Abstract

This text shows how the circulation of German-language historical novels connected readers from different parts of the world during the nineteenth century. This is achieved through a case study based on the circulation of the works of Carl Franz van der Velde (1779–1824), an author who wrote historical novels in German. Public library catalogues, newspaper advertisements and reviews published in nineteenth-century periodicals are used as sources. I conclude that van der Velde’s novels underwent hundreds of editions in the nineteenth century, were favourably received by literary critics and served as an instrument of education in European countries such as France, England and Portugal, as well as beyond the Atlantic in Brazil.

The value given to particular books, authors and literary genres can change greatly over time. Within Cultural History research, several studies have been developed with the objective of better understanding these changes, taking into consideration the context in which the books were produced and their materiality (see ; ), Roger Chartier , for example, proposes a History of Literature that considers the forms of canonisation of books, the context in which they were produced and the ways they were read. According to this author, works ‘have no stable, universal, fixed meaning. They are invested with plural and mobile significations that are constructed in the encounter between a proposal and a reception’ and ‘any work inscribes within its forms and its themes a relationship with the manner in which, in a given moment and place, modes of exercising power, social configurations, or the structure of personality are organized’ .

A literary analysis that considers these aspects makes it easier to understand the importance and different meanings of a book in the period in which it first circulated among readers. Moreover, recent studies on the circulation of novels in the nineteenth century have shown the existence of a transatlantic circulation of printed matter, which connected readers from distant parts of the world and allowed books to be read similarly in different countries and continents (see ; ; ). One literary genre whose evaluations have varied over time, space and social configurations is the historical novel. Particularly relevant in the first half of the nineteenth century, this type of narrative did not receive much attention within some Histories of Literature, and many authors who had been successful in past centuries are no longer read or published today (see ).

Although narratives with historical themes have existed since the Middle Ages, it was between the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries that novels containing the characteristics currently associated with the genre were published . György Lúkacs associates the emergence of this type of narrative with the revolutions experienced by European nations between 1789 and 1814, which accelerated social transformations and reinforced the feeling that ‘there is such a thing as history, that it is an uninterrupted process of changes and finally that it has a direct effect upon the life of every individual’ . This occurred especially in German territory:

in the Sturm und Drang, the problem of the artistic mastery of history already appears as a conscious one. Goethe’s Götz von Berlichingen not only ushers in a new flowering of historical drama, but has a direct and powerful influence on the rise of the historical novel in the work of Sir Walter Scott.

According to Hans Vilmar Geppert, it is not possible to associate the beginning of the genre only with Scott’s books: long before the publication of Waverley, authors such as Achim von Arnim and Alfred de Vigny had already published books with characteristics of this genre, which could also be considered as ‘the first historical novel’ .

Regardless of its origin, this genre flourished in the first half of the nineteenth century and, for some decades after Götz von Berlichingen’s publication, historical drama continued to be written by leading authors, several of whom, such as Alessandro Manzoni and Victor Hugo, also wrote historical novels . These books, which connected historical events and literary fiction, had the aim of representing the facts of history by bringing past events to life, interpreting what has happened in these events, and being themselves a part of the History . They were seen especially as a source of entertainment and education, which increased their circulation.

In German territory, the historical novel was very relevant within the book market, which was expanding in the first half of the nineteenth century: ‘never before had so many books been written, published and offered to the reading-hungry public in the lending libraries that were appearing everywhere’ .1‘Nie zuvor wurden so viele Bücher verfaßt, verlegt und in den aller Orten entstehenden Leihbibliotheken dem lektürehungrigen Publikum angeboten’ . My translation. According to Kurt Habitzel and Günter Mühlberger, ‘1830 saw as many historical novels as any year in the nineteenth century’ and ‘in the 1820s and 1830s the public’s desire for historical works of entertainment was so strong that even eighteenth-century authors were widely read’ .

This public preference boosted the publication of historical novels in the following years:

In the decades up to the middle of the century, during the era of Walter Scott and his imitators, a little more than a thousand German-language historical novels were published, according to the latest calculations, which represents about half of the novels produced in the period. 2‘In den Jahrzehnten bis zur Jahrhundertmitte, der Ära Walter Scotts und seiner Nachahmer, erschienen nach neuesten Zählungen etwas mehr als tausend deutschsprachige Geschichtsromane, der durchschnittliche Anteil der Gattung an der gesamten zeitgenössischen Romanproduktion beträgt etwa die Hälfte’ . My translation.

The increase in the production of this type of narrative has made some authors stand out. The most prominent novels in lending libraries located in the German-speaking territory were those written by Carl Spindler, Caroline Pichler, Carl Franz van der Velde and Wilhelm Hauff .

Among these authors, the example of van der Velde is of particular interest, because it indicates the relevance that the historical novel had within and outside the German-speaking territory and about the reception of works of this genre.

The reception of van der Velde’s novels within the German-speaking territory

Van der Velde was born in 1779 in Breslau. In 1797, he began studying law at the Universität Frankfurt and throughout his life he worked in courts in other cities, such as Winzig and Zobten . In the first decade of the nineteenth century, he started to publish some of his first novels and, in 1817, he became a contributor to the newspaper Dresdner Abend-Zeitung, printed in the city of Dresden and edited by Theodor Hell (pseudonym of Karl Gottfried Theodor Winkler). In this periodical, which devoted several of its sections to the analysis and publication of literary texts, van der Velde published more than 15 novels in serial form. Many of these were later sold in book form by the Arnoldischen Buchhandlung, which was also responsible for printing the newspaper.3For a list of the twenty novels van der Velde published during his lifetime, see .

According to Theodor Hell, the first narrative published in the newspaper Arel: eine Erzählung aus dem dreißigjährigen Kriege [Arel: a tale from the Thirty Years’ War] was already successful, and van der Velde was pleased with its reception among readers:

The tale had not deceived my expectations, and also immediately made a […] pleasing impression in general. For him, the gratitude of his friend, as well as the applause of numerous readers of the Abendzeitung, was most gratifying and encouraging. 4‘die Erzählung hatte meine Erwartungen nicht getäuscht, und machte auch allgemein sogleich eine […] erfreulicheu Eindruck. Für ihn war der Dank des Freundes, wie der Beifall der zahlreichen Leser der Abendzeitung, höchst erfreulich und aufmunternd’ . All translations of the letters and critical texts mentioned in this text are my own.

Van der Velde was aware of the success of his narrative and, in October 1818, wrote to Hell: ‘my tales in the Abendzeitung had a success I never expected’ .5‘meine Erzählungen in der Abendzeitung haben einen Erfolg gehabt, wie ich ihn nie erwartet’ .

The tales and novels he published in the following years were also well received by the public, and soon his name became better known. In the 1820s, many of his books were mentioned in advertisements and critical texts published in literary journals, such as the Leipziger Literaturzeitung (1800–1834) and the Jenaische Allgemeine Literaturzeitung (1804–1841). In 1820, an edition of his complete works was published by the Arnoldischen Buchhandlung and announced in the Leipziger Literaturzeitung. This advertisement was accompanied by a long critical text, in which the qualities of van der Velde’s novels were mentioned:

He knows how to use details borrowed from history and descriptions of the earth in the most skilful way to characterise the countries and times, so that one receives a vivid picture of their peculiarities, which in itself arouses no small interest due to its deviation from what we are used to. 6‘Er weiss die aus der Geschichte und Erdbeschreibung entlehnen Einzelheiten auf das geschickteste zur Charakteristik der Länder und Zeiten zu benutzen, so das man von ihren Eigenthumlichkeiten ein sprechendes Bild erhält, das schon an sich vermöge seine Abweichung von dem, woran wir gewöhnt sind, ein nicht geringes Interesse erregt’ .

The quality of the descriptions of historical facts and characters was a point almost always mentioned in critical texts about van der Velde’s work. Another aspect highly valued in his work was the construction of characters: ‘The narrator […] does not lack the gift of portraying his characters in their particular idiosyncrasies, and of classifying them appropriately according to their differences’ .7‘Es geht dem Erzähler aber auch die Gabe nicht ab, seine Personen in ihrer besondern Eigenthümlichkeit darzustellen, und sie nach ihren Verschiedenheiten gehörig bey- und unterzuordnen’ .

Another aspect mentioned in a review published in 1821 is the author’s style: ‘as wonderful and adventurous as the whole structure of this novel is, the author’s presentation is so graceful, the style so light and correct, that we can recommend it as an entertaining read’ .8‘So wunderbar und abentheuerlich nun auch das ganze Gewebe dieses Romans ist: so ist doch des Vfs. Vortrag so anmutig, der Stil so leicht und correct, dass wir ihn als eine unterhaltende Lectüre empfehlen können’ . His style was also praised in a text published in 1821 in the Leipziger Literaturzeitung:

Prinz Friedrich, eine Erzählung aus der ersten Hälfte des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts belongs to the so-called historical novels. It is based on the story of the well-known Baron Neuhof […] The author gives him a son and crown prince whose adventures of love and war are now told here in a rather entertaining way, in a style full of life and spirit. 9‘Prinz Friedrich, eine Erzählung aus der ersten Hälfte des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts, gehört zu den sogenannten historischen Romanen. Ihr liegt die Geschichte des bekannten Baron Neuhof […] Der Verf. gibt ihm einen Sohn und Kronprinzen, desses Liebes- und Kriegsabenteuer hier nun auf eine ziemlich unterhaltende Weise in einem Style voll Leben und Geist erzählt werden’ .

The examples mentioned indicate that van der Velde’s books were understood in the first half of the nineteenth century as part of the genre of the historical novel and that they were evaluated according to a set of specific criteria, such as the description of places, the good use of historical facts within the narrative, the style and their ability to entertain the reader. Another characteristic often attributed to his books is their didactic function, which is mentioned in the following comment:

The public has decided on the value of this author, and he fully deserves the great acclaim he has received. Rich inventiveness, vivid and powerful portrayal of characters and situations, a cheerful, light, flourishing style, all this combined with a pure and deeply feeling mind, secures the author one of the first places in this field of poetry. The story Die Lichtensteiner has, apart from all this, quite excellent moral values. 10‘Das Publicum hat über den Werth dieses Erzählers entschieden, und er verdient den ihm gewordenen grossen Beyfall vollkommen. Reiche Erfindungsgabe, lebendige und kräftige Schilderung der Charaktere und Situationen, heiterer, leichter, blühender Styl, Alles dies zu einem rein und tief fühlenden Gemüth gesellt, sichert dem Verf. einen der ersten Plätze in diesem Gebiet der Dichtung. Die Erzählung: Die Lichtensteiner, hat noch, ausser diesem Allen, ganz vorzüglichen moralischen Werth’ .

These criteria for evaluating novels were not only used in German-speaking territory. Márcia Abreu studied the critical texts published in newspapers from England, Portugal, Brazil and France in the nineteenth century and noted that critics in these four countries evaluated novels in very similar ways: besides instructing, entertaining and moralising, they expected that a novel’s style be neither affected nor declamatory, but rather easy and gracious; that it uses clear, elegant and unpretentious language, which should not be overly refined. Their expectation was that the plot reveals a good invention through the suitable choice of episodes and is presented in an orderly and cohesive fashion, free of forced and unnatural passages, avoiding digressions and tangents from the central point, leading to a surprising, yet plausible outcome, without resorting to any supernatural tricks. Furthermore, the expectation was that the characters be similar to ordinary people and express themselves according to their situation and character. This ensemble was to produce a narrative that awakens emotion and compassion in its readers .

The didactic function of the narrative was also important to these literary critics:

One of the more frequently used criteria was in gauging the text’s morality, since everyone, and not just conservatives, aimed to assign a purpose to reading and believed that it always provoked an effect in the reader. Committed to Horatian principles, they expected a combination of instruction and pleasure, associated with moralizing, which would be achieved through plots in which vice would be punished and virtue awarded.

One possible explanation for the common strands in the way fiction was interpreted and evaluated in distant places with strong social differences could be the ‘existence of a shared literary education, anchored in the study of rhetoric and poetics, which operated in different countries, as well as journals that published recent reviews on contemporary novels’ .

Therefore, the similarity between the evaluations of van der Velde’s books published in newspapers such as the Leipziger Literaturzeitung and in those published in other countries, such as France, Portugal and Brazil, are indicative of the circulation of books and ideas in the nineteenth century, which allowed readers from different countries to read novels in a similar way. Authors of historical novels, such as Walter Scott, were part of this process and circulated in different regions and continents, allowing people from various parts of the world to come into contact with this type of narrative and to understand the criteria that should be used to evaluate it (see ).

Scott’s novels began to be translated into German in 1817 and soon became accessible to readers in German-speaking territory, such as van der Velde. Scott was mentioned very positively in van der Velde’s letters to Theodor Hell, in which he shows his admiration for the Scottish author: on November 12, 1821, for example, he wrote to Hell:

Now I have also read Walter Scott’s Kenilworth. All respect! I will emulate him on that. What colourfulness and truth in the descriptions, what characterisation, what entanglements! […] I can hardly remember a Lecture that has captivated me like this. This Kenilworth alone is worth the Order of the Bath. 11‘Jetzt habe ich auch Walter Scotts Kenilworth gelesen. Allen Respect! Das mache ich ihm nach. Welche Farbenfülle und Wahrheit in den Schilderungen, welche Charakteristik, welche Verwicklungen! […] Ich wüßte bald nicht, daß mich eine Lectüre so hingerissen hätte. Dieses Kenilworth ist allein den Bath-Orden werth’ .

It is interesting to notice that van der Velde’s comments on Scott’s novel are based on the same criteria that were used in the newspapers to evaluate his own work: he admires the descriptions, the construction of the plot, the characters and the book’s ability to entertain the reader. Perhaps this was the reason why he wanted to copy some of the techniques used by the Scottish author: he may have imagined that his work would be evaluated in a similar way by literary critics and that it would be read by people with similar taste. In many reviews, comparisons were made between the works of the two authors, as in the following text published in the Leipziger Literaturzeitung: ‘we have before us a whole series of writings by the man who competed with the great Scotsman […] for the prize of who best understood how to transfer Romanticism into the realm of the historical’ .12‘Eine ganze Reihe von Schriften des Mannes liegt vor uns, der mit dem grossen schottischen […] um den Preis rang, wer am besten verstände, die Romantik ins Gebiet des Historischen hinüber zu spielen’ . In the author’s opinion, van der Velde should win this prize, because he had

the advantage of diversity over W. Scott. Each of his novels is set in a different time, in a different country, and even the strictest judge must admit that language, colouring, costume are appropriate to the country, the time, the people. How poor, on the other hand, appears W. Scott, who only ever chooses, with a few exceptions, his Highlands and England as the scenery, on which most of his own countrymen then move according to the way the well-studied Edinburgh Chronicle has sketched them out for him. 13‘Er hat vor W. Scott die Mannichfaltigkeit. Jeder seiner Romane spielt in einer andern Zeit, in einem andern Lande und auch der strangste Spitterrichter muss zugeben, dass Sprache, Colorit, Costüme, dem Lande, der Zeit, dem Volke angemessen sey. Wie dürftig erscheint dagegen W. Scott, der nur immer, geringe Ausnahmen abgerechnet, seine Hochlande und England zur Scene wählt, auf welche sich dann meist seine eigenen Landsleute nach der Art bewegen, wie sie ihm die wohlstudirte Edinburger Chronik vorgezeichnet hat’ .

Comparisons between Scott and van der Velde (and opinions on who would be the better writer) varied greatly over time. Since this text was published in a bookstore advertisement, its author would probably have been keen to describe the most positive aspects of van der Velde’s novels. However, examples like this may reveal characteristics of the reception of van der Velde’s books in the German-speaking territory, such as the importance of the diversity of places and periods that he inserted in his novels, as well as the appreciation of his capacity to unite historical facts and fiction.

The international circulation and reception of van der Velde’s novels in the nineteenth century

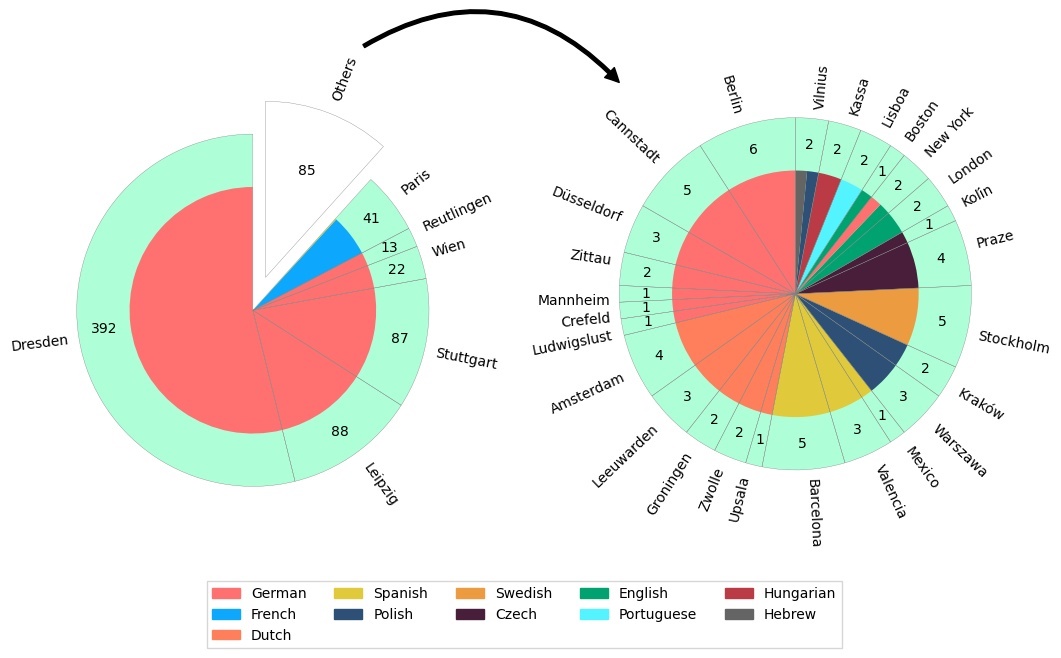

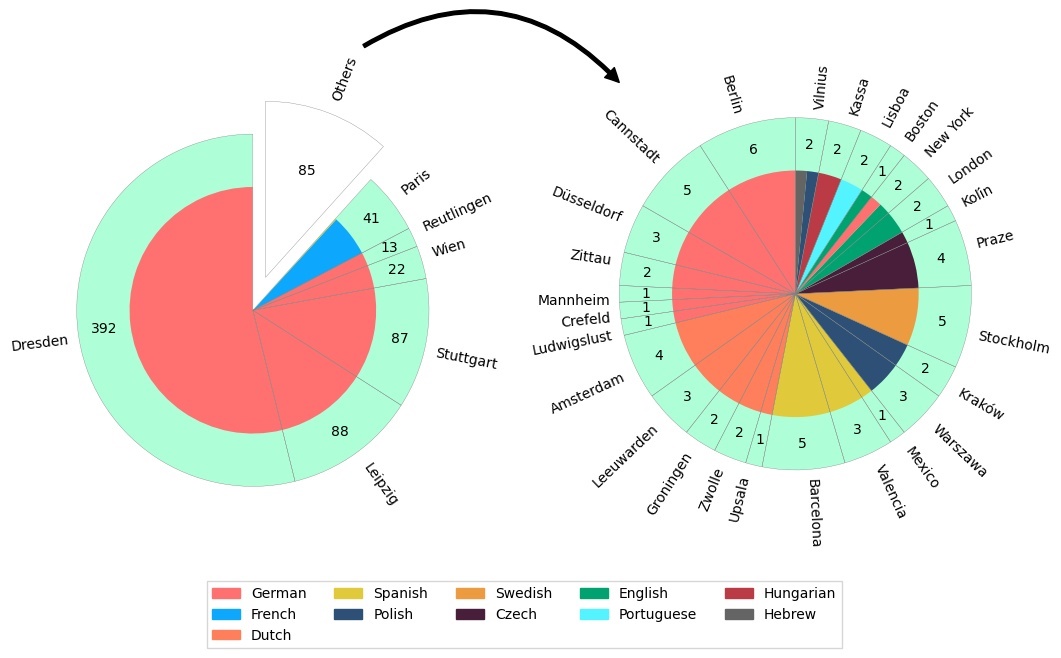

In the same period that van der Velde was asking his publisher for Scott’s novels and was having his work evaluated by critics within the German-speaking territory, he continued to write and publish books, which underwent many editions and translations, as can be observed in the following graphic:

Throughout the nineteenth century, the twenty fictional books van der Velde published during his lifetime received more than seven hundred editions.14This data was collected on the Worldcat platform, on which libraries around the world share their catalogues. Each new publication of a title was considered as an edition. All duplicate data (same title, same place of edition, same year and same publisher) were discounted. Most of them were printed between 1820 and 1830, in the German language and in the city of Dresden. However, his novels have also been translated into many other languages, such as French, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, Polish and Hungarian. These foreign editions were mostly published outside of German-speaking territory, in countries such as Portugal, Brazil, the United States, Poland, Sweden, Spain and Russia. This indicates that van der Velde’s works were part of the transatlantic circulation of novels in the nineteenth century, which allowed readers from different regions of the world to come into contact with the same works.

Some of the first translations of his novels were made into Dutch. In 1823, a translation of Prinz Friedrich (with the title Prins Frederik) was published in Leeuwarden by Steenbergen van Goor. A year later, a translation of Die Patricier (entitled De patriciërs: een verhaal uit het laatste derde gedeelte der zestiende eeuw) was published in Groningen. In the following years, his works would be translated into other languages, such as English and French.

The circulation of new translations allowed new readers to come into contact with van der Velde’s novels, and soon more critical texts about them were written. In March 1824, a review of Die Patrizier was published in The Universal Review, or Chronicle of the Literature of all Nations:

The Patricians is by far the best fiction in any language that has hitherto been delivered from the example of the Scotch Romances. Though an imitation as to manner, yet the subject and matter are perfectly original, and what is surprising in a German novel, the characters think and act like the creatures of real life, instead of being mere puppets set forth to give utterance to the sentimental or metaphysical visions of the author.

In this text, once again van der Velde’s novel is evaluated in comparison to the work of Walter Scott. The analysis of his book is based on the same criteria mobilised in the literary reviews published in the Leipziger Literaturzeitung: the subject of the narrative, the originality of the matter and the construction of the characters. The good development of these elements, in the author’s opinion, set van der Velde apart from other German novelists, who used to describe more deeply the feelings of the people represented in the narrative, and which were usually connected to their own opinions.

This review contains translations of some passages from the novel, but Die Patrizier would receive a full English translation (entitled The Patricians) only in 1826. It was published by Georg Soane within the collection Specimens of German Romances, selected and translated from various authors. In a note that accompanied the first volume, the translator explained his idea of making a collection of German novels:

When the translator commenced this work, it was with the intention of carrying on through many volumes, and thus presenting a complete circle of German romance. In such a work, it must be obvious that much must be hazarded, for the very nature of it allows no compromise with English tastes and feelings, and demands that the several tales should be selected with reference to their popularity amongst Germans.

The translation of Die Patrizier occupies the entire first volume of the collection and the other two volumes contain narratives by Friedrich August Schulze, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Adam Gottlob Oehlenschäger and Christiane Benedicte Eugenie Naubert. Although he imagined that not all the novels and tales selected would suit the taste of the English public, Soane tried to gather works by authors who were popular in the German-speaking territory. To make this selection, he may have had contact with critical texts published in newspapers in other countries, which also circulated internationally in the period (see ; ; ).

In 1827, the novel Arwed Gyllenstierna: eine Erzählung aus dem Anfange des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts was translated into English under the title Arwed Gyllenstierna: a Tale of the Early Part of the Eighteenth Century. This edition received a very positive review in The Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences & c., in which van der Velde’s ability to build characters and describe historical and fictional facts was, once again, praised:

This is a romance which well deserved the excellent translation it has found. Founding its interest on the affections—drawing its lessons from the failings of the human character […] Laid in the time of Charles XII, it presents a vivid picture of political crime and intrigue—relieved by other pictures of self-denial and devotedness.

The text was accompanied by an extract from the novel, in which the character Arwed meets King Charles XII, and ends with the sentence: ‘as a whole, Arwed Gyllenstierna is a stranger we bid hospitably welcome to England’ .

In the following years, van der Velde’s books would be welcomed also in other countries, such as France, Spain and Portugal. Between 1826 and 1827, a twenty-five-volume collection of his complete works was published in Paris by Renouard and Gosselin under the title Romans historiques de C. F. van der Velde. This edition was reviewed in the newspaper Le Figaro:

Finally, a talented man, Mr. Loeve-Vermars, has come to offer a more delicate meal to these hungry readers […] His translation of van der Velde’s novels arrives at a very appropriate moment. This German novelist is undoubtedly far from Walter Scott and Cooper, but he lacks neither imagination nor a certain talent in the descriptive genre. 15‘Enfin un homme de talent, M. Loeve-Vermars, vient offrir un met plus délicat à ces lecteurs affamés […] Sa traduction des romans de Van der Velde arrive dans un instant on ne peut plus opportun. Ce romancier allemand est sans doute bien loin de Walter Scott et Cooper, mais il ne manque ni d’imagination ni d’un certain talent dans le genre descriptif’ .

This text is indicative that, in France and England, Val der Velde’s books were evaluated in a similar way. In both countries, these historical novels, even if they were considered inferior to Walter Scott’s, could entertain readers and were valued for their descriptions, plot and active integration of historical facts.

The French public seems to have appreciated van der Velde’s works because, a few years later, some plays based on his books were performed in French theatres. One of these plays, based on the novel Christine und ihr Hof and entitled Christine, ou la reine de seize ans, was discussed in a text published in the newspaper Le Corsaire in January 1828:

van der Velde wrote a novel about the abdication and the loves of this Swedish queen, who was an astonishing woman […] Walter Scott has accustomed us to truer colours, to a more interesting and better developed drama; but he has few scenes more majestic than that of the abdication which is found in van der Velde. 16‘Van der Velde a composé un roman avec l’abdication et les amours de cette reine de Suède, qui était une femme étonnante […]. Walter Scott nous a habitués à des couleurs plus vraies, à un drame plus intéressant et mieux dévéloppé; mais il a peu de scènes plus majestueuses que celle de l’abdication qui se trouve dans van der Velde’ .

Two years later, the novel Die Patricier would be used as the basis for the play Nobles et Bourgeois, performed at the Théatre Royal de l’Odéon. In a review of the play, the author mentioned the positive aspects of the narrative:

This is one of the most remarkable works of this writer so full of descriptive verve and historical action. In this novel, we see the old feudal ambition struggling against the proud independence of the bourgeoisie: it is a reflection of those peasant revolts so well described in Goethe’s Götz von Berlichingen, and which van der Velde himself has traced in his Anabaptistes. But in order to understand these stories, it is necessary to be initiated into the customs and histories of Germania; no book has ever been imbued with more local colour. 17‘Cet ouvrage est un des plus remarquables de cet écrivain si plein de verve descriptive et d’action historique. Dans ce roman, on voit se mouvoir la vieille ambition féodale, luttant contre la fière indépendance des bourgeois: c’est un reflet de ces révoltes de paysans si bien décrites dans le Goetz de Berlichingen de Goethe, et que van der Velde lui-ême a retracées dans ses Anabaptistes. Mais pour bien concevoir ces récits, il fault être initié aux moeurs et aus histoires de la Germanie; jamais livre ne fut empreint de plus de couleurs locales’ .

This is one of the few critical texts that does not contain comparisons between van der Velde and Scott. Furthermore, its author emphasises the writer’s accurate use of the history of the German-speaking territory in his plot, highlighting the importance of the local colour of the narrative—another criteria also widely used by critics who sought a relationship between the place in which a book was written and its content (see ). Moreover, by comparing van der Velde’s novel to Goethe’s historical drama, the critic placed it among the works in German that, since the previous decades, had sought to associate the territory’s historical past with fictional elements.

The favourable reception of van der Velde’s works in France led to their publication in collections used for teaching German in schools. One of the novels used for this purpose was Die Gesandtschaftsreise nach China. In 1829, it was translated under the title L’ambassade en Chine, traduit de l’Allemand et suivi d’un Vocabulaire allemand-français a l’usage des écoles and, in the same year, it was inserted in the Leçons de Littérature Allemande: nouveau choix de morceaux en prose et en vers, extraits des meilleurs auteurs allemands a l’usage des écoles de France et des personnes qui étudient la langue allemand, edited by C. F. Ermeler. Ermeler was a French school teacher and, in creating this book, he sought to ‘offer students a collection that could serve as a guide and prepare them […] for the knowledge of a literature as beautiful as it is rich in masterpieces’ .18J’ai dû m’imposer la tâche d’offrir aux élèves un recueil qui pût leur servir de guide et les préparer […] à la connaissance d’une littérature aussi belle que riche en chefs-d’oeuvre’ . Therefore, he made the effort ‘to bring together within a narrow framework a series of pieces from the major German classics, of general interest and, as far as possible, suitable to the taste of the French nation’ .19‘Réunir dans un cadre étroit une suite de morceaux extraits des principaux classiques allemands, d’un intérêt génèral et, autant que possible, du goût de la nation française’ . Among the authors selected by Ermeler are Gotthold Lessing, Friedrich Adolf Krummacher, Christoph Martin Wieland, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué and Johann Gottfried Herder. The 1829 edition also contains eight chapters of van der Velde’s Die Gesandtschaftsreise nach China, which indicates that in France, as well as in England, the works of this author were understood as good examples of German literature.

Ermeler’s work seems to have been quite successful among the public and, a few years later, it started circulating in countries on the other side of the Atlantic, such as Brazil. In 1839, this book was mentioned in an advertisement published in Jornal do Comércio by the bookshop of the Laemmert brothers, which intended to reach

the people who sought the books necessary for the study of the German language, now so cultivated in Europe and taught in all the lyceums and colleges of France, in order to put the studious youth in a position to read in the original the literary texts, today worthily appreciated, of that language. 20‘As pessoas que procurárão os livros necessário para o estudo da língua allemã, agora tão cultivada na Europa e ensinada em todos os lyceos e collegios da França, para por a mocidade estudiosa em estado de ler em original os therouros litterarios, hoje dignamente apreciados, daquella lingua’.

The German language started to be taught in Brazilian public schools in 1840 (see ), which could justify the public interest in Ermeler’s works.

In this context, the brothers Eduard and Heinrich Laemmert played an important role. Both were born in Rosenberg (Baden) and went to Brazil in the first half of the nineteenth century. Together they founded a very successful typography, where they printed books and some periodicals. In 1852, they started publishing a women’s newspaper entitled Novo Correio de Modas, which had the purpose of bringing to the female public content about fashion, literature and culture. In this newspaper, information about German literature was frequently published, as well as some translations of narratives by German-speaking authors, such as E. T. A. Hoffmann, Heinrich Heine and Joseph Christian von Zedlitz.

By this time, van der Velde’s novels were already circulating in Brazil in their original German versions. The Brazilian imperial library, owned by the family of emperors Pedro I and Pedro II in the nineteenth century, contained twenty-three editions of his novels, all of them published in German by the Arnoldischen Buchhandlung in Dresden (see ). He is the most prominent author in this collection, alongside others who also wrote historical novels, such as Walter Scott, Maria Edgeworth and Caroline Pichler. Between 1837 and 1847, two Portuguese translations of the novels Die Gesandtschaftreise nach China (entitled Embaixada a China) and Prinz Friedrich (entitled Theodoro, romance histórico) were published in Lisbon. They soon arrived in Brazil and were also available to Brazilian readers through bookshops and public libraries, such as the Gabinete Português de Leitura do Rio de Janeiro (see ) and Biblioteca Fluminense (see ).

In the second half of 1852, a translation of van der Velde’s novel Der Flibustier into Portuguese, entitled O Flibusteiro ou o Pirata das Antilhas, was published over five editions of Novo Correio de Modas. The first part of the narrative was accompanied by a preface in which the editors explained their choice to publish it:

German literature, still little known among us, offers, nevertheless, such an abundant choice of appreciable novels, that we thought we would give a new proof to our kind readers of how much we wish to please them by publishing the translation of one of the best novels whose author has gained an extraordinary reputation in Germany for his literary works, in which there is the noblest sentiments of a human heart. 21‘A literatura alemã, ainda pouco conhecida entre nós, oferece contudo uma escolha tão abundante de novelas apreciáveis, que julgamos dar uma nova prova aos nossos benévolos leitores e leitoras de quanto queremos agradar-lhes, publicando a tradução de um dos melhores romances cujo autor soube granjear na Alemanha uma reputação extraordinária por suas publicações beletrísticas, nas quais há os sentimentos mais nobres de um coração humano’ .

This text is an indication that in Brazil, as well as in other countries such as France and England, van der Velde’s novels were understood as a good example of German literature and valued for their description of human feelings. The Laemmert brothers, like the French and English editors, probably had access to the reviews published in other countries, which allowed them to know about the favourable reception van der Velde’s novel had received.

By the time this translation was published, the novel Der Flibustier had already been circulating in Spanish for some years. In 1833, an edition entitled El Pirata generoso: Novela Americana was published in Valencia. In the preface, the editors explained that they chose to publish this narrative due to the success it had achieved in other countries:

The public, who are justifiably appreciative of all that they find worthy to instruct and please them, have already formed a very favourable opinion of the works of Monsieur C. F. van der Velde; once they are translated from German into other languages, they have a prodigious dispatch. 22‘El Publico, justo apreciador de todo cuanto halla digno de instruirle y agradarle, tiene ya formada opinion muy ventajosa de las obras de monsieur C. F. van der Velde; así que traducidas del aleman á otros idiomas, tienen un despacho prodigioso’ .

They also mentioned the presence of this novel in private libraries and its appeal to a female audience: ‘his novels […] are to be found in the libraries of people of taste, and particularly in the cabinets of ladies who, combining the instructive with the pleasant, like to amuse themselves with this kind of work’23‘Sus novelas […] se hallan en las bibliotecas de las personas de gusto, y particularmente, en los gabinetes de las damas que, reuniendo lo instructivo á lo agradable, gustan de distraerse con esta clase de obras’ . . They also praised the writer who knew how to describe the facts

with such vivid colours, softening his subject with such dramatic, terrible or tender scenes, that we would not hesitate to award him a prize in the matter, for his pen has triumphed over many obstacles, and has succeeded in making his reading interesting. 24‘Ha sabido hacerlo con tan vivos colores, amenizando su asunto con escenas tan dramáticas, terribles ó tiernas, que no dudaríamos adjudicarle la palma en la materia, pues que ha triunfado su pluma de muchos escollos, logrando interesar en su lectura’ .

The association between the reading of novels and a female audience was quite common in the nineteenth century (see ), and the idea that van der Velde’s narratives would be instructive for women may explain both this Spanish translation and its publication in a women’s newspaper in Brazil. Another relevant aspect of this review is the mention of the novel’s good descriptions, construction of scenes and ability to entertain the reader. All these elements had already been mentioned in critical texts published in the United Kingdom, France and in the periodicals of Leipzig and Jena in previous years, which indicates not only a circulation of the same books between different places, but also the use of similar criteria to evaluate them.

There are also some differences between the examples mentioned. In Brazil and Spain, there were clearer associations between the reading of historical novels and the education of the female public. In the United Kingdom, more comparisons were made between van der Velde and Walter Scott, and in France van der Velde’s narratives served as the basis for dramas and educational books. Still, many of the reviews praised the author’s light style, the construction of the characters and plot, the morality of his narratives and the adept combination of historical facts and fictional elements. This indicates that similar criteria were used in different parts of the world in the nineteenth century, contributing to the formation of a community of readers and the circulation of historical novels produced in the German-speaking territory.

Therefore, studies on the circulation and reception of historical novels such as those produced by van der Velde are able to bring information about the evaluation of novels in the nineteenth century, shedding light on the change in the value of certain literary genres over time. After all, although Carl Franz van der Velde has not received much subsequent attention in the Histories of German Literature, his books circulated broadly in the first half of the nineteenth century and were able to unite readers from different parts of the world. This opens a discussion about the formation of the canon of German literature, which does not contain only the works that circulated to the greatest extent among readers or were positively received by critics. The classification of a book as a classic or part of a literary canon is not necessarily related to the quality of the work or the author, but rather to the cultural and political context that resutled in this categorisation (see ). In the German speaking territory, for example, some authors of the 1800s gained the status of classics mostly because there was a national political interest in them a few decades later .

This process was not only experienced in German-speaking territory. According to Daniel Fulda , before 1800 the need for a nation to have its ‘own classics’ arose much more from the idea of competition between modern nations, which was fundamental to the culture and scholarship of the early modern period. Anne-Marie Thiesse came to a similar conclusion when she affirmed that there is nothing more international than the formation of national identities. Among the important elements in this formation was literature, through which language, cultural aspects and national myths were established . Even in countries far from Europe, such as Brazil, constant efforts were made in the nineteenth century to form the national literary canon and to establish the identity of the newly independent nation (see ). The authors considered most promising were supported by the emperor himself or by public establishments such as the Brazilian Historical and Geographical Institute . In this process, European works were constantly considered as exemplary models of morality and style, such as the previously mentioned novels written by van der Velde.

These books arrived in Brazil through the transatlantic circulation of novels available on the international book market , which made it possible to transport works printed in various languages, such as German, to the country. As there was an interest in German classics emanating from these market from the 1760s onwards, European publishers began to use the term ‘classical writer’ or ‘German classic’ to attract buyers, and these editions were successful because the public recognised them as such . As a result, several books containing works by authors considered to be among the classics—such as Christoph Martin Wieland, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe—were printed in the German-speaking territory and then circulated in the international market.

When some of these works and collections arrived in Brazil, their translated versions were often used in schools or in domestic education, as is the case with Contos do Cônego Christoph Schmid [Erzählungen von Christoph von Schmid]—which had 652 copies acquired by the Rio de Janeiro government in the 1860s in order to be used in Rio de Janeiro school classes (see )—and with the aforementioned book by C. F. Ermeler, used both by students and in the education of the Brazilian Emperor Pedro II (see ). Additionally, in the first half of the nineteenth century, Lessing’s name was mentioned in the Brazilian newspaper Jornal de Debates, in an article that credited him for ‘reviving the German spirit’, which had also produced Goethe and Schiller . Books by Heinrich Heine, August von Kotzebue, Goethe and Schiller books—usually included in selections of the German classics—were also available to Brazilian readers, either in the original language or in French and Portuguese translations, in the bookshops of famous publishers of the period, such as the Laemmert brothers and Baptiste-Louis Garnier (see ; ; ).

This data, when analysed in conjunction with the information on the wide circulation of van der Velde’s historical novels, indicates that in the book market of the nineteenth century, there was space both for editions of books considered worthy of being placed among the classics of a nation’s literature and for authors who achieved success with their readers, but whose works would not be considered exemplary of a country’s literature. For this second group of authors, there is little space left in Literary Histories, and their books are rarely read or published anymore. Even so, the reconstruction of their circulation and reception during this time can reveal information about the connections enabled by the nineteenth century book market, which allowed novels written by German-speaking authors to be republished in multiple editions and reach readers on the other side of the Atlantic.