s culture has highlighted that our appetite for narratives of predation results from an anthropomorphic projection on the actual lives and deaths of animals, which also encompass diseases, pests, difficult environmental conditions, and lack of resources . We like to think of predation as the main cause of animals’ death, for it comforts us in the carnist ideology that spread widely from the end of the nineteenth century and that builds on the idea that meat is ‘necessary, normal, natural’ . TikTok videos showing animals attacking their prey assure the viewer that they (or he, for these accounts mostly address their users as males, as do the comments) belong to the top of the food chain and can comfortably watch these scenes while laying on their sofa and biting into their burger. This content strengthens the feeling of dominating a pyramidal hierarchy of living creatures, whose exploitation for the sake of humankind is made justifiable. It lends credence to the dismissal of animal existences and encourages their framing as insignificant, though useful elements of a world all made for and by humans.

Conclusion

The multiple framings in which farm animals appear in TikTok Reels build on existing categories of value, which may overlap and involve paradoxical conceptions of animal welfare. The strategies established by different stakeholders (animal owners, farmers, shelter workers) reactivate deeply rooted understandings of the human-animal relationships and open a space for discussion that, although of limited efficiency when it comes to the complete reconsideration of an opinion, allow users to confront their views. The question that I have tried to address, however, was not that of the potentialities of social media in promoting or undermining animal welfare ideologies. What is particularly interesting is the way in which social media content reflects collective perceptions of the worth of different categories of animals, including the circumstances and spaces in which these perceptions are formed. These collective perceptions are the result of the long accumulation of complex projections onto, and representations of the so-called natural world. Identifying these biases in everyday social devices like TikTok allows us to identify the most recent developments of contemporary sensibilities towards nonhuman beings and to understand more fully the shared filters through which we assign changing values to our earthly co-habitants.