Abstract

In the Afro-Eurasian core, from Egypt to China, writing emerged, developed, and was then transferred to the periphery, for instance, to the German-speaking world and to Japan. This process loosely synchronised the politics and literature of these two cultures, thereby explaining the striking similarity between song anthologies compiled in both regions, at a time when the two cultures had no direct interaction and also differed greatly. The similarities and the differences between the two cultures were presented by describing the networks that consisted of different factors such as power, gender, and media, and in which the songs circulated.

Introduction

Aim of the study

Songs are born, spread orally, and passed down through manuscripts until texts are evaluated, selected, and recorded in anthologies. These texts may be given the status of a canon to ensure, with the help of this authority, that songs continue to circulate even further into the future and in the future. These processes of the circulation of songs in society and in time were common to the German-speaking world and Japan, which suggests a comparison.

The aim of this case study is to compare old German and Japanese song anthologies, describing the networks in which the songs circulated and which consisted of different factors, such as power, gender, and media.

Objects of analysis

We can make this comparison because of the overlap in the ages in which famous anthologies of German-language Lieder (songs) and of canon-forming anthologies of Japanese-language 和歌 (waka, ‘Japanese songs’, often translated as ‘court poetry’, with a dual meaning of written poetry and vocalised song) were produced. From the German-speaking world, we refer to the Kleine Heidelberger Liederhandschift (Small Heidelberg Song Manuscript, c. 1270), the Weingartner Liederhandschrift (Weingarten Song Manuscript, c. 1310–1320), and Codex Manesse (also called the Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift [Large Heidelberg Song Manuscript], c. 1300–1340) and from Japan, to the twenty-one anthologies (905?–1439), compiled by decrees of 天皇 (tennō, ‘emperors’), of which the 新古今和歌集 (Shin kokin waka shū, also Shinkokinshū, 1205, English translation: ) represents one of the apexes.

Methods of analysis

The discipline of Comparative Literature, which emerged in nineteenth-century Europe, offered a simple model for comparing literatures in different languages with each other. It typically analysed receptions and influences of literary works. Because of its simplicity, this model was widely applied. It was also a popular model for analysing the way literature from Europe and the USA was exported, translated, and received as a model elsewhere in the world in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This also led to the spread of this science, Comparative Literature, along with Western literature around the world.

Comparative Literature is, therefore, good at comparing post-nineteenth-century literature and analysing its translation and reception. It is, however, ineffective in comparing pre-nineteenth-century literatures without the relationships through translation or reception, for example, when comparing medieval European literature with Japanese literature of the same period. At that time, unlike today, there was no translation of European literature into Japanese, nor was there any influence of Japanese literature on European literary works. There is a striking resemblance between European literature of the Middle Ages and Japanese literature of the same period, for example, in the fact that each had its own anthology of courtly poetry; however, the method of comparison must be sought elsewhere than in Comparative Literature.

This is where Global History can help. Global History, as a branch of historiography, allows us to trace globalisation even further back than the nineteenth century, and even to consider the cultures of the European continent and the Japanese archipelago around the year 1000 AD as having emerged from a common root. Global History has given rise to the view that civilization’s development in the Afro-Eurasian core, from Egypt to China, extended to eastern and western peripheries, such as Europe and Japan, so that peripheral cultures became similar.

Historians J. R. McNeill and William H. McNeill provide ‘A Bird’s-Eye View of World History’ (the subtitle of their book), including the period from 1000 to 1500 CE . They observe the increasingly intense interactions between the economic, political, religious, and cultural centres of Eurasia, and the growing density of networks they call “webs”. They also recognise striking parallels between the development of the two peripheries of Eurasia, Western Europe, and Japan: the development of the two areas was loosely synchronised, as each was influenced in similar ways by the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires on the one hand and China on the other—both areas, whose development was, in turn, loosely synchronised. To focus on writing, the medium of both politics and literature, written cultures developed in vernacular languages not only in Western Europe but also in Japan: German, for example, competed with Latin culture, which in turn competed with Byzantine culture through Greek; Japanese was influenced by Chinese culture and, at the same time, sought to become independent. Thus, the German-speaking world and Japan were comparable in developing their written cultures. McNeill and McNeill write:

Parallels between the Atlantic and Pacific flanks [of Eurasia] are striking. On both, multiple ethnic groups participated, and the advance of literacy in local languages strengthened local states and reinforced ethnic and cultural autonomy. Japanese “feudalism” resembled the feudalism of medieval Europe […].

Both regions, Europe and Japan, have a long tradition of writing. Both regions wrote not only in the lingua franca (Latin and Chinese) but also in the vernacular. The way in which writing underpinned politics and culture was similar in both regions where there were no direct contacts. This is a striking example of the ‘strange parallels’1The expression comes from historian Victor B. Lieberman, who discusses these parallels between the history of Southeast Asia and that of Europe. found at both peripheries of the Eurasian continent, but Global History suggests that these parallels are not accidental. This is why this article compares literature from the perspective of writing, and why politics is discussed alongside the analysis of literature.

Discussing politics together with literature and looking at them from the perspective of writing is also supported by methods other than Global History. Michel Foucault analysed the discourses in terms of the political, social, and cultural contexts in which they operate (for example, ). This method is called discourse analysis. Friedrich Kittler applied this to develop the method of media analysis, which analyses literary and academic discourses in terms of their media context (for example, ). Both Foucault and Kittler focussed on European culture, but their methods can also be applied to cultural comparisons, for example, between European and Japanese literature ( and ).

Comparison of courtly literatures from Europe and Japan has interested some researchers from the perspectives of rhetoric , the novel as a genre , love as a subject , or materials for narratives . A comparison of Italian and Japanese poetry has also been undertaken . Our attempt differs from previous research in that we combine the methods of global history, discourse analysis, and media analysis, choosing German and Japanese anthologies as objects of comparison.

The analysis of a relationship of influence within a cultural area (for example, Goethe’s reception of Shakespeare within Europe) forms the basis of comparative literary studies. The means by which famous works by prominent authors spread globally can also be one of the topics of this science (for example, how Shakespeare’s works were translated into different languages and performed on multiple continents). However, we suggest another possibility for a global comparative literature: comparing literature from distant areas that had no direct contact with each other, but whose historical trajectories were loosely synchronised—a field of study that can only be opened up with the help of Global History.

Structure of discussions

We begin our comparative study like McNeill’s in 1000 and end in 1340, when the editing of Codex Manesse was approximately complete. During this period in the German-speaking world and in Japan, literacy strengthened politics and literature. Writing in politics and writing in literature were closely related: in this study, we will look at the relationship of writing to that of politics, individual songs, and poetry collections in turn. Writing has various relations with image, orality, gender, power, and the materiality of the writing surface. When we discuss writing, we will discuss it in relation to this list.

In the following, the same questions posed by Nawata, who wrote this introduction, are answered by Terada in relation to the German-speaking world and by Yoshino in relation to Japan.

Writing and politics

Was politics conducted in writing, or was the voice the more important authority? How does the relationship between the lingua franca and the vernacular concern the relationship between voice and writing in politics?

The German-speaking area

Clearly, in the German-speaking world from 1000 to 1340, documents were prevalent to a certain extent in governance and administration. Important documents concerning rulership and rights were written in Latin on parchment, and over time, more and more documents were preserved. Although at that time, society attached great importance to writings on parchment, it did not regard them as the sole authority, however. Oral communication had been of great importance since ancient times and remained so.

Indeed, decrees were often proclaimed orally. When a decree was issued, a large number of people were present to ensure that the decree was widely disseminated, but they also acted as witnesses when necessary. A description of the Sachsenspiegel, the first law written in German (1220–1230), gives indirect insight into the historical context.2 ‘Wo man mit sieben Mann zeugen soll, da darf man einundzwanzig Mann wegen des Zeugnisses befragen’.

Japan

From the Heian period (end of the eighth–end of the twelfth century) onwards, orders from ministries and agencies were issued in the form of official documents called 宣旨 (senji), suggesting that from 1000 to 1340, politics in Japan was mainly conducted through writing. However, since the emperor’s or the emperor emeritus’s imperial orders were formally communicated orally by secretaries and were also documented (these documents were called 口宣 (kuzen)), the “voice” of the ruler’s body was crucially valued ( and ).

Men wrote all official documents in Chinese script—Chinese was the lingua franca of East Asia at the time—the characters of which were called 真名 (mana, meaning ‘formal characters’). In contrast, characters peculiar to the Japanese language were called 仮名 (kana, ‘provisional characters’) or 女手 (onnade, ‘female characters’). Kana, created by writing Chinese characters in a broken form, was considered a script that could be used in daily life and also by women.

If politics was conducted in writing, what was the writing surface?

The German-speaking area

Until the end of the thirteenth century, most official documents in the German-speaking world were produced on parchment. In Italy, where commerce was flourishing and where many people had learned to read, write, and calculate, the use of paper began early; whereas in German speaking area, it did not become widespread until the fourteenth century . The oldest surviving paper document was produced in the office of Emperor Frederick II (1194–1250), but its durability was inferior to that of parchment, so that in 1231, the Emperor himself ordered that important documents should be preserved on parchment. Parchment’s superior durability was of great importance for certificates, which had to be of permanent validity, and its luxurious appearance was also significant.

Japan

In the second century BCE, the art of papermaking originated in China, and in the sixth century, it was introduced to Japan . Paper produced in Japan has remained the country’s dominant writing surface to this day, not only because it is light and easy to handle, but also because of its excellent preservation qualities. Political documents written from 1000 to 1340 were naturally written on paper.

Who were the people in power: women or men? Were they literate or not?

The German-speaking area

In both secular and ecclesiastical societies, men held power. Only within a convent, of course, did women hold power. Until the end of the thirteenth century, secular society basically did not require those in power to be literate; if necessary, clerks in secretariats could read and write for them.

Japan

Although in ancient times, women also held the throne, all emperors from 1000 to 1340 were male, and many of them ascended to the throne as infants. Until the latter eleventh century, the emperor’s maternal relatives held the real power, assisting the child emperor and conducting the political system. This was followed by a brief period of direct rule by the emperor (1068–1072), after which emeritus emperors took the reins of government. However, this political regime came to an end in 1221, and from then on, the Warrior Government (鎌倉幕府, Kamakura Bakufu) established in East Japan effectively took control. Yet, the structure was headed by a shogun appointed by the imperial court, and the emperor was the formal head of Japan. All those in power were literate.

Writing and songs

Were songs sung orally? Or were they written? Or both?

The German-speaking area

In court culture, the role of song was to entertain and amuse the audience. Sometimes, the audience would sing along; sometimes, they would even dance. Thus, we can safely assume that the first step was to sing orally. At some point, however, the text of the song began to be recorded.

Japan

In the period 1000–1340, a waka was composed both in everyday life and in public, and was often recited as well as written. At public poetry gatherings, a person called 講師 (kōji) would recite waka poems an author had written on paper called 懐紙 (kaishi). In everyday life, too, it was common to hum old wakas. Stories and poetry anthologies often contain scenes of people humming old wakas.

If a song was written, on what writing surface was it written? What relationship did the character of the writing surface have to the song?

The German-speaking area

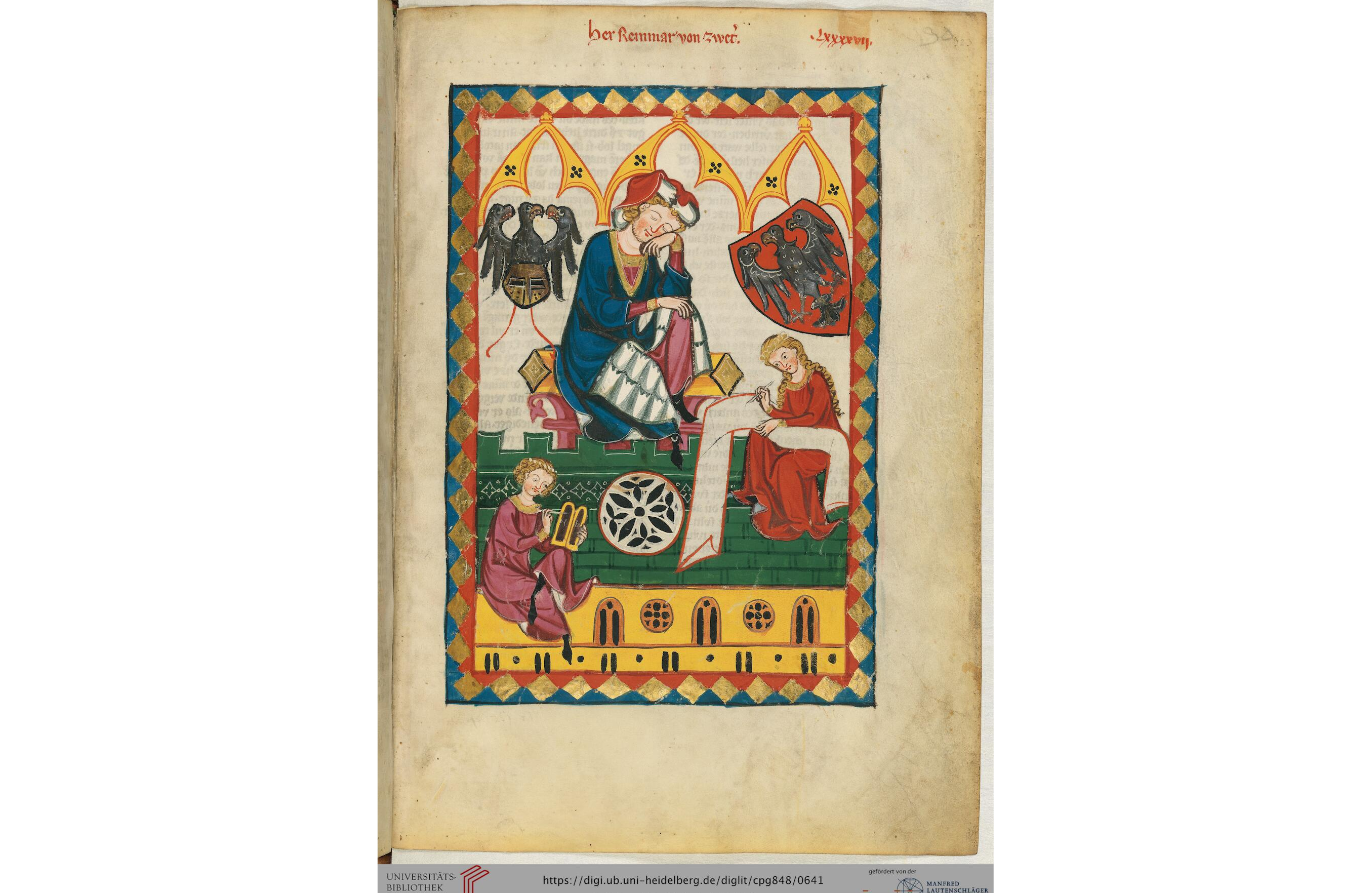

The means of writing must have been wax tablets and styli. However, this stage of recording was ‘more for use than for preservation’ . In fact, the Large Heidelberg Song Manuscript contains illustrations of writing on wax tablets. Despite a lack of proof, as the poet’s fame grew, he probably moved gradually from one-time use of wax tablets to parchment for preservation over time (parchment was so valuable that it was frequently reused). Indeed, illustrations in the Large Heidelberg Song Manuscript often include scrolls—partially by a woman (the illustration of Reinmar von Zweter).

Japan

Wakas were written in 墨 (sumi, ‘ink’), with a 筆 (fude, ‘brush’) on paper. Paper was made in different ways and in different thicknesses and sizes, using different raw materials. Paper decoration was also highly developed and varied according to use. The quality of the paper was often proportional to the quality of the book. Because paper was so valuable, it was frequently recycled and reused.

Who were the people who sang or wrote the songs—a person in power or someone who served the political system as a scribe? Were they women or men, or both, and if both, did they exchange songs?

The German-speaking area

In common entertainment, the itinerant entertainer, called Spielfrau (‘play woman’ or ‘female performer’) or Spielmann (‘play man’ or ‘male performer’), sang. They performed songs, dances, and other entertainments at court. Some sang songs not only in praise of the sovereign who had invited them but also in disparagement of those who opposed him. Even Walther von der Vogelweide, one of the most famous lyric poets, confessed at the end of one of his works: ‘I have been so abusive that my breath stinks’.

All of the poets whose names have been passed down to us are male, and many of them were knights. Some works were handed down in the name of emperors or kings.

Japan

As the two prefaces to the 古今和歌集 (Kokin waka shū, also Kokinshū, 905 (?), English translation: ), the first imperial collection of waka poems from the early tenth century, state that everyone (even animals) can compose waka, but the first to compose waka were gods. From the tenth to the fourteenth century, imperial anthologies of waka were the official centre of culture and included wakas of gods and Buddhas (!), emperors, empresses, ministers, officials, court ladies, priests, female entertainers, and unknown authors.

When songs were written, were they accompanied by images?

The German-speaking area

The German-speaking area produced only two illustrated complete song anthologies, the Large Heidelberg Song Manuscript and the Weingarten Song Manuscript. Sometimes, portraits in the same pose (for example, Walther von der Vogelweide), are included in both the Large Heidelberg and Weingarten Song Manuscripts, so they must have had a common source. If so, then some images already existed in the early days of song manuscripts .

The Manesse family’s intention in including illustrations in the Large Heidelberg Song Manuscript was to increase the value of the codex as a work of art. Possession of such an object served to display their wealth and power.

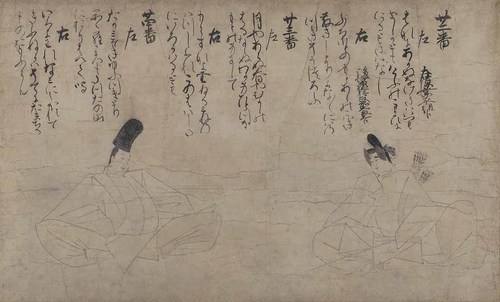

Japan

Basically, waka poems were not accompanied by illustrations. However, portraits of poets might have been included from the beginning in the thirteenth-century collection of wakas titled 時代不同歌合 (Jidai fudō uta awase), compiled by the Emeritus Emperor 後鳥羽院 (Gotoba-in, 1180–1239). This collection is of representative wakas by poets up to the previous generation. Honouring them was a possible reason for the anthology to include portraits.

Writing and song anthologies

In poetry anthologies, songs are not voiced, but written. What is the character of the voice—which may have been more or less present when each song was composed—considered in poetry anthologies? Were they conceived as a device to reproduce the original voice?

The German-speaking area

Manuscripts of epic poems were generally used for readings. They might have been read to large audiences in castle halls or by one person to a small group around a table. Naturally, we assume that manuscripts of lyric poetry were also used for recitation.

Not only in the German-speaking world, but also in Europe during the Middle Ages, songs were probably not only recited but also sung. From antiquity to the Middle Ages, manuscripts with musical notes (neuma) were preserved. In the German-speaking world, however, such manuscripts are few; the oldest Carmina Burana dates from around 1230. It is a collection of mostly Latin songs, with a few German lyric poems with musical notes.

Japan

The poetry anthology was probably not conceived as a device for reproducing the voice. Rather, as early as the tenth century, there were attempts to arrange wakas visually, in a grid pattern, for example (源 順 (Minamoto no Shitagō, 911–983): 順集 (Shitagō-shū)).

Whether poetry collections were generally read aloud or not is not known. However, I do know that four or five wakas from the beginning of the New Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern (1205) were recited aloud at a banquet to celebrate the completion of this anthology.

How did the nature and form of writing surfaces (loose paper or loose parchment, scrolls, books) affect compilation? In what forms of object did the compilation result?

The German-speaking area

To date, three complete manuscripts of lyric poetry have been preserved from the period. The oldest, the Small Heidelberg Song Manuscript, was completed around 1270, about a hundred years later than the oldest manuscripts containing epics. Lyric poems, which were probably oral when created, took that long to appear in the oldest surviving manuscripts, as opposed to epics, which were conceived and written from the outset as literary works or were translated mainly from French.

Translating the lyric into written form did not begin with the Small Heidelberg Song Manuscript. In fact, a number of manuscripts are thought to have been written earlier. However, these testimonies are all fragments or writings in the margin of older manuscripts—each containing only one or a few works. Writing lyric poetry on parchment manuscripts is regarded as a rather accidental, sporadic, unsystematic, and marginal phenomenon.

So how were lyric poems written? Presumably scrolls, individual parchments, and wax tablets were used, but none survive from before 1270. Franz-Josef Holznagel speculates that the absence of any evidence from the first half of the thirteenth century might be due to the ‘one-off’ or ‘ephemeral’ nature of writing lyric poetry .

Finally, from about 1275 to the beginning of the fourteenth century, more and more German lyric manuscripts were produced. The possible reasons lyric poetry appeared in manuscripts much later than epic poetry are as follows.

– Lyric poetry was restricted to oral performance, whereas epic poetry was conceived and produced in written form from the outset. Lyric poetry also had a firm place in court culture, but the desire to write down and preserve the work appeared much later than that for epic poetry .

– Production of lyric manuscripts was in itself a challenge. Even for the Small Heidelberg Song Manuscript, collecting works of thirty poets and having them written down would have been impossible unless the person who sponsored the work had not only a keen interest but also a fierce desire to collect. There were few such people.

Japan

For the New Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern, the eighth imperial anthology of waka poems, we know details of compilation from the diary 明月記 (Meigetsuki, 1180–1235) kept by 藤原 定家 (Fujiwara no Teika, 1162–1241), one of the anthology’s editors. He wrote that a 和歌所 (wakadokoro) or a Place of Waka (in the meaning of ‘Department compiling the Imperial Anthology of wakas’) was arranged in the Imperial Palace for editing the anthology. Not only the editors, but also Gotoba-in himself, who ordered the compilation, was involved in almost all of the editing work. In the Place of Waka, the editors selected from the vast number of wakas collected, and arranged them into categories. Since the editors sometimes added excellent wakas composed at frequent poetry gatherings held at the Place of Waka, it is likely that they began the compilation process on separate sheets of paper, and when they had made some progress in classifying and arranging the wakas, they compiled them into scrolls.

Who were the compilers? Were they persons in power or scribes who served the political system? Were they women or men?

The German-speaking area

In medieval Germany, the actual state of compilation is difficult to ascertain. No extant historical documents specify who compiled the manuscripts. No doubt, however, the sponsors’ intentions and tastes were taken into account.

In the Large Heidelberg Song Manuscript, the poet Hadlaub mentions in his work that a father and son of the noble Manesse family of Zurich ‘collected more songs in their songbooks than anywhere else in the kingdom’. No further details are provided. The manuscript’s writing is estimated to have begun around 1300, but the collection of sources for it is thought to have begun, at the latest, in the 1290s. That the manuscript was finally completed (or, more accurately, that work on it ceased) around 1340 suggests that some guidelines were established at the beginning and that the manuscript continued to be written according to them .

Women were not only active as scribes. The literacy of women in court society was often higher than that of men. Given the fact that they even produced manuscripts, it is quite conceivable that women were also compilers. The works of Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179) and Mechthild von Magdeburg (c. 1207–c.1282) were transcribed, at least in the early stages, in the convents for women where they were. The compilation and revision of texts would also have been carried out there.

Japan

For imperial waka anthologies, there were no female compilers (editors). As compilers, then, not only leading poets were chosen, but also those poets who enjoyed strong relationships with the emperor who had commissioned the anthology’s compilation. In a few cases, the emperor himself was a compiler, for instance Emperor Emeritus 花山院 (Kazan-in) was a compiler of the early eleventh-century anthology 拾遺和歌集 (Shūi wakashū or Collection of Gleaning of Japanese Poems, this English translation of the title is taken from ).

In a private collection of waka poems by a single poet, 私家集 (shikashū), the poet may have compiled the collection him/herself, or it might have been compiled later by others. For example, 建礼門院右京大夫集 (Kenreimon-in Ukyōnodaibu shū, English translation: ), a collection of waka poems from the thirteenth century of the Kamakura period (1185–1333) by the courtly lady Kenreimon-in Ukyōnodaibu has several different versions, one of which shows how the author’s own handwriting was copied by a female friend and then by another woman. Clearly, women sometimes compiled private collections.

Were the poetry anthologies that were compiled accompanied by images?

The German-speaking area

Manuscripts with images, not just portraits, had been common in Europe since ancient times. The number of decorated manuscripts, however, did not increase until the late Middle Ages, and in manuscripts of literary works before 1300, the decoration was mainly initials. In the Song Manuscripts, the Small Heidelberg Song Manuscript does not include a portrait of the poet, whereas the Weingarten and the Large Heidelberg Song Manuscripts include a full-page portrait of the poet.

We cannot know why they did or did not include images, but we can guess. First, as mentioned above, documents were mainly concerned with property, income, and rulership. Parchment itself was very expensive, and the number of literate people was limited. Having literary manuscripts written and illustrated was, therefore, a luxury. With a song collection, one could flaunt one’s wealth. Probably, this was the Manesse family’s intention when they commissioned the Large Heidelberg Song Manuscript.

Japan

Imperial waka anthologies and private waka collections were not usually accompanied by images. However, the paper on which the wakas are copied is sometimes decorated with pictures of flowers and birds, and when the wakas were printed in later periods, illustrations were sometimes included with the wakas.

Does compilation involve some methodological consciousness? Is there any germ of philology in it?

The German-speaking area

All surviving manuscripts are presumed to have been copied from earlier ones, occasionally with some modification, but because no single source has survived, the following is hypothetical. In the Small Heidelberg Song Manuscript, the language’s inconsistency suggests more than one original source. In the latter thirteenth century, there were likely already collections of songs by famous poets such as Walther von der Vogelweide and Reinmar. However, these manuscripts had different compilers, who collected songs according to different ideas. The same author’s works were transcribed in different dialects. Some authors’ names were transmitted differently, and the works’ arrangements also changed. Possibly also, the transcriber changed the same work’s internal arrangement (the order of the strophes). Compilers of the Small Heidelberg Song Manuscript did not care about these differences and left many inconsistencies. Precisely for this reason, however, the sources remain more visible. The paucity of such inconsistencies in the Large Heidelberg Song Manuscript is indirect evidence that the compilers carefully studied preceding manuscripts (of which there must have been several) and copied them with as few inconsistencies and contradictions as possible.

Japan

The New Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern, an imperial collection of waka poems compiled at the beginning of the thirteenth century, is known in detail through Meigetsuki, the above-mentioned diary of one of its compilers, Fujiwara no Teika, who describes the process of compilation and the correspondence about the wakas’ arrangement.

In addition, 袋草紙 (Fukuro zōshi or Book of Folded Pages, this English translation of the title is taken from ), a book on waka poetry written by 藤原 清輔 (Fujiwara no Kiyosuke, 1104–1177) from the twelfth century, contains sections detailing rules for compiling imperial waka anthologies and also various circumstances surrounding each previous anthology’s compilation. Kiyosuke’s father, 藤原 顕輔 (Fujiwara no Akisuke, 1090–1155), was a compiler of the sixth imperial waka anthology 詞花和歌集 (Shika waka shū or Collection of Verbal Flowers of Japanese Poems, 1151, this English translation of the title is taken from ), and Kiyosuke assisted his father in the work. As a member of the 六条家 (Rokujō family), which had a long line of poets and imperial compilers, Kiyosuke recorded some facts about imperial collections in preparation for his future career as an imperial waka anthology compiler. This can be called the germ of philology.

Also worth mentioning is how poetry anthologies were copied. Not until the Heian period’s end in the latter twelfth century, around the same time as Fukurozōshi, did poetry anthologies begin to be strictly copied. Until then, private collections and even imperial waka poetry anthologies were not copied with strict accuracy, and large discrepancies have been noted between surviving copies. That there are examples today in which the precious originals have been copied exactly as they were written, without a single mistake, is due to the emergence of the concept of 歌道 (kadō, ‘the art of waka poetry’) and the professionals who were responsible for it (such as the 御子左家 (Mikohidari family), to whom Teika belonged, and its rival, the Rokujō family) .

Conclusion

In the Afro-Eurasian core, writing emerged, developed, and then was transferred to the periphery, for instance, to the German-speaking world and to Japan. This process loosely synchronised these two cultures’ politics and literature, thus explaining the striking similarity between song anthologies compiled in both regions, at a time when the two cultures had no direct interaction and differed greatly.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the research project “Towards a Global History of Culture” as part of the Chuo Research Institute Symposium Series. The Japanese version appeared as .